By Andrew Evans, March 13, 2024

A slow-moving crisis

Canada faces numerous challenges in every policy space – and it’s only getting worse. Fixing these problems will require fresh thinking about how government creates policy.

To drive more effective policymaking, we need a new approach. Effective policymaking must think not only about today but also anticipate policy solutions for the time ahead. It also needs to include political oversight, to ensure accountability in government.

Despite the public service being the biggest it has ever been and seeing a 40 percent increase since 2015, Canadian state capacity has taken a serious hit in recent years.

This is not a new concern. Thought leaders from across the political spectrum have identified this problem, pointing to a record of failures and atrophy. The former head of the civil service now calls for public sector reform, and Canadian scholarly experts call for restructuring. The key issue they identify is a civil service that has become enfeebled by its own size and is being asked to do too much.

Pulled in too many directions, the public service has strayed from its core mission – policy implementation, not policy ideation. Basic things that should be within its reach, like developing an app, instead have been increasingly farmed out to consultants, resulting in skyrocketing costs and questionable accountability.

Since the 1990s, Cabinet’s influence has declined, while the power of the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) has increased. This power shift has resulted in significant changes to policymaking, with decisions increasingly made by a more centralized PMO. While some might yearn for a return to the more decentralized governments of yesteryear, the political reality is that this concentration is firmly solidified, and to solve the issues we face, we must engage with the system as it is.

While the concentration of power has been to the advantage of the prime minister in power, a drawback has been the fact that the senior members of the bureaucracy, or a small cadre of PMO or Minister’s Office staff, has been asked to solve nearly every federal issue. There is simply a shortage of time, expertise, and bandwidth.

This reliance on a small group has led to incomplete solutions to complex policy problems. In turn, this compounds the seriousness of the situation we have today, with policy problems snowballing and cascading. But this is a reflection of modern expectations that are placed on an outdated policymaking structure. In an increasingly interlinked and faster-moving world, it is simply unrealistic to expect that a small group of policymakers in Ottawa can solve all the challenges we face.

For continued peace, order, and good government, we need Canada’s PMO and civil service to evolve. We need to lean into political power trends, equip the PMO with the tools it needs to govern effectively, and realign the public service to its core mission so it can thrive.

Thinking in systems

In 1960, newly elected American President John F. Kennedy sought to address very similar issues in the United States. He saw the federal bureaucracy as too cautious and slow, with an inability to effectively work across departments.

At the time, the administrative body of the White House was still nascent, and Kennedy viewed its development as central to fixing the problems facing the country. Using the lessons of the National Security Council (founded in in 1947), he established the forerunners for what are today the National Economic Council and the Domestic Policy Council.

Each of Kennedy’s successors iterated on the design of the councils, developing them into the bodies they are today, adding as they felt necessary. All three councils are bodies where Cabinet members and others meet to coordinate policy and are complemented by staff who work to provide policy ideas and ensure effective implementation. This complement of staff allowed for the hiring of politically aligned staff roles – a half-step away from the issues of the day, while still a part of the White House – to oversee the ideation, execution, and implementation of the president’s agenda.

In Canada, much of this does not occur in the PMO, where the issues of the day dominate priorities, or they are farmed out to the Minister’s Offices. There, policymaking is exposed to a series of other motivating factors, and while it may incorporate more input from sector-specific stakeholders, it can also be diluted from the original intent as conceived by the PMO.

There are also a multitude of Cabinet committees in Ottawa. With ministerial membership, they help to illustrate and oversee the priorities of the government in power but are typically used to vet policy that is in the final stages before public release.

This helps to involve ministers, keeping them content and part of the team. But overall, they carry little weight in government decision-making except at the margins, such as on how to communicate a policy or address a specific stakeholder that should be aware of the proposed changes. These committees have no independent permanent staff dedicated to thinking about policies or maintaining oversight of instructions given to ministers. This is downloaded instead to the individual ministry, or in some cases, the Privy Council Office, decreasing accountability.

Aligning incentives

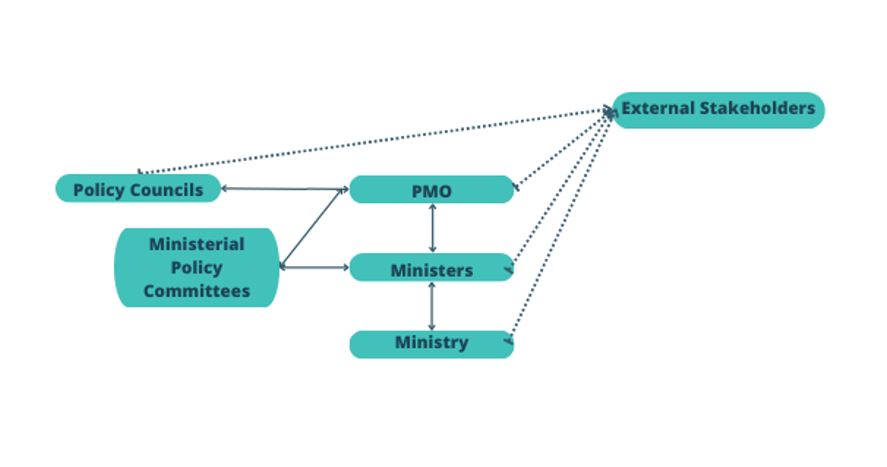

Taking inspiration from the White House, the Prime Minister’s Office should recognize the central role it plays and expand to match its mission, creating policy councils staffed by the PMO. This would give it greater control over the policymaking process and address the wider issue of state capacity deficiencies in the civil service.

These Policy Councils not only would consist of PMO staff, but also possibly non-governmental individuals selected by the PMO, as well as representation from agencies, ministries, and minister’s offices as required.

With more ad-hoc and longer-term policy deliberation, the Policy Councils could offer key policy advice while escaping from previous timidity in policymaking. This would break the monopoly that the public service currently holds in policymaking, while not sidelining the advice of the public service – allowing for a greater diversity of opinions.

Effectively, these groups would function as government policy think tanks, providing innovative solutions and advice to the prime minister on issues that may not even be a problem today. This extra layer of policy vetting would reassure the prime minister that the advice being provided is not simply knee-jerk political reaction nor bureaucratic retread, helping to engender more confident political decision-making.

Relieving the civil service of its role as being policy originators will address the core issues that have caused it to fumble basic implementation issues. Original policy creation is not the ideal role of the bureaucracy, since there are few organizational incentives for the bureaucracy to provide creative, original policy.

As a large, multilayered structure tasked with ensuring that the services of government function and policy is implemented, a bureaucracy can do lots of repetitive, albeit complex, tasks very well. A high-functioning bureaucracy can even do iterative implementation well, improving on the performance of those tasks. But bureaucracy simply isn’t the place to look for innovative solutions. Recognizing these comparative advantages opens the door for better government.

Existing Cabinet policy committees would continue to function, but this approach would put less pressure on the vetting of the substance of policies themselves and more on the communication/political considerations. Again, this is another alignment of where Cabinet ministers can provide value to the government’s policymaking process.

For individual Cabinet ministers and ministerial staff, their role would be to ensure the smooth implementation of the PMO’s agenda, which would be created by the PMO and the Policy Councils. This would concretely align ministerial incentives and mirror them with the bureaucracy, providing important political oversight to the implementation of PMO’s policy.

Governance evolution

The history of Canadian governance has been an ever-evolving story, and it will continue to change. Good government is, and should be, something for which everyone strives. The current Liberal government even showed signs of being open to these changes by proposing a “Council of Economic Advisors” in 2021 before becoming waylaid with other priorities.

By building on existing political trends, while giving the PMO the tools it needs to govern effectively, we can reaffirm the commitment of responsible government. Restoring the public service to its core mission will allow it to focus on delivering good government for Canadians.

Our collective national journey has always involved changes to our ways of governing – evolving to meet new times and challenges. With the increasing frequency of bad government, it is now clear more than ever that the problems of today can’t be solved by the tools and solutions we have at hand. Yesterday’s approaches will not solve tomorrow’s problems, but we can fix those deficiencies today.

Organizational Diagram (Proposed)

Andrew Evans is an experienced Canadian policy professional. He is currently studying for a Master of Public Administration in Energy Policy from Columbia University.