This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Brian Lee Crowley, April 13, 2022

Many Conservatives moan about the challenges of being a conservative party in a left-wing country, as if the deck was stacked against them by the electorate’s immutable “progressive” beliefs. What if, however, Canada is a country with deeply held but non-ideological beliefs that are in many ways quite conservative but the Conservative Party constantly misjudges how to connect with those values? If this is correct, then Canada is not the problem. The Conservative Party is.

For an object lesson in how to let underlying conservative values shine through an overlay of long-time progressive government, look to Saskatchewan. Long a bastion of CCF and then NDP government, a place progressives elsewhere in Canada longingly admired from afar, Saskatchewan has decisively shed its NDP allegiance. It has transferred its affections instead to the Saskatchewan Party, a relatively populist amalgam of small-c conservative Tories and Liberals.

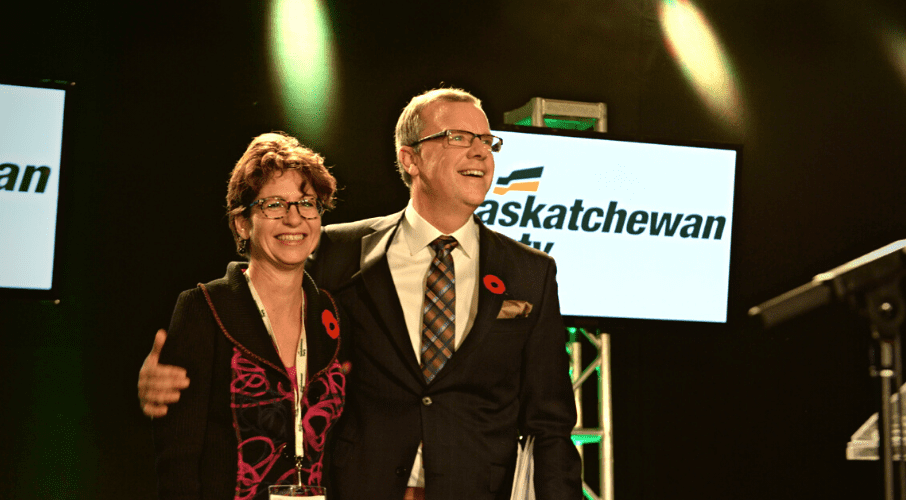

The CCF/NDP ruled Saskatchewan for roughly 46 of the 63 years between 1944 and 2007, punctuated by short interludes of government by the Liberals or the Tories when the electorate judged the NDP needed a time out. But voters always returned to their NDP home, including in the early days of the Saskatchewan Party. The new party was still young, brash and aggressively populist. Successive electoral defeats ground down the party’s sharp edges until, under leader Brad Wall, the party learned how to win the trust of voters while holding firm to conservative principles.

It wasn’t that Saskatchewan people weren’t in their heart of hearts conservative. It was that they worried that an ideologically-driven Saskatchewan Party would throw out the baby with the bathwater.

A major sticking point for Saskatchewan voters was the panoply of Crown corporations that had grown up under the NDP, running everything from telephones to auto insurance. The voters recoiled before the early Saskatchewan Party’s determination to rid the province of these affronts to private enterprise.

Saskatchewan folks are more pragmatic. They were fine with conservative incremental adjustment but resistant to radical populist wholesale change. They preferred the known and comfortable to the unknown and theoretical.Brad Wall’s genius was that he brought a whole different philosophy to presenting conservative-oriented change to Saskatchewan. He didn’t start out with hard-line ideology that promised a sharp break with the past, trying to convince people to accept a leap in the dark.

As Dale Eisler, author of an important new book, From Left to Right: Saskatchewan’s Political and Economic Transformation, argues, the conservative populism expressed by Wall spoke to feelings and values that resonated with the people of Saskatchewan, more Humboldt and Swift Current than Adam Smith and Milton Friedman.

He would often deliver his message in terms of “Saskatchewan values,” things like self-reliance, hard work, resilience, entrepreneurship, dedication and a sense of community. He understood that you appeal to people, not with partisan political rhetoric, but beliefs and attributes the majority of people share. He would always root his policy decisions in those values. In other words, he rose above identity politics to something that most people could agree was true about themselves. The fact that Wall was a skilled and eloquent communicator didn’t hurt either.

The relatively non-ideological nature of the Saskatchewan Party’s appeal dovetails with the non-ideological nature of the mainstream of Saskatchewan and, I would argue, Canadian voters. Most Canadians believe in hard work, family, friends, the community they live in, a private-sector-led economy open to international trade and a government that reflects their beliefs and desires, not one that imposes its beliefs on them.

But they are also practical in their outlook. What appeals to them is politicians who are not rigidly ideological, but able and willing to be pragmatic when necessary. Such pragmatism helps to earn the public’s trust; that makes bigger change possible later as people gain confidence that change is driven by the practical successes of the reforms that went before. Less “Axe the Tax” and “Defund the CBC” and more “Incremental change that respects our history and beliefs.”

As Dale Eisler said to me, the Saskatchewan Party’s populism, “is rooted in conservatism, but has emotional appeal to people who are not overly ideological. What’s needed is a political leadership that rises above identity politics and talks to people in terms of shared beliefs that serve to unify, not divide, while pursuing conservative principles.”

No formula confers permanent political success. But nearly 15 years into the Saskatchewan Party’s reign the party gets six out of ten votes in the province and the NDP just lost another leader after a by-election loss in a normally safe seat. Saskatchewan shows that a progressive past is no bar to a conservative future, but also that understanding and caring about voters’ values beats ideological purity any day.

Brian Lee Crowley is the founder and managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. His most recent book is, Gardeners vs. Designers: Understanding the Great Fault Line in Canadian Politics.