Slowing the growth in the health transfer benefits patients and taxpayers, and, yes, even the provinces because it increases the pressure for real health-care reform. And reform, not more federal dollars, is the key to a more sustainable, fairer, and better system.

By Brian Lee Crowley and Sean Speer, Oct. 25, 2016

INTRODUCTION

In the think tank world we spend a lot of time saying the government has got things wrong. This time we are happy to recognise that, at least provisionally, Ottawa got something right, namely their position on health-care funding.

Federal Health Minister Jane Philpott is resisting provincial calls for more federal dollars and instead insisting that the discussion be about reforming how health care is financed and delivered. This is a positive step. The evidence shows that the “system transformation” the minister seeks is needed to improve the affordability, universality, and quality of health care in Canada. She is equally correct that more federal funding would be an impediment rather than catalyst for such reform. That’s why it is so vital the minister and her government continue to resist the temptation to simply throw more money at the problem.

“MORE WITH LESS”? THE FACTS ON FEDERAL HEALTH TRANSFERS AND PROVINCIAL SPENDING

Nothing pleases the provinces more than Ottawa throwing money, however. The provincial and territorial health ministers left their recent meeting with Ms. Philpott lamenting that Ottawa was adopting the Harper government’s longstanding policy that, starting next year, the federal health transfer would increase in lockstep with the growth of the economy, with a guaranteed floor of 3-percent per year.

Unsurprisingly the provinces wanted the old dispensation whereby the Canada Health Transfer grew by 6-percent annually (province-by-province growth can vary). Never mind that the 6-percent escalator was an arbitrary figure or that the previous federal government had given them several years’ notice of the new arrangement. Provincial and territorial ministers arrived at the recent meeting determined to secure more federal funding in order to remove pressure for real reform and thereby avoid “difficult choices.”

Unsurprisingly the provinces wanted the old dispensation whereby the Canada Health Transfer grew by 6-percent annually (province-by-province growth can vary). Never mind that the 6-percent escalator was an arbitrary figure or that the previous federal government had given them several years’ notice of the new arrangement. Provincial and territorial ministers arrived at the recent meeting determined to secure more federal funding in order to remove pressure for real reform and thereby avoid “difficult choices.”

That the transfer is set to increase based on the rate of growth in the economy was a sign of a “declining partnership” according to Ontario’s health minister and would force the provinces to “do more with less” in the eyes of Quebec’s health minister.

Yet the facts about the federal health transfer and provincial and territorial health-care spending tell a different story. Once the provinces knew that Ottawa would slow down the increase in its health transfer, they got to work slowing the rise in their health budgets. They succeeded.

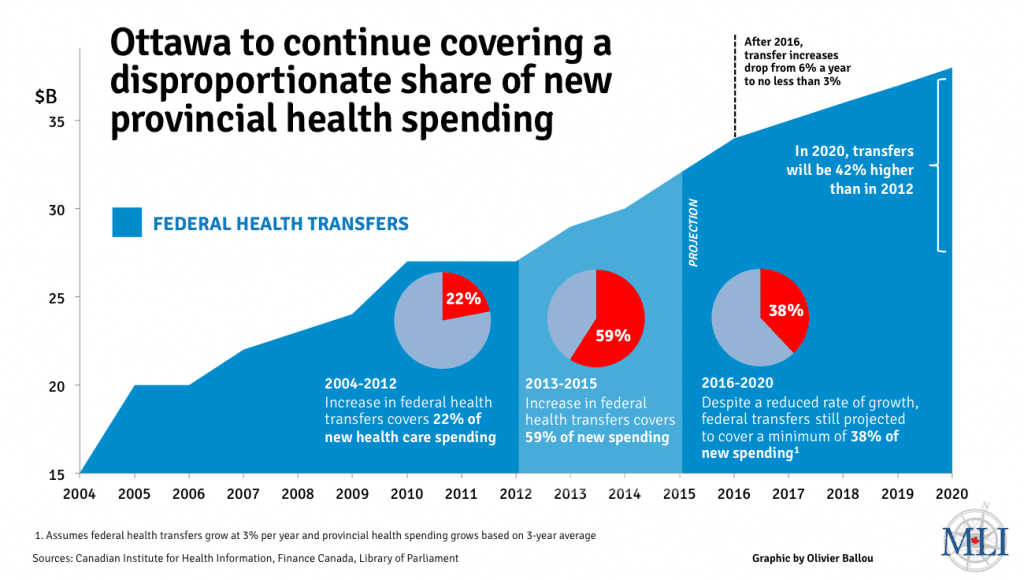

And the result is that not only have the annual increases in the Canada Health Transfer eclipsed the rate of growth of provincial health-care spending in recent years, based on recent trends our projections (see infographic) show that even just the minimum 3-percent growth would cover a significant share of projected annual rises in provincial health-care spending.

Ottawa is presently covering more than 50 cents of every new dollar that provincial and territorial governments put into health care.

Consider Quebec for instance. Between 2012-13 and 2015-16, the province’s federal health transfer payment grew, on average, by five percent annually, while year-over-year health-care spending climbed an average of 2.4 percent. In 2015-16, Ottawa’s health transfer payment to Quebec grew by $424 million while the province’s health-care spending only increased by $160 million. More with less, indeed.

Nor is Quebec particularly unrepresentative of the provinces and territories. Between 2013-14 and 2015-16, annual increases in the federal transfer covered an average of roughly 60 percent of year-over-year increases in provincial and territorial health-care spending. Put differently: Ottawa is presently covering more than 50 cents of every new dollar that provincial and territorial governments put into health care.

If the average growth rate of provincial and territorial health spending remains at today’s level and the Canada Health Transfer grows at 3-percent per year (a very conservative assumption), Ottawa will continue to cover nearly 40 cents of every new dollar in provincial and territorial health-care spending for the next five years. This is no declining partnership – unless of course the provinces plan to let spending rip and want Ottawa to pick up the growing tab.

This is a vital point the federal minister is right to seize on. When Ottawa throws more money in the pot, spending goes up and pressure to reform lessens. By contrast, when Ottawa signals its intention to reduce the rate of growth of its transfer payments, as it did in 2011, the provinces quickly get their spending under control, as they have been doing ever since.

OTTAWA’S ROLE IN CATALYSING REFORM

Which brings us to Ottawa’s role in supporting health-care reform.

Minister Philpott’s focus on “structural reform” to Canadian health care is well-founded. Canada’s health-care system is not only among the most expensive in the world, it performs poorly on a wide range of indicators, including wait times, access to doctors and medical technologies, and the scope of public coverage. There is thus a growing recognition of the need for reform from sources ranging from the Canadian Medical Association to the federal panel on health-care innovation to the Canadian Nurses Association, and virtually everyone in between. Only the most dogmatic medicare activists believe that the status quo is working well.

The question then is: how can Ottawa catalyse reform?

The failure of the 10-year health accord to achieve meaningful improvements highlights the limitations of the federal government to secure reform in exchange for more federal dollars. There are three primary problems with an Ottawa-driven reform agenda.

This is no declining partnership – unless of course the provinces plan to let spending rip and want Ottawa to pick up the growing tab.

The first is that more federal funding simply allows the provinces and territories to defer the tough choices needed to improve the system. Why consider reforms when Ottawa will pay them to maintain the status quo? The result is lost time and poorer outcomes for Canadian patients.

The second is that the federal government has no expertise in administering or delivering health care. The presumption that Ottawa is better placed to set priorities or identify options for reform is belied by the evidence. There is a reason that the federal government has devolved veterans’ hospitals and is co-ordinating First Nations health care with the provinces. Ottawa is not a health-care expert.

The third is that centralizing priority-setting and reform initiatives undermines the potential for provincial experimentation and responsiveness to local circumstances or priorities. There is room for some basic national expectations such as universality and portability but otherwise the provinces and territories are best placed to determine the right priorities for their citizens. One-size-fits-all federal rules ignore differences in demographics, population health, and political predispositions.

The key then is for Ottawa to set the parameters for reform by providing clear, predictable funding and considerable flexibility for provincial and territorial experimentation and reform. Removing legislative prohibitions on extra billing and user fees, for instance, would be a major step to making it easier for provinces and territories to expand public coverage for low- and middle-income citizens in exchange for mean-testing for higher-income earners. But the essential point is that Minister Philpott makes reform more likely when she holds the provinces’ feet to the fire on costs, and removes counterproductive federal obstacles to needed reforms.

The key then is for Ottawa to set the parameters for reform by providing clear, predictable funding and considerable flexibility for provincial and territorial experimentation and reform. Removing legislative prohibitions on extra billing and user fees, for instance, would be a major step to making it easier for provinces and territories to expand public coverage for low- and middle-income citizens in exchange for mean-testing for higher-income earners. But the essential point is that Minister Philpott makes reform more likely when she holds the provinces’ feet to the fire on costs, and removes counterproductive federal obstacles to needed reforms.

CONCLUSION

Last week’s meeting between Minister Philpott and her provincial and territorial counterparts was an important step in the direction of better health policy in Canada. The minister should be lauded for focusing on reform instead of writing larger cheques. The question now is whether she and her government can withstand the invariable criticism from the provinces and territories that will continue to mount. The evidence is on her side. She should hold the line.

Brian Lee Crowley is managing director and Sean Speer is a Munk senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.