By David Snider, February 27, 2023

Perhaps no other country has as much to gain in ensuring safe shipping in polar waters as Canada. There are real human safety and environmental consequences to a weak regime for Arctic shipping, as well as financial costs to responding to them.

There is now an opportunity given the likelihood of increased shipping through polar waters as a result of climate change, declining sea ice, and energy and resource pressures. While there is less multi-year sea ice, Arctic shipping will remain unpredictable, dangerous and difficult for decades and centuries to come. Recognizing this, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) underwent a long process in the 2000s to develop stronger, mandatory guidelines to govern polar shipping. The result was the Polar Code, which came into effect on January 1, 2017.

At the time, it was heralded not only as a huge step forward in managing shipping in high-risk polar waters, but almost as the answer to all the problems that existed due to the numerous and often conflicting national and regional rules, regulations and guidelines that had existed previously. Now, six years later, we can look back and see that the Polar Code was a necessary first step in developing a single, global mandatory set of rules for polar operations. But it was not the fix-all that many had lauded.

To be sure, many of the technical requirements laid out in the Polar Code have remained valid, achievable and, for the most part, enforceable. But in the areas of environment, manning, training and certification, this is not the case. The human resource elements of the Polar Code – the requirements laid out in the Code and amendments in the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) meant to codify Polar Code goals – have not been as effective as hoped.

Application

The Polar Code is “goal based,” allowing for various methodologies of meeting the effective goals required rather than providing specific guidance.

Currently, the Polar Code applies in a mandatory manner only to SOLAS (International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea) vessels greater than 500GT (gross tonnage), leaving out many smaller vessels.

Since initial implementation, this limitation has been partly addressed by new voluntary Guidelines for Fishing Vessels in Polar Waters (February 2023) and Guidelines for Safety Measures for Pleasure Yachts of 300GT and Above Not Engaged in Trade Operating in Polar Waters (May 2021). However, both guidelines are recommendations only.

Training and certification requirements

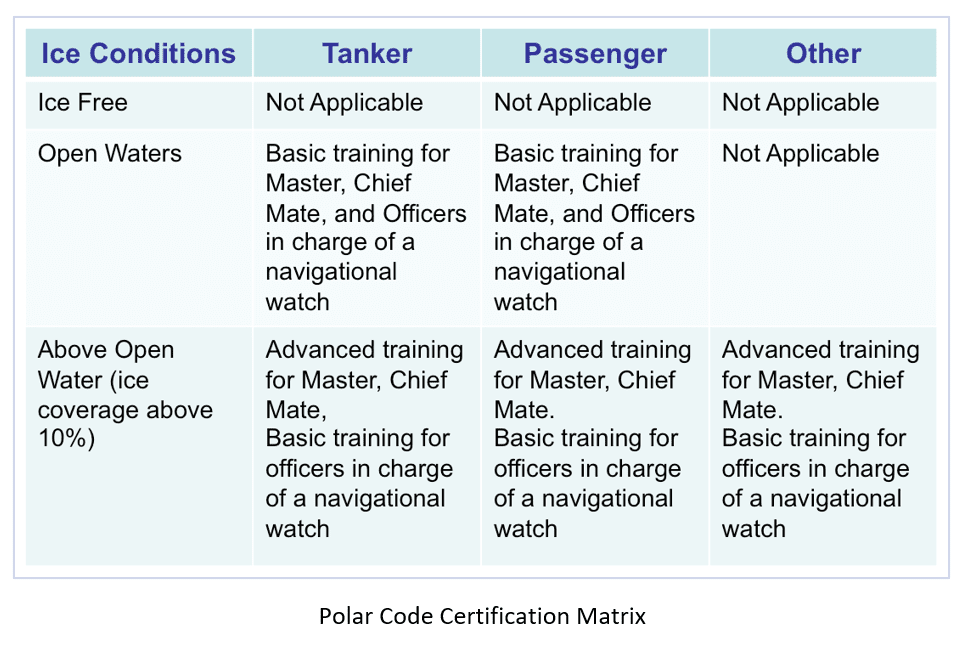

The Polar Code’s Chapter 12, on Manning and Certification, lays out the basic requirements for bridge officers based on the type of ship and extent of sea ice expected to be encountered. The scope is very general in nature, cross referencing either tankers, passenger vessels or “other” vessels against ice conditions described as “ice free” (defined as no ice present), “open waters” (defined as a large area of navigable water in which sea ice is present in concentrations less than one-tenth) or “other waters” (though not clearly defined, it is taken to mean waters with ice concentration one-tenth concentration or greater).

Depending on where a particular ship fits into the matrix, bridge officers may be required to have completed prescribed training and hold flag state issued Certificates of Proficiency (CoP) in either Polar Waters Basic Training or Polar Waters Advanced Training.

To meet the training requirements, IMO produced model courses for both basic and advanced training. These model courses outline specific skills and knowledge that must be addressed in recommended syllabi, and the total training time to be committed to ensure adequate knowledge transfer. Training institutions that would be flag state-approved were expected to meet the model course requirements.

The system is set up so that a bridge officer first attends a one-week Basic Course, upon which he/she would apply for the appropriate flag state-issued CoP (Certificate of Proficiency) Basic. With that in hand the officer is required to obtain a minimum number of days on the bridge of a ship operating in Polar Waters. They then complete a one-week advanced course in order to be issued the CoP Advanced.

One glaring omission in the Polar Code is the lack of requirement for sea-time in ice-covered waters. Bridge officers are being issued CoP Advanced having never actually operated or seen ice.

Not all training is equal

With the implementation of the Polar Code, there was a sudden burst of interest in providing the required training. In very short order a plethora of training courses appeared, advertised as meeting Polar Code requirements. The reality is that not all training is equal. Many of the courses now available are not providing effective training. Courses are being conducted with far fewer training hours than required in the model courses; and course content is developed and presented without sufficient detail or by instructing staff that lack in-depth subject matter knowledge or expertise. Course attendees emerge believing they are adequately prepared for any eventuality in polar waters, when in fact they lack the practical skill and competency required to operate when ice is encountered.

Some training institutions are issuing course certificates that appear to indicate that they “meet Polar Code requirements as approved by…”, leading innocent mariners to believe that they meet the true requirements while ignorant of the reality, blissfully venturing forth.

Practical evidence indicates that ill-trained and inexperienced mariners are being accepted as meeting requirements when, as indicated above, they are not sufficiently trained or experienced. In some cases, even senior officers have been found to not possess the required flag state issued CoP, but merely training certificates issued by whatever training institution they attended. Even some that possess appropriate CoPs have proven themselves well below the competency expectations required for safe ice operations. Lack of full comprehension of the risks or competency operating in or near ice regimes has led to incidents such as ice damage with potential environmental impact.

Enforcement

It is one thing putting in place training and certification requirements, but it is quite another to put in place effective enforcement measures. Bluntly speaking, the enforcement of training and certification has been generally left to ineffective Port State Control inspection, or remote querying of vessels prior to entry into Polar Waters by applicable coastal states.

Port State Control has not been effective in monitoring the qualifications and competency of mariners purportedly meeting polar training and certification requirements. Vessels are departing last ports outside Polar Waters either unaware that they do not meet the requirements or content that they have dodged a bullet, so to speak. Coastal state monitoring prior to entry into national waters has proven more effective. The downside is that coastal state monitoring catches the inadequate training and certification at the last moment, often just before a vessel is intending to enter Polar Waters, delaying or even halting voyages completely.

Filling the gaps

How do we close these gaps? With respect to ice operations competence, the method already exists.

Closing the training and certification gap via IMO may take years to realize. The gap in ice operations knowledge can be adequately met today by owners and insurers requiring officers possess Nautical Institute Ice Navigator Certification. This training and certification scheme complements the Polar Code requirements. Ice Navigator Level 1 and Level 2 parallel Basic and Advanced Polar Water training while adding elements that are designed to ensure the certificate holder meets ice operations competency.

The Nautical Institute, a non-governmental organization with consultative status at the IMO, has approved training institutions whose courses meet the Ice Navigator Training Scheme standards with only slight adjustment from those required to meet Polar Code flag state approval. The Ice Navigator Certification not only places a greater emphasis on academic and theoretical training on specific ice operations competencies while adding effective full mission bridge simulations in ice operations, but it also requires considerable sea time operating in ice-covered waters before an applicant is issued Level 2 Certification.

Owners, insurers, coastal or flag states that wish to augment the more elementary training requirements laid out in the Polar Code and STCW can either require mariners possess, or recommend they obtain, the additional qualification and competency afforded by Ice Navigator Certification.

With respect to enforcement, flag states should pay closer scrutiny to the training that is “approved” as meeting Polar Code requirements. Training material, course training time, actual adherence to the model course requirements and instructor subject matter knowledge must be more closely scrutinized before any course is approved. Flag states can ensure that approved training institutions clearly indicate that trainees must obtain the appropriate CoP.

Owners should conduct better due diligence in accepting training and certification that truly meets the needs of safe operation in polar waters. Port State Control must provide their inspectors with adequate training and clear guidelines to spot the discrepancies to provide preventive assessment as well as control. During the summer 2022 Arctic season, the Paris MoU (an organization of 25 European states and Canada with a mission to eliminate the operation of sub-standard ships through a harmonized system of Port State control) instituted a focused inspection campaign “to verify compliance with the requirements of the Polar Code” for two, two-week periods. This must be broadened to be an annual focus prior to and at the commencement of both the Arctic and Antarctic navigational seasons.

The Polar Code has indeed formed the foundation of a global mandatory standard for polar shipping. The Code and the enabling amendments to SOLAS, STCW (International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers), and MARPOL (International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships) should be constantly reviewed and amended to close gaps and ensure relevance and effectiveness. Where IMO related instruments or guidance is well known to be ponderous and slow, the maritime industry should look to itself and its supporting organizations, such as the Nautical Institute, to close the gaps in the interim.

Captain David Snider is an ice pilot and navigator. He is the Past President of the Nautical Institute and President of Martech Polar Consulting Ltd.