By Balkan Devlen and Jonathan Berkshire Miller, January 2, 2024

In the wake of a 2015 election victory, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau famously announced: “Canada is back”. Unfortunately, the hopes of 2015 seem dated in 2024 as Canada struggles to find its place amid the intensity of rising geopolitical competition.

Federal polling now strongly suggests that Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives are likely to win the next election. This raises an important question: how might a new Conservative government offer a serious rethink of Canada’s approach to international engagement in order to make “Canada is back” something other than a dated slogan?

As tempting as it would be for a cost-conscious Poilievre government to see Canada’s foreign aid budget purely as a source of savings, international development is, alongside diplomacy and defence, a key pillar of Canadian statecraft. The failure to strategically coordinate Canada’s efforts on these three fronts means that Canada’s engagement on the global stage has had very little impact in recent years.

Canada has put international engagement on autopilot. We have been content with drifting along, doing things because that’s the way we have done them for the last 30 years. This drift is no longer appropriate or sustainable. Perhaps, in the glow of the end of the Cold War and a couple decades of relative peace and security, Canada could get away with unfocused or even blatantly mistaken priorities for international cooperation, but in today’s more tumultuous reality we don’t have that luxury.

Strategic engagement must start with a full review of Canada’s international cooperation activities. This review should address the unfortunate reality that Canada has developed a reputation as a nation that wants to be at every multilateral table but without becoming a serious contributor at any table. The question we need to ask is: which tables do we need to sit at and which ones do we need to get up and leave? Canada has limited resources. Spreading them out thinly to be in as many places as possible has failed. We need to be deliberate about where we are rather than seek to be everywhere.

In deciding which multilateral organizations we should be invested and involved in we must assess whether they are in alignment with our national interest and stated policy goals. In an age of geopolitical competition, it cannot be taken for granted that every multilateral organization meets that test. We should not be afraid to walk away from organizations that do not serve a strategic purpose for Canadian interests, such as the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) which is essentially a tool for CCP influence in the world.

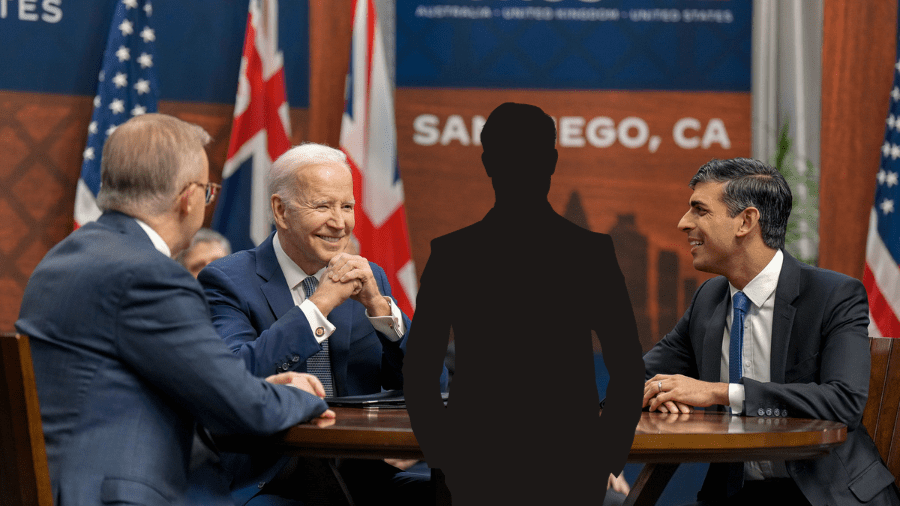

Rather than a blind commitment to multilateralism, there should be a turn to “minilateralism” – that is issue-based, narrow groupings of like-minded states. This is the future of international cooperation and Canada thus far has failed to be invited into some of the most significant minilateral organizations (such as AUKUS or the QUAD). As geopolitical rivalry intensifies it is crucial that Canada works more closely with those who share our common values and objectives. This allows for some of the benefits of multilateralism without the risk that organizations become paralyzed over basic agreement on their purpose.

We need to also start thinking of international cooperation as a part of statecraft more broadly, and not simply as some sort of charity. Good intentions are not a substitute for clear goals and metrics to measure success. Such metrics need to be clearly linked with advancing Canada’s interests including strengthening rule of law and free markets abroad, pushing back against state capture by authoritarian actors, fighting corruption and financial crimes, contributing to security, stability, and societal resilience in developing countries, improving outcomes related to global health and climate change, and opening new markets for Canadian businesses. We should have a real interest in a robust international cooperation program that advances projects that make a difference but that requires measurable evidence of the good accomplished by any given investment.

Demonstrating the results is also important for another element of a renewed approach. This strategy will only be successful if it engages the Canadian public on why a focused international cooperation strategy is in Canada’s interest. It is especially key to reach out to some nationalist conservatives who may be skeptical of the value of foreign aid and international cooperation, individuals for whom the arguments that Canada should totally disengage are appealing. To reach these potential skeptics a government will need to be able to articulate the clear linkage between Canadian interests and foreign aid, international cooperation, and global engagement.

Finally, a renewed approach should be one that looks beyond government to bring in the private sector, NGOs, faith groups, and diaspora organizations in formulating and carrying out an international cooperation strategy and moving beyond state-to-state foreign aid. Canada’s International cooperation should not narrowly reflect the values of a handful of officials in Ottawa but should reflect a much broader, more inclusive set of generally agreed upon principles and should serve the interests of the nation as a whole.

Canada cannot afford to disengage in a dangerous world, but equally, we cannot afford engagement that fails to produce results or fails to protect our national interests. It is time to get serious about getting Canada back on the world stage.

Balkan Devlen is Senior Fellow and the Director of the Transatlantic Program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Jonathan Berkshire Miller is Senior Fellow and the Director of Foreign Affairs, National Defence, and National Security at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.