By Vincent Geloso, July 7, 2023

The grocery sector has been under constant scrutiny by politicians and regulators for the rising prices of food bought in stores. The latest to enter the fray is the Canadian Competition Bureau with its much awaited report on the state of competition in the industry.

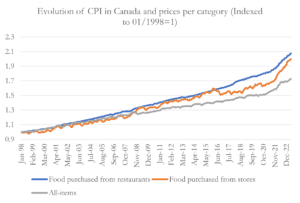

The report uses Statistics Canada data from the last two years which show that price increases for food bought in-store are outpacing the general rate of inflation. This is then tied to the wave of mergers in the industry that has taken place since the late 1990s. The assumption made by the Bureau is that the number of firms in the industry – which is lower now than in 1998 – is the best indicator of competition. Thus, more review of mergers is argued to be warranted.

There are, however, multiple problems with both the evidence the Board uses and the assumptions it makes to reach that conclusion.

The first set of problems is tied to the data used. If one decides, unlike the Competition Bureau, to extend the study of prices for food bought in stores back to 1998, one will find that grocery prices have increased faster than inflation. However, looking at prices for food bought in restaurant yields the same conclusion – they, too, have increased faster than inflation. This is one clue that the report’s conclusion is weak, because the restaurant industry is known to be highly competitive. Why would prices increase as fast in that competitive industry as the supposedly uncompetitive grocery industry?

The answer lies in what is actually being measured by Statistics Canada when it collects price data. Many will assume that the price being recorded for, say, a pound of beef is the price of the good itself. However, that is not the case. The grocery industry has increasingly been incorporating into its pricing a greater number of services in the goods that we buy at the store. This can be seen with already cleaned produce for salads, pre-seasoned and pre-marinated meats, pre-cooked meats, sliced vegetables, etc. These items, which are growing in popularity (not just in Canada, but in the USA and Europe as well), were not an important feature of what grocery stores offered less than a decade ago.

This means that if you looked at what Statistics Canada listed as the price of a pound of beef in 1998, you were probably looking mostly at the price of the beef itself. Today, that figure represents not just the beef but all the bundled labour services that come with it. This has value to consumers, as it saves them time in meal preparation and cooking at home. One way to circumvent this is to look at prices collected by web-scraping — generally, goods sold online and delivered over mail. Because of the shipping component of the services, most of these goods are less likely to be a blend of “goods and labour services”. These indexes (largely produced for the USA only) show that grocery prices since 2015 had lower inflation than the overall food prices tracked by government agencies.

As such, the data used by the Competition Bureau is not measuring the same “good and service” over time, which leads it to a false diagnostic. However, this does explain why restaurant prices are also increasing faster than inflation: the demand for prepared meals (either in grocery stores or restaurants) is growing fast.

This brings us to the Competition Bureau’s shaky assumption that competition is measured by the number of firms present in the industry. It is entirely possible for a market to have few firms, or even a single one, because they are the ones that will have the lowest costs of production. In cases like these, mergers might even help consumers if it means an efficient firm can scale up and produce even lower prices.

When a market ends up with a few highly efficient firms, then the only question of relevance is whether these incumbents can be challenged. Just the threat of competition can be sufficient to guarantee a competitive behaviour by a firm alone on a market, and this appears to be the case for the Canadian grocery sector as the Competition Bureau itself admits implicitly. The report points out that some foreign firms are reluctant to enter the Canadian market because profit margins are too small – which is essentially saying that the current firms in the grocery sector are aware that they can be threatened and that they need to provide high quality goods and services at low prices to deter the entry of potential competitors.

We should take the Competition Bureau with a grain of salt as it makes questionable diagnostics and contradicts itself by illustrating that that the industry is actually competitive. That being said, there are policies that could be deployed that could create more potential for entry by competitors. However, this would involve removing the multiple licensing requirements for groceries and stores that provinces impose which limit competition, or that regulatory compliance costs – which are more burdensome to smaller firms trying to grow – should be slashed.

Vincent Geloso is an assistant professor of economics at George Mason University.