This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, January 22, 2025

When Donald Trump promised 25 percent tariffs on all Canadian exports a few months ago, many hoped it was bluster. Turns out, it might have been—but then again, maybe not.

Following his swearing-in and second inaugural address, the president directed the goverment to investigate trade policies and relationships, and “remedy persistent trade deficits.”

He initially stopped short of across-the-board tariffs, omitting mention of Canada in his address, though later in the day declared February 1 as the day tariffs will be imposed on Canada.

Canadian government, policy, and business leaders have been seized in recent weeks with how to respond if tariffs did come. Parsing the Trump administration’s true plans on these issues is clearly a difficult endeavour. Regardless, Canada must be prepared for the worst eventualities.

Among the many ideas floated, one in particular has sparked fierce debate: restricting or taxing oil and gas exports to the U.S.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has come under fire for rejecting this option, but she’s right to push back. Cutting off such a vital industry would be devastating for Canada’s economy and play directly into the U.S. administration’s hands by giving them a convenient scapegoat for rising energy prices.

“Rather than blaming Trump for rising prices, American consumers might blame Canada and become more supportive of Trump’s tariffs,” wrote my wise University of Calgary colleague Lisa Young.

It’s common for political leaders to say that “all options are on the table,” but bad ideas really shouldn’t be.

If retaliation must be done, it should be smart, targeting areas where the impact on Canadians is minimal but still sends a clear message—like consumer goods that are easy to replace, which Canada seems poised to focus on in its initial $37 billion response. That still costs Canadians—with potentially little effect on the U.S.—but the consequences are manageable. At least for now. As retaliation escalates, costs grow rapidly.

Even better than retaliatory tariffs and export restrictions would be a renewed focus on strengthening Canada’s economy so we’re less vulnerable to external shocks in the first place.

As an added bonus, getting our own economic house in order by improving the investment environment, easing regulatory barriers, modernizing our tax code, and so on, could potentially shrink or eliminate President Trump’s primary concern: the U.S. trade deficit with Canada.

The economic importance of oil and gas exports

But first, why would restricting oil and gas exports be costly and unwise?

When Canadians outside Alberta think of major industries, they often picture auto manufacturing before oil and gas. The simple reality is that oil and gas bring in far more income and support far more employment than any other sector.

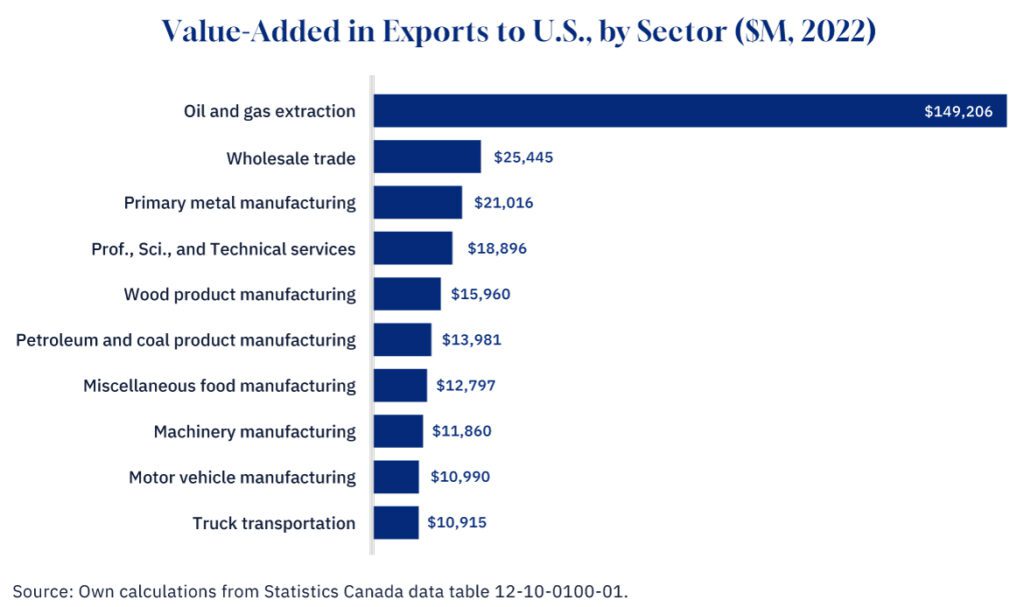

According to the most recent data from Statistics Canada, Canadian workers and business owners earned nearly $150 billion in income from oil and gas exports to the U.S. in 2022, dwarfing other sectors. By contrast, income from motor vehicle manufacturing exports accounted for $11 billion (add in parts, bodies, and trailers and you roughly double this).

While exports of motor vehicles to the U.S. are higher than this ($35 billion), much of the revenue is offset by the heavy use of imported intermediate inputs by the sector, many of which originate in the U.S. itself. This means the actual income earned by Canadians from this sector is far lower than commonly assumed.

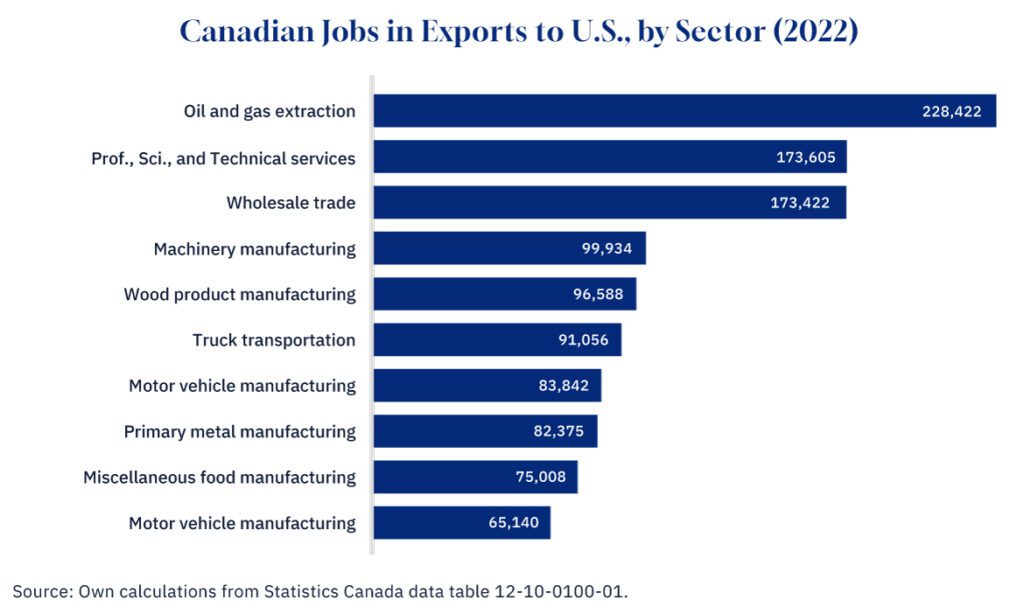

It’s not just about the income generated from exports to the United States that matters; the potential impacts on jobs are also important. And even by this measure, oil and gas leads the pack. The number of Canadian jobs embodied within oil and gas exports to the U.S. accounted for over 228,000 jobs in Canada. And fully 40 percent of those jobs are outside Alberta.

By comparison, the next-largest sectors—professional, scientific, and technical services, and wholesale trade—each supported just over 170,000 jobs tied to U.S. exports. Meanwhile, motor vehicle manufacturing exports to the U.S. accounted for approximately 84,000 jobs, or about one-third of the total from oil and gas extraction.

Blocking oil and gas exports therefore makes even less economic sense than retaliating against the United States by restricting auto exports—which would itself be a foolish decision, and luckily not one anyone has seriously suggested.

It gets worse. Over time, the costs of restricting energy exports would grow even larger. Such a move would likely prompt the U.S. to reconfigure its infrastructure, refineries, and policies to reduce reliance on Canadian oil permanently. The fleeting costs we might impose on the U.S. today would risk permanently shrinking Canada’s economic potential.

A better way

Rather than engaging in tit-for-tat retaliatory measures, Canada might achieve more by addressing some of the primary concerns that have been raised by the U.S. administration. Recent concerns have focused on border security, migration, and fentanyl trafficking. Whatever the merits of these issues, Canada has rightly already moved to beef up border security. Additionally, Canada should follow through on its long-standing commitment to increase military spending to 2 percent of GDP, a pledge we have consistently failed to meet.

But one of President Trump’s longest-standing complaints is the U.S.-Canada trade balance, which he claims amounts to a “$200 billion subsidy to Canada.”

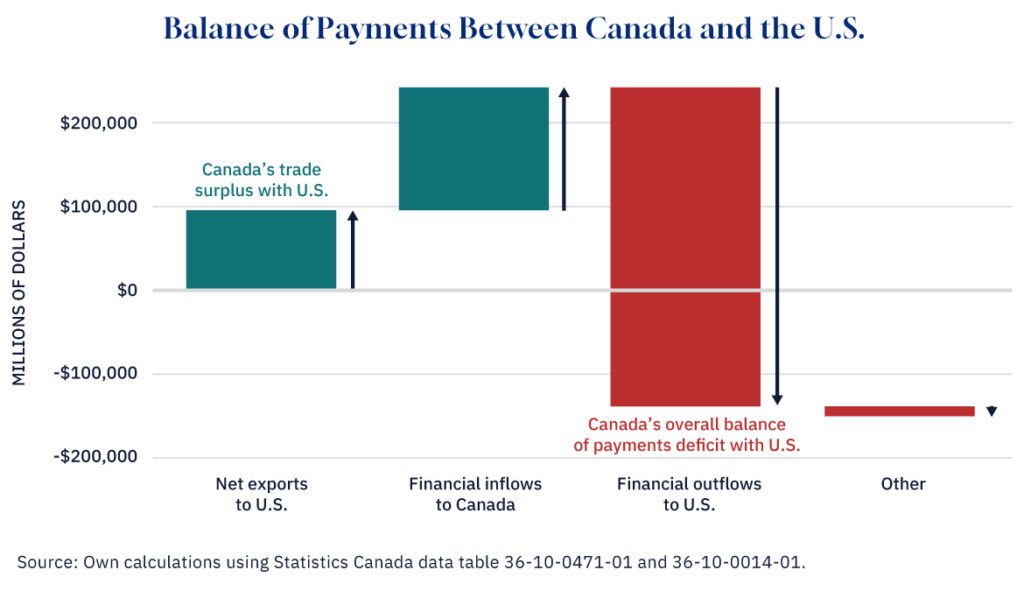

This fixation on bilateral trade deficits is misguided. Canada’s trade surplus with the U.S. is almost entirely driven by oil and gas exports, and bilateral trade balances are poor indicators of economic health or fairness. Trade relationships are about mutual benefits, not zero-sum math.

But trying to convince the president of this is likely pointless. So instead, Canada could take steps to shrink the trade imbalance—or even turn their trade deficit with us into a surplus—while strengthening our own economy in the process.

For a country with a flexible exchange rate like Canada, trade balances are always offset by financial and capital flows, which means any trade surplus is matched, dollar for dollar, by capital outflows. (That’s not true with respect to each trading partner, to be clear, but it is true overall.)

In Canada’s case, the significant trade surplus with the U.S. is more than offset by roughly $400 billion in annual financial outflows to the U.S. In 2023, resulting in a net balance of payments deficit for Canada in its overall relationship with the U.S.

Such financial outflows may be a symptom of a weak Canadian economy and an unattractive investment environment. Much has been said about Canada’s recent economic malaise, and it’s hard to overstate just how significant an economic hole we’ve dug ourselves.

If we improve our investment climate—by reforming business taxation, easing regulatory burdens, addressing persistent issues like interprovincial trade barriers, removing political interference from major project decisions, expanding key infrastructure, and so on—Canada could attract far more investment.

Beyond a good in and of itself, boosted investment inflows would lead to a stronger dollar. Imports would therefore become less expensive and exports more costly for international buyers, thus helping reduce our trade surplus. Importantly, this would also come with higher productivity, faster economic growth, improved living standards, higher wages, and lower prices for many goods.

So instead of retaliating with measures that harm ourselves far more than the intended target, Canada should (at long last) focus on strengthening its own economy. This would address both the root causes of our current weakness and the central irritant in Canada-U.S. relations, as far as President Trump sees it anyway.

That’s the better idea—and one we should embrace.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary and a research fellow at The School of Public Policy.