By Philip Cross

By Philip Cross

May 31, 2022

Overview

Inflation continued to accelerate and spread in 2022, contrary to central bank assurances that higher prices were a short-term “transitory” phenomenon that would dissipate quickly as global supply chains returned to normal. It is increasingly evident that inflation originated in excessive monetary and fiscal stimulus during the pandemic, which aggravated government actions that distort the housing, energy and labour markets. Labour shortages and job vacancies are much greater in Canada and the United States than in Europe or Asia, reflecting both much larger fiscal deficits in North America and government support programs breaking rather than preserving the link between employers and employees.

Meanwhile, central banks discounted the inflationary potential of rapid money supply growth during the pandemic, the culmination of their downplaying of the importance of monetary aggregates since abandoning monetarism in the 1980s. Without an increase in the money supply, shocks to the supply-side of the economy (such as higher oil prices) would not be transmitted and embedded throughout the economy but remain a localized and temporary problem – one that central banks believed they were confronting when prices began accelerating in 2021. Now central banks, including the Bank of Canada, are scrambling to contain inflation with large hikes to interest rates that run the risk of both recession and disruptions to financial markets as participants adjust to much higher interest rates than was thought possible only a few months ago.

Introduction

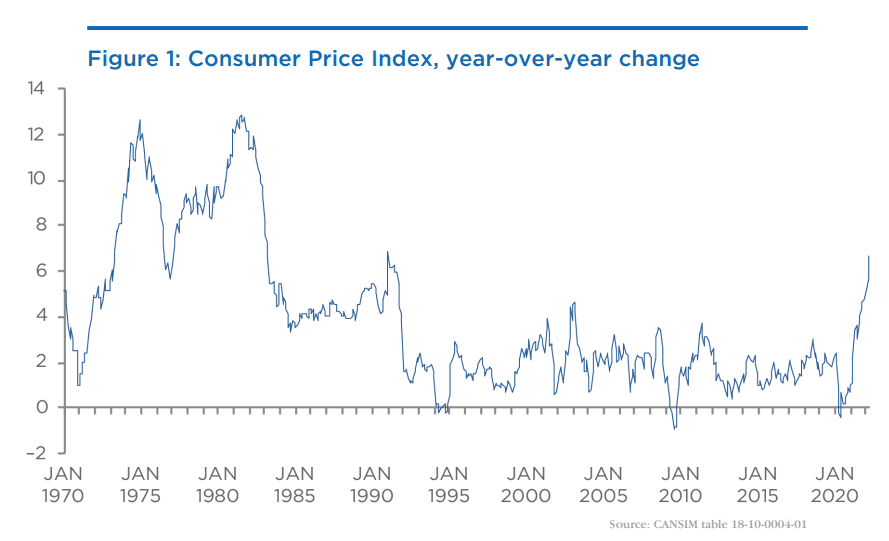

Canadians are currently experiencing the sharpest and most prolonged resurgence of inflation since the early 1980s. Inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) reached 6.8 percent in April 2022, its highest rate since 1983 except for a one-month spike to 6.9 percent in January 1991 when the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced (Figure 1). Actual price increases in Canada probably are even higher, as Statistics Canada does not yet survey used cars where prices have shot up during the pandemic.

Inflation is not confined to a few high-profile components such as food and energy. Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine did aggravate the increase in food and energy prices, as together they supply about 10 percent of the world’s oil and 30 percent of wheat. However, over two-thirds of the components of Canada’s CPI have increased over 3 percent, well above the target of 2 percent. The Bank of Canada sees inflation persisting at 4 percent by the end of 2022.[1]

Why inflation matters

The recent surge of inflation is important for several reasons. Higher prices erode purchasing power, especially for people living on fixed incomes. The Bank of Canada estimates that inflation of 5 percent costs the average person in Canada $2000 a year (Macklem 2022, 2). The estimated $200 billion of extra savings built up by households during the pandemic will be exhausted in less than a year at the current rate of decline of real incomes. Even people receiving government benefits indexed to inflation will see their purchasing power eroded, since they have to wait a year before their incomes are adjusted up; pensioners, for example, will have to deal with much higher prices throughout 2022 before their income is adjusted up early in 2023 for inflation.

More broadly, inflation depresses productivity by interfering with the efficient allocation of resources because price signals in the economy become difficult to interpret. An inflationary environment discourages business investment because firms have trouble forecasting what costs and returns will be in the future. Already, business confidence in Canada fell for the third quarter in a row, as 46 percent of firms said rising labour costs are affecting investment plans (Heaven 2022).

Fighting inflation also entails costs to the economy. As a result of higher and more sustained inflation, the Bank of Canada has raised its interest rate by 75 basis points and warned further increases are inevitable. So far this year, the yield on the federal government’s 10-year bonds doubled to 3.0 percent after falling below 1.0 percent during the pandemic. The US bond market suffered its largest quarterly loss to start 2022 since the early 1980s, and total returns on bonds fell 9.5 percent for the year through the end of April (Goldfarb and Gillers 2022). Bond losses grew to 12 percent in early May when interest rates surpassed 3.0 percent.

Obviously, raising interest rates slows growth, with the risk that the economy will fall into recession and a small percentage of workers will lose their jobs. However, central banks have to weigh this against the higher prices everyone pays if inflation is not reined in. Nor are recessions inevitable, as central banks always strive for a “soft landing” where the economy slows enough to dampen inflation without tipping into recession. However, as former US Federal Reserve Board Governor Donald Kohn noted, central banks are much more likely to engineer soft landings if they act before inflation rises substantially (Miller 2022). This is clearly not the case today as central banks were slow to respond to higher inflation.

Compounding the chance of a recession is the mostly overlooked risk that higher interest rates trigger losses in the financial system. Past cycles of tighter monetary policy often led to sharp corrections in financial markets. While the public is most familiar with corrections in the stock market (such as the 1987 crash), more esoteric markets also have been severely affected when central banks tighten financial conditions. These include the Mexican peso crisis in 1994, the collapse of the Long-Term Capital Management hedge fund in 1998,[2] and turmoil in the repo market in 2018.

The risk of severe dislocations in financial markets is particularly elevated in the recent environment of interest rates near their zero lower bound, which led many investors to make decisions based on the expectation that rates would stay low indefinitely. The sudden and unexpected increase in interest rates in 2022 could lead to unexpected outcomes and sudden sell-offs in markets, putting further downward pressure on the economy.[3] As Warren Buffet famously said, “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.” Unexpected moves in financial prices often expose investors who have taken excessive risks.

Inflation varies in different countries

Inflationary pressures are different around the world. They generally remain quite low in Asian countries such as China, Japan, Taiwan and Malaysia. Superficially the rate of inflation seems similar in Europe and North America, but its origins are quite different. In the EU, the CPI is rising near 8 percent, comparable to the increase in the US (Canada’s rate would be closer to 8 percent if used car prices were measured).

The EU is better able to claim that supply shocks have been a larger source of their inflation than Canada or the US. Food and energy are playing a much larger role in raising prices in the EU. This reflects the much greater impact of energy shortages in the EU, which began late in 2021 (partly due to the mismanaged transition to renewable energy) and worsened significantly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February disrupted the flow of oil and gas from Russia. Germany immediately suspended the Nordstream2 gas pipeline from Russia, the EU quickly moved to stop all oil imports from Russia, while Russia cut off gas to countries that refused to pay in roubles. In particular, natural gas costs soared to US$33 per MMBtu in Europe versus US$8 in North America. Meanwhile, food prices in the EU rose 7.1 percent, but the increases averaged 20 percent in Eastern European countries that were affected by the war. Food inflation in Western Europe remained below 6 percent.

Excluding food and energy prices, the CPI rose 3.6 percent in the EU, versus 6.5 percent in the US (Canada’s rate of 4.6 percent would be closer to the US, if adjusted for used car prices). The lower underlying trend of core inflation in the EU is one reason European interest rates remain much lower than in North America, with 10-year bonds still below 1 percent.

Fiscal stimulus fuels inflation in North America

There is a reason inflation is similar in Canada and the United States and different from Europe. Canada and the US pursued the most expansionary fiscal policies among large nations during the pandemic, running fiscal deficits of about 15 percent of GDP. This compares with a deficit of 6.8 percent in the EU. The enormous fiscal stimulus in Canada and the US resulted in unprecedented increases of household incomes and declines in business bankruptcies, the opposite of what usually occurs during a recession. President Biden was typical of government leaders in dismissing the inflationary risks of fiscal stimulus, proclaiming that “When it comes to the economy we’re building, rising wages aren’t a bug, they’re a feature” (quoted in Timiraos, 286).

Economists at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank estimate fiscal stimulus accounted for 3 percentage points of the 5 percent inflation rate in the US late in 2021 (Jorda et al. 2022, 4). In other words, more than half of inflation in 2021 can be attributed to the extraordinary boost to household disposable incomes during the pandemic (the study does not try to separate whether stimulus raised inflation by boosting household demand or depressing labour supply when people left the labour force due to generous government support). Since fiscal stimulus to household income was slightly larger in Canada than in the US, it seems safe to conclude it had at least as large an impact on Canada’s inflation rate.

The large transfers to households from governments in Canada and the United States disrupted the labour market because both sent money directly to support households that lost income during the pandemic rather than through the employer to employees. This broke the link between workers and their employer. This contrasted with “[t]he European-style approach…who favored the idea of preserving employer-employee relationships.” (Timiraos, 235)

The difficulty of re-establishing that connection is one reason job vacancies are much more numerous in North America than in Europe, where governments treated them as furloughed workers. In the US, the number of job vacancies (11.5 million) is nearly double the number of unemployed (6 million), while in Canada the 1,031,000 vacancies are essentially equals the 1,086,000 unemployed. Job vacancies and labour shortages are clearly causing supply disruptions and putting upward pressure on wages, with average hourly earnings rising 5.5 percent in the US and 3.3 percent in Canada in the year to April 2022.

The greater disruption of labour markets in North America than in Europe may actually boost productivity more in the long-term even if it raises costs and prices in the short-term. As The Economist (2020) observed, by allowing workers in North America to leave their employer and still receive benefits, “the re-allocation of labour from dying industries to up-and-coming ones is happening at speed.” The re-allocation of labour is likely to be substantial, as numerous services industries such as travel agencies, office support, and formal restaurants may not recover to pre-pandemic levels for years, if ever.

The large movement of workers between jobs (more so in the US during what is being called the “Great Resignation”) usually results in higher incomes over the long-term. A recent Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI) paper noted that workers who switch jobs experience higher income growth than those who stay put (Cross 2019). The prospect of higher incomes was even greater due to the pandemic since job losses were concentrated in industries with below average wages, such as accommodation and food and retailing. While job churn is disruptive for employers and aggravates shortages and inflation in the short-term, it may boost productivity and incomes in North America in the longer-term. However, that is little solace for central banks faced with higher inflation today.

Central bank forecasts underestimated inflation

Central banks, notably the Bank of Canada and the US Federal Reserve Board, misdiagnosed the initial upturn of inflation in 2021 as transitory and substantially underestimated its virulence. As recently as July 2021, the Bank of Canada predicted inflation would return to its 2 percent target by the end of the first quarter of 2022 (Bank of Canada 2021). Instead, the CPI rose 6.7 percent year-over-year in March 2022. The Federal Reserve Board in December 2021 forecast inflation would cool to 2.7 percent by the end of 2022, and still maintained in March 2022 that inflation would subside to 4.1 percent at year end. In the first quarter of 2022, the Fed’s preferred measure of core inflation (the price index for personal consumption expenditures, excluding food and energy) rose 5.2 percent annually. The delay in correctly diagnosing inflationary pressures explains why central banks are aggressively raising interest rates by half a percentage point instead of the usual quarter point increments.

It is not obvious why central banks were so oblivious to the potential for inflation resulting from the extraordinary stimulus injected into the economy during the pandemic. Perhaps it reflects that central banks were reacting to their over-emphasis on inflation leading up to the 2008 financial crisis. One study of transcripts of Federal Reserve discussions of monetary policy found 468 references to “inflation” in the June Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting versus only 35 for “systemic risks/crises.” Even the day after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, widely considered the beginning of the acute phase of the financial crisis on September 15, 2008, the FOMC meeting contained 129 mentions of “inflation” and only four for “systemic risks/crises” (El-Erian 2016, 43). This over-estimation of inflationary pressures continued for the next decade. Powell admitted persistently too high inflation forecasts by the Fed led them to focus on actual inflation rather than forecasts, which contributed to the Fed acting too late in 2021 (Timiraos 2022, 279). The Bank of Canada has a similar bias of over-estimating CPI inflation.

Without a working model of inflation, poor forecasts are inevitable

The difficulty central banks have forecasting inflation reflects that economists have no working model to accurately predict inflation, as noted in a recent MLI paper (Cross 2021). Most forecasts are based on some variant of the Phillips Curve that relates inflation to unused resources in the economy, sometimes augmented by a measure of inflationary expectations. However, it was evident since at least the 2008 global financial crisis that the Phillips Curve relationship had broken down. Conventional measures of inflation such as the CPI consistently were lower than the Phillips Curve predicted. At the same time, there was considerable inflation in asset prices, which the economics profession and central banks increasingly ignored starting in the 1990s (Timiraos 2022).

While still Governor of the Bank of Canada, Stephen Poloz provided some insights into how the central bank forecast inflation. He said “[t]he place to start is with economic models…but we need to apply real-world judgment before reaching a policy decision. A lot of this judgment comes from conversations with people” (Ibid., 2). He added that persistently low inflation in the late 2010s “led us to pay greater attention to forces pushing inflation down” (Ibid., 4). This bias to focus on the forces dampening inflation was aggravated when prices fell early in the pandemic. The result was the Bank of Canada and the Fed were wary of deflation and discounted the possibility of a resurgence of inflation.[4] Central banks touted their success in stimulating the economy during the pandemic but never discussed what would happen if inflation accelerated quickly. Jeremey Powell, who brings a non-economists perspective to central banking, alone urged his Fed colleagues at his swearing-in ceremony to “give serious consideration to the possibility that we might be getting something wrong.” (Quoted in Timiraos, 74) Such humility is rare in central banks.

The money supply was ignored

Mainstream economics, especially as practiced in central banks, largely ignores the role that the money supply and government deficits play in creating inflation. As a result, the sharp increase in the money supply and the record amounts of government debt issued during the pandemic were not treated as red flags for mounting inflationary pressures.

The reason central banks ignored the inflationary implications of expanding money supply during the pandemic originates in their unhappy experiment with monetarism in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that time, the Federal Reserve Board and the Bank of Canada dispensed with targeting interest rates and instead shifted their goal to controlling the growth of the money supply, letting interest rates rise to whatever level was needed to achieve their monetary goals.

This change in monetary policy allowed interest rates to move rapidly in response to inflation, instead of the small, incremental changes to short-term rates that “tended to be too little, too late to influence expectations,” in the words of Paul Volcker, then Chair of the Fed (quoted in Timiraos 2022, 39). In less than a month after the Fed adopted its new operating procedure on October 6, 1979, the federal funds rate jumped from 12 percent to 16 percent, eventually peaking at nearly 19 percent (Kliesen and Wheelock 2021, 76). This was a clear, unambiguous signal to everyone that the Fed was now single-mindedly committed to lowering inflation.

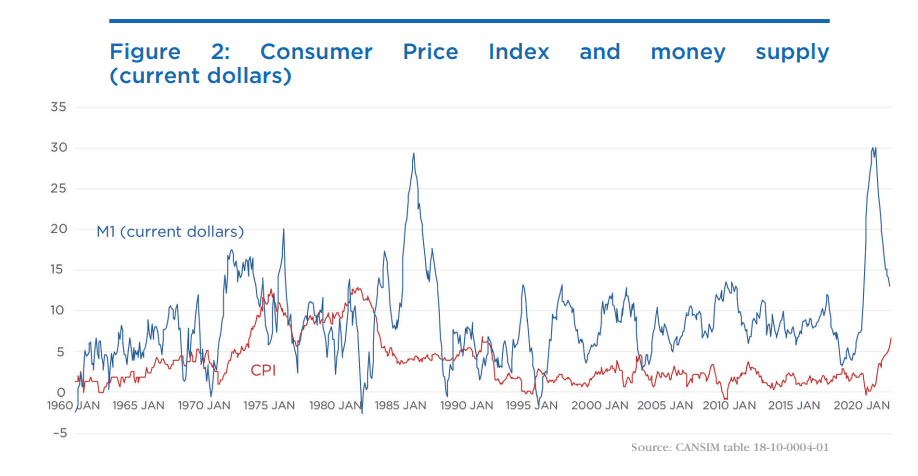

However, controlling the growth of the money supply proved exceedingly difficult in practice. Both money supply growth and its relationship to the economy became unstable in the early 1980s for a variety of reasons (notably innovations in a financial system struggling to cope with high prices and interest rates). The disconnect between the money supply and inflation is evident in Figure 2, when a large increase in the money supply in the 1980s was not followed by higher CPI inflation. The result, in the words of former Bank of Canada Governor Stephen Poloz, was “that the future relationship between money and inflation could not be relied upon sufficiently to warrant continued use of monetary targets. Governor Bouey famously said at the time, ‘We didn’t abandon M1; M1 abandoned us’” (Poloz 2022, 150)

Canada and the US adopted monetarism because the 1970s showed that supply shocks such as soaring energy prices would not have had as large an impact on CPI inflation without an accommodative increase in the money supply. Higher energy prices by themselves substantially reduce household purchasing power and dampen demand and prices elsewhere in the economy. However, countries that accommodate higher energy prices with easy money policies soon see energy prices triggering an upward spiral of wages and prices. This was demonstrated when higher oil prices produced much higher inflation in the US than in Germany in the 1970s, reflecting different responses from their central banks.

Since 1982, central banks in North America have downplayed the importance of changes in the money supply, shifting instead to direct inflation targeting. One result of this shift was central banks ignored the inflationary implications of the surge in the money supply during 2021. For example, the Bank of Canada in its quarterly never mentioned rapid money supply growth as a risk factor for inflation. Apparently, central banks no longer heeded one of the fundamental tenets of macroeconomics, Milton Friedman’s aphorism that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

Despite being neglected by central banks, the money supply’s correlation with price movements was restored after 1990 (the persistent gap between the money supply and the CPI, as shown in Figure 2, reflects that money also is used for transactions involving real GDP). While the link between movements in the money supply and the economy may not be precise enough to blindly implement monetarism – one cannot confidently say that an increase of x percent in the money supply will lead to precisely y percent growth in GDP and prices – it is also clear that there is a broad association.

Some economists maintained the money supply continued to provide valuable information. The leading economic indicator produced by Statistics Canada before 2012 and then at MLI always included the money supply because it had one of the best predictive records among its 10 components. In the US, Steve Hanke and Nicholas Hanlon of John Hopkins University, both renowned experts on money and prices, predicted in July 2021 inflation would “be at least 6% and possibly as high as 9%” based on the surge in the money supply (Hanke and Hanlon 2022). As they concluded, “money matters.” Hopefully, the current bout of inflation will lead central banks to agree that money matters when setting policy in the future.

Central bank messaging was unclear

One reason inflation expectations are moving higher is central bank governors were slow to clearly respond to the upturn in prices. What was needed was the sort of clear, uncompromising declaration European Central Bank (ECB) Governor Mario Draghi made in 2012 when he proclaimed “the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough” (Draghi 2012). Instead, in December 2020 the Fed said it would not begin to tighten monetary policy:

until labor markets reached levels consistent with maximum employment and inflation was on track to exceed 2 percent. In its communications the Fed emphasized that both labor market and inflation criteria had to be met to trigger action. As a consequence, while waiting for labor markets to improve further, the Fed kept purchasing assets as inflation gathered momentum, and it kept real interest rates negative even when the economy hit full employment, guaranteeing a substantial overshoot of the inflation target. (Kohn 2022, 2)

The Bank of Canada also was tepid in its initial response, saying inflation would ease to about 2 percent in 2022 as temporary factors dissipated (Bank of Canada 2021, 2).

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem and Fed Chair Jerome Powell recently have taken a more forceful position on inflation. However, they remain reluctant to say major policy mistakes were made during the pandemic. Powell admitted that “it would have been appropriate to move earlier” (quoted in Cassidy 2022), while Macklem acknowledged the Bank of Canada had been too slow to raise interest rates to fight inflation, but adding in his defence that “we got more things right than we got wrong” (quoted in Cross 2022).

Presumably one of the things central banks got right was preventing a return to a 1930s-style depression. The idea the economy was teetering on the brink of a depression is a myth. While the economy plunged when lockdowns of the economy were introduced in March and April 2020, it was also soon obvious that most sectors of the economy quickly adapted to the virus by working from home or installing protective equipment and economy-wide lockdowns were no longer needed. The economy recovered quickly when widespread lockdowns were lifted, after which stimulus was only needed for industries struggling with social distancing rules. This could have been achieved with targeted fiscal programs, not the economy-wide stimulus of monetary policy.

These belated mea culpas from central bankers miss the key point: the priority for a central bank is keeping inflation at its target rate and maintaining financial stability. When it misses the inflation target, it has failed its primary mission and no amount of excuses and hand-waving can subtract from this fundamental miscalculation. Not controlling inflation is the ultimate failure for a central bank. After presiding over the resurgence of inflation in the 1960s, former Fed Chair William Martin bluntly admitted at his farewell luncheon “I’ve failed” (quoted in Timiraos 2022, 33). As for financial stability, it remains to be seen how the financial system will respond to the combination of higher interest rates and the end of quantitative easing that has distorted financial investments for years. It is quite possible a burst of higher inflation will not be the most regrettable legacy of years of easy money policies.

Too many goals for central banks

There is increasing speculation central banks missed their inflation target partly because they are no longer single-mindedly focused on inflation. In recent years, central banks have added goals ranging from fighting climate change to reducing income inequality to their agenda. Indeed, the Bank of Canada recently announced that it was committed to supporting the Indigenous economy (Schembri 2022).

The proliferation of policy goals, in the midst of historically low levels of interest rates and unprecedented increases in central bank balance sheets, is problematic for several reasons. Central banks are poorly equipped to tackle problems such as climate change because they cannot dictate capital flows. Nor is there a pressing need, as “the conclusion of most stress tests is that the impact of climate risk is likely to be moderate” for the financial system (The Economist 2022, 8). Addressing income inequality by helping disadvantaged groups in the labour force requires that central bank run the economy dangerously close to its capacity limit, raising the risk of inflation that contradicts what should be the main goal.

It is not obvious how the Bank of Canada will resolve conflicting priorities. Supporting the Indigenous economy in many parts of Canada means supporting oil and gas development, which contradicts climate change goals. Pursuing the transition to a green economy often means using more expensive renewable energy sources, fuelling what is called “greenflation” as energy prices increase. The conclusion of The Economist special report on central banks “is that a proliferation of aims would interfere with the tasks that only central banks can do” which is control inflation and ensure financial stability (The Economist 2022, 12).

Governments distort the supply response, compounding supply chain issues

Disruptions to supply have played a role in raising prices. This is most evident in areas such as autos where a shortage of semiconductor chips has slowed assemblies (although vehicle shortages also reflect how demand was stoked by low interest rates and rising disposable incomes). However, supply chains played less of a role as inflation accelerated. Most supply issues originate in Canada’s economy, not global supply chains. Statistics Canada’s survey of business conditions in the first quarter of 2022 found only 18.1 percent of firms had problems sourcing supplies from abroad, while 32.1 percent had problems with supplies domestically and even more (37.0 percent) cited labour shortages (Statistics Canada 2022, 2).

Professor John Cochrane of the Hoover Institute criticized the Fed for a simplistic understanding of supply. Cochrane says the Fed focuses only on unemployment “as a measure of slack in the economy. There are no groups of analysts at the Fed measuring how many containers can get through the ports” (quoted in Varadarajan 2022). The unemployment rate, used in the Phillips Curve as a proxy for unused resources, is a poor measure of an economy’s aggregate supply. This was fully revealed during the pandemic, when disruptions to supply were much greater and more complex than suggested by the unemployment rate. Closing down large parts of the economy during the pandemic and sending millions of workers money when leaving the labour force inevitably was going to widely disrupt supply. Cochrane concludes that “The Fed being surprised by supply shocks is as excusable as the Army losing a battle because its leaders are surprised the enemy might attack” (quoted in Varadarajan 2022).

This is not the first time that central banks mistakenly attributed inflation to supply shocks rather than their own actions. In the 1970s, the Fed “believed that the country was experiencing something called ‘cost push’ inflation” as a result of what Fed economist Edward Nelson called “monetary policy neglect” (quoted in Leonard 2022, 61). The result was “the Fed kept its foot on the money pedal through most of the decade because it didn’t understand that more money was creating more inflation” (Leonard 2022, 61).

Some sectors experiencing high inflation have almost no connection to global supply chains. Even the Bank of Canada acknowledges soaring housing prices are mostly the product of surging demand as well as limited availability of land for development. The dysfunction in the labour market also is entirely a domestic issue, as noted earlier, without a counterpart in Europe or Asia where government support during the pandemic was administered much differently than in Canada or the US. Moreover, labour supply problems partly reflect excessive fiscal stimulus, especially in the US where the labour force has shrunk by 500,000 people during the pandemic.

Easy money policies encouraged the neglect of supply

Not focusing on increasing the supply side potential of the economy has been a chronic feature of policy-making since the 2008 financial crisis in most developed nations. Some of this neglect reflects an over-reliance on monetary policy stimulus to cover the growing number of blemishes on the economy’s productive capacity. With demand continually stimulated by low interest rates and ongoing doses of quantitative easing, policy-makers did not feel any urgency to take action to expand supply, such as rolling back regulations, improving the functioning of the housing and labour markets, encouraging business investment, and reducing barriers to inter-provincial trade. The Bank for International Settlements, the central bank for central banks, warned that an excessive reliance on easy money policies was reducing the incentive for reforms that improved supply, concluding “central banks could create time for those fundamental adjustments and reforms to be affected, but could not do more” (Tucker 2018).

Instead of using the opportunity provided by monetary stimulus to expand supply, policy-makers complacently deemed all was well with the economy. As Tucker concluded, the result was “central banks were left as the only game in town” (535). Central banks could have provided incentives for governments to adopt reforms, by tightening monetary policy if governments did not act to increase supply. Central banks could have justified this position by truthfully saying that unrelenting monetary stimulus, without government actions to expand policy, was lowering the economy’s potential growth by, for example, diverting resources from business investment to housing or encouraging governments to run deficits. As noted by former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King, this is the “paradox of policy – in which short-term stimulus to spending takes us further away from the long-term equilibrium” (King 2016, 356).

Conclusion

There are always major consequences when a central bank erroneously assesses an economy’s performance, such as the Bank of Canada’s misjudgment of inflationary pressures building in the economy in 2021. As a result of this error, all Canadians are paying higher prices, many are at risk of losing their jobs in the coming economic slowdown, which is needed to prevent inflation from becoming embedded, while investors risk major losses as the financial system adapts to sharply higher interest rates. As egregious as these losses are, they may be worth it in the long run if this experience refocuses the Bank of Canada and other central banks on their inflation target and the need to monitor the monetary aggregates to keep inflation in check.

About the author

Philip Cross is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Prior to joining MLI, Mr. Cross spent 36 years at Statistics Canada specializing in macroeconomics. He was appointed Chief Economic Analyst in 2008 and was responsible for ensuring quality and coherency of all major economic statistics. During his career, he also wrote the “Current Economic Conditions” section of the Canadian Economic Observer, which provides Statistics Canada’s view of the economy. He is a frequent commentator on the economy and interpreter of Statistics Canada reports for the media and general public. He is also a member of the CD Howe Business Cycle Dating Committee.

References

Bank of Canada. 2020. Monetary Policy Report. July.

Bank of Canada. 2021. Monetary Policy Report. July.

Carmichael, Kevin. 2022. “Poloz predicts inflation will slow quickly over the next 12 months.” National Post, February 25.

Cassidy, John. 2022. “Jerome Powell’s Double Message on Inflation.” The New Yorker, March 17.

Cross, Philip. 2019. Moving Around to Get Ahead: Why Canadians’ Reluctance to Change Jobs Could Be Suppressing Wage Growth. Macdonald-Laurier Institute, December.

Cross, Philip. 2021. Why inflation isn’t transitory and won’t be easily contained. Macdonald-Laurier Institute commentary, November.

Cross, Philip. 2022. “The Bank of Canada has failed, not just Tiff Macklem.” Financial Post, May 20. Available at https://financialpost.com/opinion/philip-cross-the-bank-of-canada-has-failed-not-just-tiff-macklem.

Draghi, Mario. 2012. “Speech to the Global Investment Conference in London, 26 July 2012.” European Central Bank. Available at https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2012/html/sp120726.en.html.

The Economist. 2020. Snapback. The Economist, September 26.

The Economist. 2022. Special Report: Central banks. Too much to do. The Economist, April 23.

El-Erian, Mohamed A. 2016. The Only Game In Town: Central Banks, Instability, and Avoiding the Next Collapse. Random House.

Goldfarb, Sam and Heather Gillers. 2022. “Treasury Hit 3% Milestone.” Wall Street Journal, May 3.

Hanke, Steve H. and Nicholas Hanlon. 2022. “Powell Is Wrong. Printing Money Causes Inflation.” Wall Street Journal, February 24,.

Heaven, Pamela. 2022. “Business confidence slumps to lowest since throes of pandemic.” National Post, April 27.

Jorda, Osca, Celest Liu, Fernanda Nechio, and Fabian Rivera-Reyes. 2022. “Why Is U.S. Inflation Higher than in Other Countries?” FRBSF Economic Letter, March 28.

King, Mervyn. 2016. The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking, and the Future of the Global Economy. W.W. Norton & Co.

Kliesen, Kevin L. and David C. Wheelock. 2021. “Managing a New Policy Framework: Paul Volcker, the St. Louis Fed, and the 1979-82 War on Inflation.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, First Quarter.

Kohn, Donald. 2022. “Two cheers for the Fed.” Brookings Op-Ed, April 27. Available at https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/two-cheers-for-the-fed/.

Leonard, Christopher. 2022. The Lords of Easy Money: How the Federal Reserve Broke the American Economy. Simon & Schuster.

Lowenstein, Roger. 2000. When Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management. Random House.

Macklem, Tiff. 2022. “Opening statement before the Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce.” April 27.

Miller, Rich. 2022. “Jerome Powell faces a tricky path to a soft landing.” Business Week, March 14.

Poloz, Stephen. 2017. “The Meaning of ‘Data Dependence’ An Economic Progress Report.” Remarks to the St. John’s Board of Trade, September 27.

Poloz, Stephen. 2022. The Next Age of Uncertainty. Allen Lane.

Schembri, Lawrence. 2022. “Economic reconciliation: Supporting a return to Indigenous prosperity.” Remarks to National Aboriginal Capital Corporations, May 5.

Statistics Canada. 2022. “Canadian Survey on Business Conditions, first quarter 2022.” The Daily, February 25.

Timiraos, Nick. 2022. Trillion Dollar Triage. Little, Brown & Co.

Tucker, Paul. 2018. “The Only Game in Town: Central Banking as False Hope.” ProMarket, May 14. Available at https://www.promarket.org/2018/05/14/game-town-central-banking-false-hope/.

Varadarajan, Tunku. 2022. “How Government Spending Fuels Inflation.” Wall Street Journal, February 19.

[1] This CPI forecast does not include the change Statistics Canada will soon make to used car prices. Currently, Statistics Canada has a used car component in the CPI but bases its movement on new car prices. Beginning in June, Statistics Canada will measure the actual change in used car prices. The difference could be considerable; in the US, used car prices have risen 35.3 percent versus 12.5 percent for new car prices in the year ending in March, reflecting the shortage of new vehicles.

[2] See Lowenstein (2000) for a history of the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management and Leonard (2022) for the dysfunction in the repo market.

[3] One possible risk arises from the Bank of Japan’s attempt to hold long-term government bond yields at 0.25 percent, which accelerated Japanese investment in US bonds (Japan has surpassed China as the largest holder of US Treasury bonds) and put severe downward pressure on the yen. When the Bank of Japan gives up on its doomed attempt to control domestic bond yields, Japanese investors could leave the US market en masse, putting sudden and unexpected pressure on US interest rates.

[4] Poloz continues to dismiss concerns about inflation as overblown. After the CPI surged 5.1 percent in January 2022, he predicted it would fall below 3 percent by year end because he believed much of the increase was due to lower prices during the pandemic and supply chain disruptions, while touting how monetary stimulus helped avoid “the second Great Depression” (quoted in Carmichael 2022).