This article originally appeared in the Hill Times.

By Dave Snow, December 1, 2023

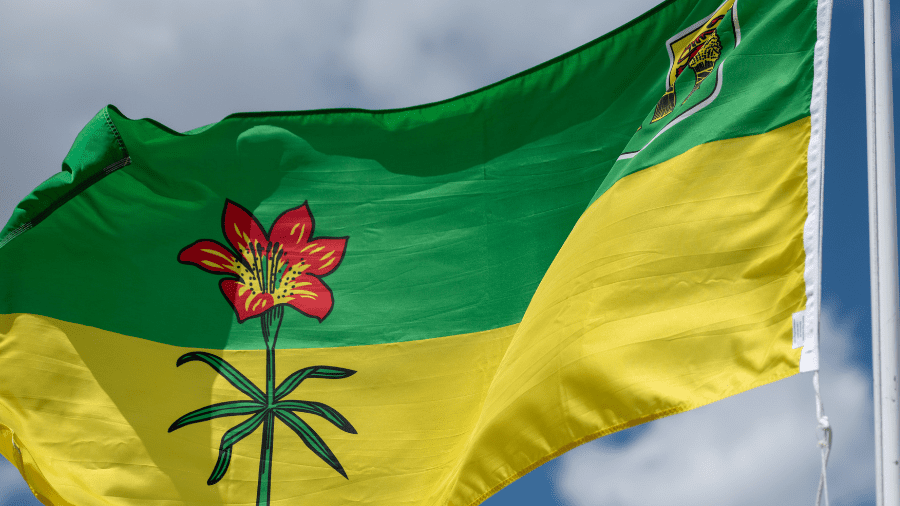

The Saskatchewan government recently introduced legislation invoking the “notwithstanding clause” in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to require parental consent when schools authorize name and gender pronoun changes for students under the age of 16.

The invocation of the clause—which permits laws to operate notwithstanding certain sections of the Charter—has led many to denounce the bill for violating numerous rights, particularly LGBTQ rights, children’s rights, and the right to privacy. Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe has also framed the policy as a rights issue calling the proposed policy the “Parental Bill of Rights.”

Yet the rights in question are far from settled. Parental rights do have a limited legal basis in Supreme Court jurisprudence, but like all rights in the Charter, they are subject to reasonable limits. Likewise, the Supreme Court recognized LGBTQ+ rights in a series of decisions in the 1990s, and has affirmed the rights of “mature minors” to make decisions without parental consent.

However, the Charter contains no textual basis, and the Supreme Court has no direct jurisprudence that would apply to either set of rights claims on the issue of parental consent and children’s pronouns.

The core dispute—whether parents should be informed, and, if so, provide consent when students change their names or gender pronouns at school—implicates foundational questions of parenthood, identity, privacy and consent. It is thus exactly the type of issue for which the notwithstanding clause was envisioned—reasonable disagreement with a judicial decision or existing jurisprudence, in an area of provincial jurisdiction, over a “clash of rights” not directly enumerated in the Charter.

By invoking the notwithstanding clause, the Saskatchewan Party government is signalling disagreement with an anticipated judicial interpretation, and offering its own interpretation that values parental consent more highly.

Whatever policy a government implements in this area, it will involve a limitation on someone’s rights. Children’s rights to privacy are important, as are the rights of parents to be informed of their children’s choices. These are good-faith reasons to support or oppose the Saskatchewan government’s policy.

To be sure, Moe’s decision to invoke the notwithstanding clause indicates that he thinks it is unlikely that his policy would survive a Charter challenge. However, a high likelihood of judicial invalidation does not mean that a policy is necessarily beyond the pale.

The judicial interpretation of the Charter as a “living tree” has become the dominant justification for the extension of rights to areas beyond those contemplated by those who framed the Charter. For good or ill, this has meant our democratically elected representatives are often constrained in making policy on issues over which there is a wide range of reasonable disagreement—including among Supreme Court justices themselves—such as abortion, hate speech, prisoner voting, and the right to strike.

By “constitutionalizing” these issues and putting them beyond the scope of legislative authority, courts have constrained the realm of legislative activity on clashes of rights on which reasonable people disagree.

As I argue in my recent paper for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, the notwithstanding clause was put in the Charter to prevent legislatures from becoming so constrained. The notwithstanding clause was understood by the framers of the Charter as a mechanism to enable legislatures to overrule the judiciary so as to maintain the tradition of parliamentary rights protection. It empowers legislatures to take a side in disagreements about rights, but it also ensures that those disagreements will continue over time. The clause’s five-year expiry ensures that governments that invoke it must face voters before doing so again. Unlike a judicial decision, the notwithstanding clause is likely to promote and extend debate in the legislature rather than prevent it.

As a critical part of the Charter, the notwithstanding clause was designed precisely for policy disputes like parental consent and pronouns in schools—those with multiple competing interests, no easy answers and rights claims from all sides.

Far from being an exercise of raw and unjustified power, the clause is an important constraint on unchecked judicial authority, one which will ensure our elected representatives retain the ability to engage in important policy debates.

Dave Snow is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and an associate professor in the department of political science at the University of Guelph.