This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Bruce Pardy, June 1, 2023

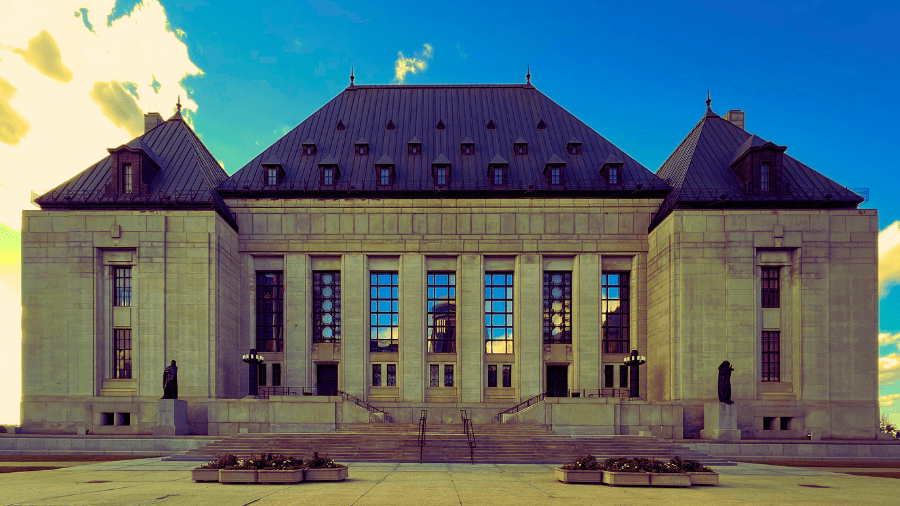

Eighteen years ago, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled Quebec’s prohibition on private medical insurance to be unlawful. Wait times in the public health-care system put people at risk, the majority said, and they have a right to seek private care if the public system can’t deliver. In 2009 a challenge was commenced against similar laws in British Columbia. When the case reached the B.C. Court of Appeal 13 years later in 2022, the court upheld the prohibitions. People can be prevented from obtaining private medical care, the court said, even if waiting in the public system may kill them. In April, the Supreme Court declined to hear the appeal, denying B.C. residents the same rights it earlier gave Quebecers. All good, nothing to see here.

But how can Quebecers have more rights to medical freedom than other Canadians? The Quebec case was not decided under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, but under Quebec’s own Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, a mere provincial statute. Four of seven Supreme Court judges held Quebec’s prohibitions to be inconsistent with this act. Three of those four found that the prohibitions also infringed the Canadian charter, but the fourth didn’t say one way or the other, and the three dissenting judges said no. So the case did not establish that the Quebec law violated the Canadian charter.

Yet the relevant wording in both charters is almost the same. Both guarantee individual rights to life, liberty and personal security. The Canadian charter has one extra phrase. Section 7 says that people cannot be deprived of life, liberty and security “except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” The Quebec provision doesn’t have this clause.

But what, pray tell, are principles of fundamental justice? In previous cases, the Supreme Court has said that a law may deprive Canadians of their right to life, liberty or security of the person as long as it is not arbitrary, overbroad or grossly disproportionate to the law’s purpose. In the BC decision, the majority said the law’s purpose was to ensure that access to necessary medical care “is based on need and not on an individual’s ability to pay.” But what norm applies when the public system can’t or won’t provide medical services in a timely or effective way?

For decades, western nations have experienced a slow cultural revolution. Its intellectual leader, some say, is Marx. Others point to Foucault, Gramsci, or Marcuse. But in the halls of the law schools, its champion must surely be John Rawls. Rawls’ socialist collectivism represents a moral consensus or starting point from which all reasonable people proceed. As Wanjiru Njoya, legal scholar at the University of Exeter, has put it, Rawls’ acolytes rely upon his theories “to defend overtly socialist policies on grounds that such policies are impartial.”

The “veil of ignorance” is Rawls’ most venerated thought experiment. Behind the veil, no one knows their destinies and attributes, such as wealth, abilities, intelligence, race, gender, and so on, or where they will end up in the social pecking order. Since no one is sure whether they will be on top of the heap or at the bottom, the theory goes, every reasonable person would agree that redistribution of wealth and state provision of services are the only rational aspirations.

Of course, the veil of ignorance demonstrates no such thing. My ignorance of the person I will be does not dictate my values. Given the choice between socialism and liberty, I would prefer to be free than managed, and take my chances. But not Rawls’ reasonable person. As Njoya writes, the Rawlsian “favours positive rights and social comforts … guaranteed by the state, which in turn requires a legislative framework designed to implement wealth redistribution.” Like Rawls himself, Rawls’ reasonable man is a socialist.

So, it would seem, are the two B.C. appeal court judges who wrote the majority decision (the third judge concurred in the result). Fundamental justice, they wrote, must be approached “on the basis that no one knows whether they will be among those with sufficient resources (to seek private medical treatment). … If everyone had to choose a distributional principle but did not know if they would turn out to be able to make private provision or not, it is plausible that many or most would opt for a system the protects distribution according to need, rather than ability to pay.” Rawls’ veil of ignorance is not identified by name, but its contours are unmistakable.

Distribution of resources, the judgment concluded, cannot “be held hostage to the veto of any one individual who bears adverse consequences.” In plain English, fundamental justice requires socialized medicine, even if that prevents you from obtaining private care to save your life. The constitution endorses socialism and individual patients be damned. The Supreme Court of Canada is cool with that.

Bruce Pardy is executive director of Rights Probe, professor of law at Queen’s University and senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.