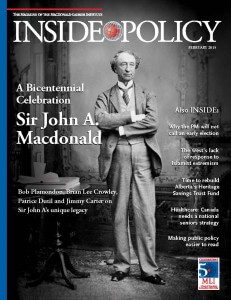

Writing for iPolitics, Ryerson University Professor Patrice Dutil laments that more hasn’t been done to recognize Sir John A. Macdonald’s contributions to Canada.

Dutil says it’s particularly relevant during year of the the bicentennial of Macdonald’s birth, which took place in mid-January.

“The 200th anniversary presented a unique opportunity to address many of the myths that have grown around Macdonald’s memory, but the work has only begun”, writes Dutil.

This item also appears in the February 2015 edition of Inside Policy.

By Patrice Dutil, Feb. 9, 2015

The 200th anniversary of Sir John A. Macdonald’s birth has come and gone. What will Canada make of it?

Macdonald – whose death in 1891 occasioned the largest outpouring of grief in Canadian history and no less than five monuments within four years – has seen his reputation fall on hard times since.

Sure, his portrait has been a feature of the ten dollar bill since 1971 (though the current picture bears little resemblance to the man) and, more recently, Richard Gwyn’s highly readable two-volume biography showed that Canada’s first prime minister had not been entirely forgotten. The experience of the 200th anniversary indicated that there is a light of hope for his memory as he enters his third century.

Here is what is encouraging. A smart policy entrepreneur, for instance, launched a think tank in Ottawa and dedicated it to the memory of Macdonald (and Laurier). A number of books have appeared to discuss Macdonald. Patricia Phenix’s Private Demons: The Tragic Personal Life of John A. Macdonald offered a more intimate look at the man. Ged Martin, the Ireland-based scholar who has penned most thoughtful essays on Macdonald assembled his interpretations in a nifty short biography, John A. Macdonald: Canada’s First Prime Minister, and a probing study of Macdonald in his milieu, Favourite Son? John A. Macdonald and the Voters of Kingston 1841-1891. An important selection of Macdonald’s speeches was assembled by Sarah K. Gibson and Arthur Milnes (Canada Transformed: The Speeches of Sir John A. Macdonald) and a probing collection of essays by historians, co-edited by Roger Hall and I, Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies came out in time for the anniversary.

Even novelists have taken a crack at Macdonald. Roy MacSkimming published Macdonald, Richard Rohmer wrote Sir John A.’s Crusade and Seward’s Magnificent Folly, set in Highclere Castle, the set of Downton Abbey. Roderick Benns wrote The Legends of Lake on the Mountain, a novel for young readers that presents an adventure of a teenage John A. Macdonald.

Dinners were offered in various parts of Canada. The most important one was held in Toronto, with over 450 guests, but others attracted important audiences in Orillia, Ontario (which has been holding these events for decades), the Manitoba Historical Society (which has organized annual Macdonald dinners since the early 1960s) and Hamilton. Not least, Kingston, Ontario was the site of a week-long festival of Macdonald-related events. In Picton, Ontario, a new statue of Macdonald was commissioned by citizens from artist Ruth Abernethy.

Media coverage of the 200th anniversary was fairly good. Among the national papers, the National Post distinguished itself with many essays. According to a recent poll done by Ipsos-Reid for Historica Canada, one in four Canadians still could not identify Sir John A. Macdonald as the first prime minister of the country. This was not a bad result, considering that a similar poll conducted in 2008 showed that 42% of Canadians had no idea who Macdonald was.

The notable absence in the festivities, surely, was Official Ottawa. The Monarchist League has done its bit and MLI is planning to do Macdonald proud at a February soiree, but the federal Canadian Heritage department funded the Kingston Festival and little else. Plans are now afoot to fund Macdonald-related projects, but they are happening more in the context of the upcoming 150th anniversary of Confederation. (The Ipsos-Reid poll found that 28% of Canadians don’t know the year of Confederation and 44% don’t know Canada turns 150 in 2017.)

In striking contrast (even considering scale) has been the decade-long work of the Lincoln Bicentennial of 2009 or, just to give another example, what has taken place in France this summer to honour the 100th anniversary of the murder of Jean Jaurès, the leader of the Socialist party and of pacifism. By those standards, were it not for the efforts of the community, Macdonald’s memory would have been by-passed on this solemn occasion.

Mission accomplished? No. The 200th anniversary presented a unique opportunity to address many of the myths that have grown around Macdonald’s memory, but the work has only begun. More people have to give time, effort and funding to ensuring that Canada’s most significant historical figure and his great contribution — Confederation — is rightfully given his due. At the federal level, funding must be boosted to make historic sites more accessible (during winters, particularly for school children, and on weekends). Demands must be made that the CBC-SRC, which is charged with a public mission, must do more for history. In contrast with its counterparts such as the BBC, PBS or France 2, the CBC-SRC accords nearly none of its budget to historical projects. This situation is intolerable. At the provincial level, governments must do much more to improve the teaching of history. Currently, only four provinces require high school students to take a Canadian history course in order to graduate (Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba and Nova Scotia). It is, quite simply, unbelievable.

The future of Sir John A. Macdonald will depend on what the community makes of his memory. Here are some suggestions.

- Governments and the community fund a Sir John A. Macdonald Centre for the Study of the Nineteenth Century. This would be done efficiently and inexpensively by an alliance of scholars and amateurs. The idea would be to use Macdonald as a lens for his time. Wilfred Laurier did say that the story of Macdonald was the story of Canada, after all. This centre would be tasked with the organization of colloquia, materials in all media and, above all, transcribing the Macdonald papers so that they could be used by scholars, teachers and students across the country.

- Name streets in honour of Sir John A. Macdonald. Until very recently, there were only two streets named to remember Canada’s first prime minister: in Kingston and Saskatoon. Ottawa finally added its name to the roster a few years ago with the Sir John A. Macdonald Parkway, after previously requiring that Macdonald share billing with George-Étienne Cartier. There are “Macdonald” streets across Canada. Why not rename them “Sir John A. Macdonald”? Municipalities with no Macdonald venues should make the effort to change the situation. In Toronto, I have publicly argued that Avenue Road (surely one of the stupidest names ever attributed to an important artery) be renamed in hour of Sir John A. Macdonald. City Council referred the idea to staff, where it was promptly, and quietly, drowned.

- Prime Ministers, Premiers, Mayors and all elected officials should make an effort to recall historic events, Macdonald and people of the “Confederation Generation” in their allocutions and messages. They set the example, and by routinely ignoring events, ideas or the resolve of past generations, they simply show that it is perfectly acceptable to be amnesiac about Canada.

Macdonald’s 200th birthday has shown that individual writers, scholars, and artists in the community can rise to the situation in organizing events and saluting heroes. Governments at all levels, however, must play their parts in helping individuals and communal forces reach more members of the public. Macdonald, who was a careful reader of history, might finally be “at rest” in his grave, as his tombstone proclaims.

Patrice Dutil is a Professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Ryerson University. He is the co-editor, with Roger Hall, of Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies (Dundurn).