This article originally appeared in the Line.

By Kaveh Shahrooz, October 5, 2022

Revolutions are funny things. They sometimes appear impossible until, in one single moment, they become inevitable. In Iran, that moment came on September 13th with the murder of a young woman.

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old who was also known by her Kurdish name “Gina,” had come from Iran’s Kurdistan region to visit her brother in Tehran. It was during that trip that she faced a particular humiliation that has become a fact of life for tens of millions of women in that country: a run-in with the country’s gasht-e ershad (“Guidance Patrol”). The role of this roving gang, seemingly imported from Atwood’s Gilead and called Iran’s “morality police,” is to monitor the streets to find and punish violations of the regime’s seventh-century moral and dress codes.

Having determined that Mahsa’s hijab exposed a little too much hair — a few strands of a woman’s hair and men will simply be incapable of controlling their sexual urges, the logic goes — they detained and beat her severely. The story for most women who deal with the morality police typically ends there, after which they are released to seethe at having endured another round of state-imposed gender apartheid. For Mahsa, the story ended differently: with a skull fracture that caused her to be brought, brain dead, to a local clinic. She died there on September 16th.

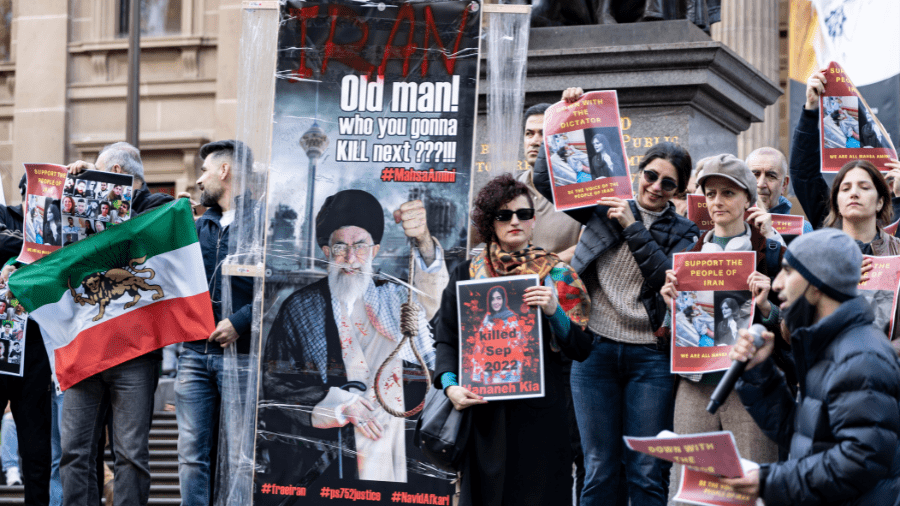

The murder of Mahsa Amini was the spark that set off a revolution. The killing reminded women of their daily misery at the hands of a regime that, both de facto and de jure, treats them as second-class citizens. And it reminded everyone of the million other senseless cruelties, large and small, that they must endure daily at the hands of a barbaric theocracy. Outraged by the death of an innocent young woman, the people took to the streets in protests that continue to this day.

There have been mass protests in Iran before. In 2009, in response to a widespread belief that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had illegally stolen the presidential election — to the extent the word “election” means anything in a country where candidates must first be approved by a clerical body loyal to the regime — citizens protested by the millions. Their slogan, “Where’s my vote?” rested on the premise that a fair, albeit controlled, election was something that could change the system for the better. The protesters typically avoided confrontation with security forces. Even when they happened to corner a regime thug periodically, they ensured that no harm was done to him.

In 2019, mass protests flared again, this time over the abject poverty caused by the regime’s corruption, mismanagement, and foolish pursuit of nuclear weapons at the cost of international isolation. There were no peace signs and no particular kindness to security forces this time, but the protesters still retreated in the face of the security forces. In only a few days, the regime killed 1,500 people and detained and tortured many more. The protests were crushed.

What makes today’s uprising a revolution is twofold: the public’s almost universal willingness to openly confront and fight the security forces in the streets, and the slogans that leave no room for misinterpretation of the protesters’ core demand: “Death to the Dictator” and “Death to the Islamic Republic.” No one is talking about votes and elections anymore.

The regime has responded to this growing revolution in the only way an ogre can: with brutal, indiscriminate violence. On Monday, its security forces surrounded Sharif University — an elite engineering college that is often a feeder school for Harvard, Stanford, and MIT — and arrested dozens of students while shooting live ammunition.

But, in further evidence that this is indeed a revolutionary moment, the attack on Sharif did not quell the student protests. The crackdown on Monday sparked even more university and high-school protests on Tuesday. Fear, the currency by which dictatorships survive, has seemingly disappeared.

To better understand the roots and hopes of this revolution, it is perhaps useful to know two cultural products that have become intertwined with the uprising.

The first is a simple song, recorded on a keyboard by a young musician named Shervin Hajipour in what seems to be his bedroom, and uploaded to YouTube. It is called Baraye (“For” or “Because of”) and sets to a simple melody the text of tweets sent by ordinary people to explain why they are fighting. “For my sister, your sister, our sister,” he declaims in a voice tinged with deep sorrow; “for the right to dance in the alleyway”; “for the shame of poverty”; “for the yearning to just have a normal life.” Hajipour’s singing drives home the revolutionaries’ message: what they yearn for is to end a theocracy that has impoverished them and removed all ordinary joys from their daily lives.

Naturally, within days Hajipour was himself arrested. But the song has touched a raw national nerve and has become the poignant, inescapable soundtrack to the fight for simple dignity.

The second cultural product is the chant that has become central to the revolution. Over and over, the protesters yell “Woman, life, freedom” like a mantra. Adopted from a Kurdish chant, the phrase expresses, in a beautiful simplicity, how these revolutionaries distinguish themselves from their enemy.

Their enemy has had 40 years to implement its dark vision of patriarchy, death, and repression. The people want the precise opposite. They are fighting to get it. And so far, even in the face of extreme violence and danger, they haven’t backed down. This is something new and different. The world should be watching.

Kaveh Shahrooz is a lawyer and a human rights activist. He is a former senior policy adviser on human rights to Global Affairs Canada and is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Centre for Advancing Canada’s Interests Abroad.