By Philip Cross

August 1, 2023

Executive Summary

Since the recovery from the Covid pandemic started, Canada’s labour market has featured rapid growth in public sector employment. The expansion of government jobs contributed to labour market tightness and contributed significantly to higher government spending and deficits as well as higher prices. The spillover of rising wage rates from the public sector to the private sector risks keeping inflation above the Bank of Canada’s target of 2 percent, requiring interest rates to move higher for longer.

Public sector employment is crowding out the private sector

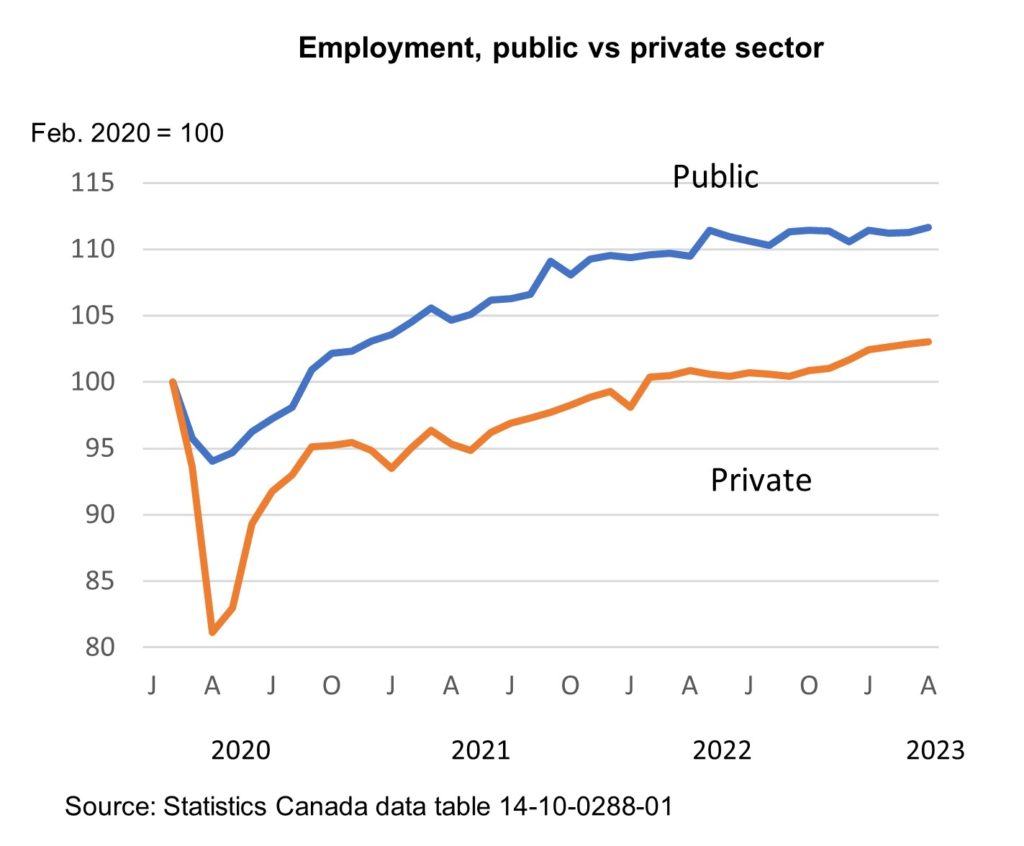

The public sector has dominated the recovery of jobs since the Covid pandemic in 2020 (Figure 1). Between February 2020 and April 2023, public sector employment soared by 11.6 percent,[1] versus a gain of 3 percent in the private sector (which includes both payroll employees and self-employed businesses). In absolute terms, public sector employment accounted for nearly half (48.4 percent) of all jobs added since February 2020 despite accounting for 19.7 percent of all jobs at that time.

Labour demand has outstripped labour supply

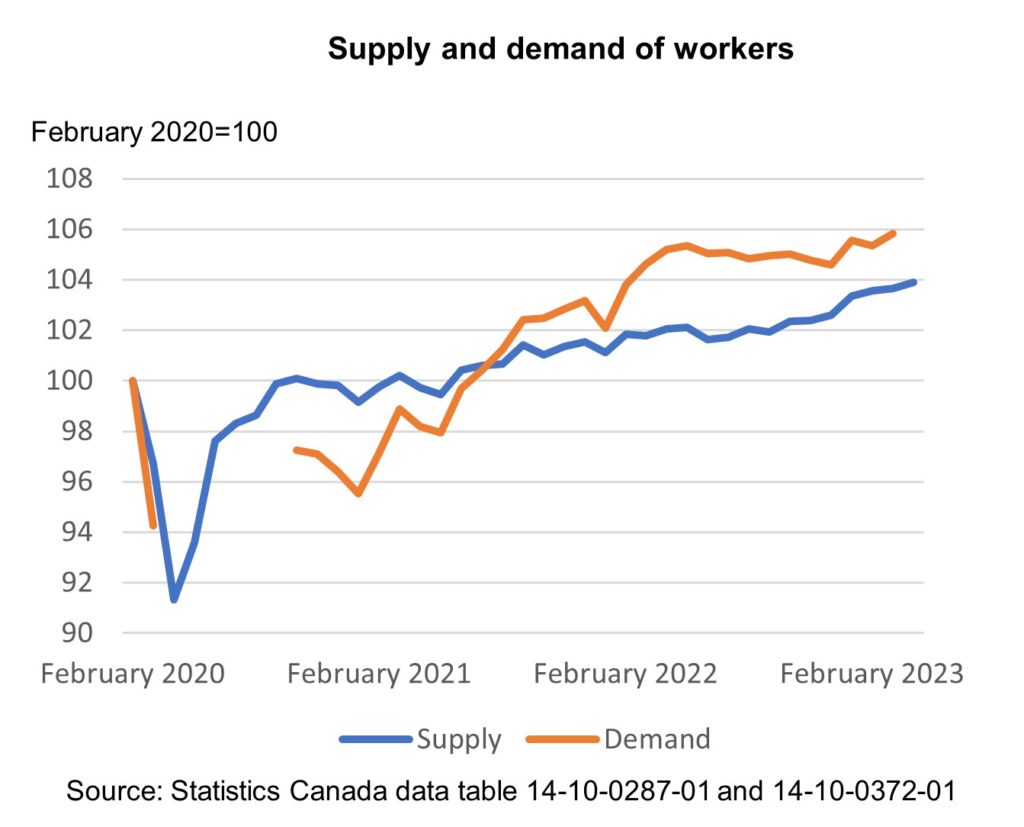

Overall, labour demand in Canada rose by 5.1 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2022. Labour demand is measured by the total of both actual employment (up 3.4 percent since the fourth quarter of 2019) as well as job vacancies, which soared by 68.2 percent during the pandemic (the gap in data for labour demand between April and September 2020 is because data collection was suspended due to the pandemic). Meanwhile, the supply of labour as measured by the labour force grew by 2.8 percent over the same period (Figure 2). The faster growth of labour demand versus labour supply is reflected by record low unemployment and a rapid increase in vacant jobs during the past three years, meeting Statistics Canada’s definition of a labour shortage as “an insufficient number of workers available to fill vacant positions.” (Morissette, 1)

A number of factors constrained the supply of labour during the pandemic. While Canada’s population growth has been the fastest among the G7 nations due to high rates of immigration, the share of adults active in the labour force has fallen slightly. The overall labour force participation rate in May 2023 was 64.5, down from 65.9 in February 2020. Most of the decline was concentrated in people 55 years and older, where the participation rate fell from 38.4 in February 2020 to 37 in May 2023 after rising steadily in the years before the pandemic. Compounding the impact of a lower participation rate, older workers are the fastest growing part of the population in our ageing society. Meanwhile, the participation rate for prime aged people (25 to 54 years old) rose over a full point to 88.7, while for youths 15 to 24 years old it edged down to 64.5.

Vacant jobs have nearly doubled

Historically low unemployment and unprecedented job vacancies have become the most important feature of the recent labour market. With labour demand outstripping the growth of labour supply, the unemployment rate fell to 5 percent, its lowest on record since the labour force survey began in 1976. Meanwhile, the number of vacancies doubled from 508,590 just before the pandemic to over 1 million in mid-2022 before easing slightly to in March 2023, a net increase of 41 percent from its pre-pandemic level (Figure 3). As a result, the job vacancy rate—defined as vacancies as a percent of total demand (employment plus vacant positions)—shot up from 3 percent to a peak of 5.9 percent in mid-2020, before dipping to 4.4 percent early in 2023 (part of that drop is seasonal, as the data on vacancies are not adjusted for the seasonal drop in hiring that occurs every year after Christmas).

Vacancies rose the most in jobs requiring high school or less in educational experience, reflecting shortages were concentrated in industries such accommodation and food and retailing. Conversely, for the graduates of post-secondary institutions that governments prefer in their hiring, there remain more unemployed people than vacancies (Morisette, 1). However, it is also worth noting that job vacancies during the pandemic rose faster for workers with at least some post-secondary education (up 79 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2022) than for people with no post-secondary education (up 67 percent) (Morissette, 4). Meanwhile, unemployment among less educated individuals fell faster during the pandemic (11.2 percent versus 8.2 percent), reflecting the larger increase in vacant positions.

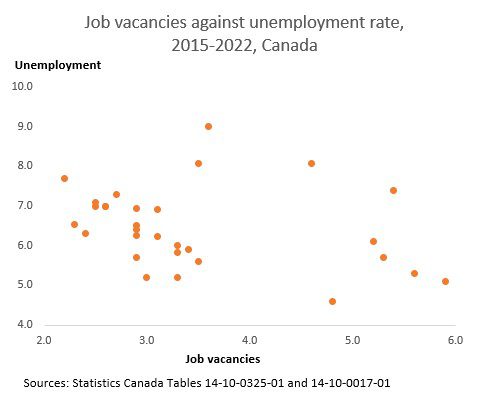

The Beveridge Curve shifts as shortages mushroom

The unprecedented strain in the labour market from low unemployment and high vacancies is reflected in the so-called Beveridge Curve (Figure 3). The Beveridge Curve plots the job vacancy rate versus the unemployment rate over time. For years there was a predictable relationship between particular levels of the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate. However, during the pandemic the Beveridge Curve shifted out radically, as any given level of unemployment was now associated with a much higher vacancy rate. For example, before 2020, an unemployment rate of about 6.5 percent was associated with a vacancy rate of around 3 percent; after 2020, the same unemployment rate was related to a vacancy rate of over 5 percent.

Job Vacancies Against Unemployment Rate, 2015-2022, Canada

A high vacancy rate is one symptom of a shortage of labour while a low vacancy rate is prima facie evidence of a surplus. For all industries, the vacancy rate averaged 4.4 percent in the first quarter of 2023. Vacancy rates remain markedly lower in most of the public sector. The vacancy rate in government industries were below-average in education (1.5 percent), utilities (2.2 percent) and in public administration (2.7 percent). Health care was the only public sector industry with an above-average vacancy rate (of 6.1 percent). Unemployment in all of the public sector was below-average in April 2023, ranging from 2.9 percent in health care to 1.7 percent in both education and public administration. The implication is that the unemployment rate and the vacancy rate remained low in the public sector outside of health care. Most of the outward shift of the Beveridge Curve in Figure 3 was due to higher vacancies in the private sector.

Low vacancy rates allowed governments to rapidly increase employment between February 2020 and May 2023. All government industries substantially expanded employment during the pandemic, with gains of 18.3 percent in public administration, 10.4 percent in education, and 4.9 percent in health care (health care was the only public sector where growth was restrained by shortages of labour).

The health care industry’s high vacancy rate reflects the difficulties of finding and retaining workers during the Covid pandemic. The vacancy rate for health care was 3 percent just before the pandemic began, matching the average for all industries. Since then the vacancy rate for health care has doubled to 6.1 percent, twice the economy-wide rate of increase. However, as the pandemic recedes amid central bank tightening, the health care industry should find it easier to attract and keep its work force. Education and public administration have long had below-average vacancy rates (averaging 1.0 percent and 1.6 percent respectively just before the pandemic), reflecting how the industry’s high rates of pay and other benefits have always attracted an ample supply of labour to these government institutions.

Meanwhile, vacancies have soared in a number of private-sector industries. The highest vacancy rates early in 2023 were in construction, administration, accommodation, and food. There also were numerous vacancies in manufacturing, professional services, and retailing. Finance, insurance and real estate was the only private sector industry with vacancy rates as low as the public sector, reflecting the boom in Canada’s housing market at a time of record low interest rates and high immigration.

Most private sector employers cannot match the pay and benefits offered by governments. While governments can fund themselves with taxpayer dollars and the seemingly endless amount of debt issued (most of which was purchased by the Bank of Canada during the pandemic to keep the cost of borrowing low), private-sector firms are constrained by the need to keep costs and prices competitive and maintain healthy balance sheets.

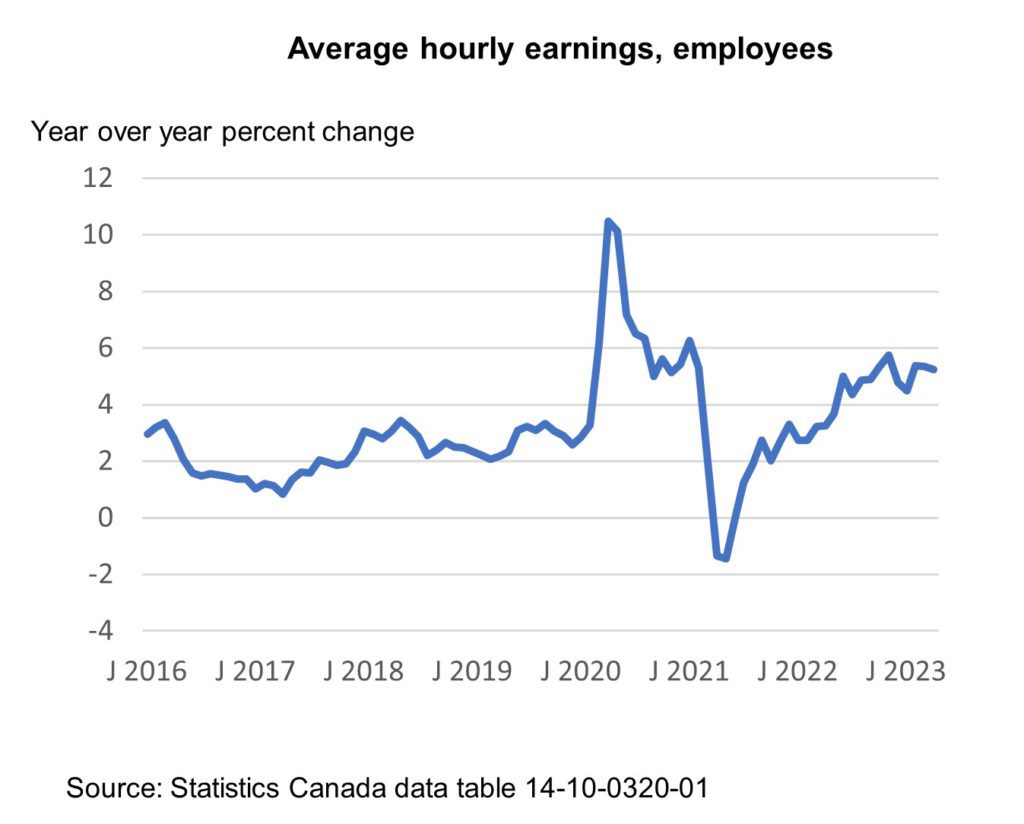

Higher vacancy rates and labour market tightness clearly are putting upward pressure on wages. In the fourth quarter of 2022, employers increased the hourly wage they offered for vacant positions to $24.90, up 8.5 percent from a year earlier. By comparison, wages for all employees rose 5.3 percent (Statistics Canada, The Daily, 2023).

Generous pay and benefits in the public sector attract workers

One reason vacancy rates usually are so low in the public sector is the high level of salaries and other benefits. Salaries in Canada’s public sector exceed comparable jobs in the private sector by 10 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Abdallah et al, 10). This exceeds the 5.2 percent average for all advanced market economies. Public sector workers also enjoy greater job security, more generous sick leave provisions,[2] and higher pension benefits.

Helped by historically low vacancy rates entering the pandemic, the public sector was able to substantially increase its payrolls during the pandemic. The attraction of employment in the public sector was heightened during the pandemic by greater job security and its ability to offer work-from-home on top of its higher pecuniary benefits. Employment in the government sector fell by less than half the rate of the private sector at the worst of the pandemic, and recovered three times as fast. Despite the ease with which the public sector was able to expand its labour force and keep vacancy rates low (outside of health care), managers never sought to cut compensation for those working at home as the private sector did.

The federal Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) recently published a report detailing the explosive growth of both employment and compensation in the federal government during the pandemic. Total spending on personnel jumped by 30.9 percent between fiscal 2019-20 and 2021-22: “This represents average annual growth of 14.4 per cent, well above the historical average growth of 3.4 per cent observed over 2007-08 to 2019-20” according to the PBO (6).

The federal public service expanded by 8.2 percent between fiscal 2019-20 and 2021-22 in terms of full-time equivalents (PBO, 1). This average annual increase of 4 percent exceeded the historical average of 1 percent in the preceding dozen years (PBO, 7). The surge of government employment cannot be dismissed as solely related to the pandemic or a growing population. The PBO’s analysis shows that the number of federal employees per Canadian has been rising steadily since the election of the Trudeau government in 2015, after falling during the austerity of the Harper government (PBO, 8).

Over the same period, average compensation per federal employee rose from $117,497 to $125,300, an increase of 6.6 percent. This annual average increase of 3.3 percent compares with an average gain of 2 percent between 2007-08 and 2019-20 (PBO, 1). Salaries represent the largest part of personnel spending at 61.7 percent, followed by pensions (9.9 percent), overtime and bonuses (4.1 percent) and other payments. All components of compensation rose at above-average rates during the past two years.

Higher pay for government employees made a significant contribution to the growth of government spending and deficits since the pandemic began. Between 2019 and 2022, compensation of employees in public administration, education and health care rose by 16.2 percent, an average of 5.4 percent a year (Statistics Canada). One-third of the increase reflected the growing ranks of public employees, and two-thirds higher compensation. The total increase in compensation cost $54.8 billion, which represents one-quarter of the increase in government spending over the last three years.

Public sector pay raises private sector wages and inflation

Higher public-sector pay fuels inflation through at least two mechanisms identified by the IMF. One is raising inflationary expectations because “an increase in public wages that leads to an increase in the value of debt can be inflationary if investors believe the government will not accumulate the surpluses needed to repay it or that they require a higher return to hold such debt” (Abdallah et al, 21). The second is “is potentially through their impact on affecting the likelihood and the severity of an economy-wide wage-price spiral… For example, when large and powerful public sector labour unions negotiate higher wages, these can have important spillover effects on private sector wages and result in price inflation” (Abdallah et al, 21).

In turn, the IMF identified two mechanisms by which “private sector wages and inflation respond positively to changes in public wage.” (Abdallah et al, 2). High public-sector wages can help push up private-sector wages directly by setting a precedent for private-sector unions to match their increases (this is less likely in Canada where unionization outside of the public sector is low). Indirectly, attracting workers to the public sector in sufficient numbers helps create a labour shortage for the private sector, forcing employers to increase wages to attract or retain workers. In Canada’s current context of the highest inflation rate since the 1980s, the upward pressure that rising public-sector wages put on private-sector wages increases the possibility of a wage-price spiral.

The inevitable result of a tighter labour market and a scarcity of workers is higher wages. In the last 12 months, average hourly earnings rose 5.2 percent, up from 3.3 percent in the previous year according to the labour force survey, and the greatest increase since December 2006 (outside of 2020 when average wages were distorted by larger job losses among lower-paid workers) (Figure 4). Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem acknowledged in May 2023 that “Most wage growth measures remain around the 4% to 5% range” and that “persistent wage growth in that range will make it difficult to achieve the 2% inflation target” (Macklem, 2).

Higher wages put upward pressure on prices, since labour is the single largest cost for employers. This is especially true for services, which mostly rely on domestic sources of labour to produce their product. It is not coincidental that, as wage costs have accelerated over the past year, inflationary pressures in the CPI shifted from goods to services, where prices in the latest 12 months rose faster than for goods (4.8 percent versus 4.4 percent). As higher wage costs persist, it will become more difficult for the Bank of Canada to make further gains in lowering inflation to its target of 2 percent. As inflation remains above target, the Bank of Canada will have to maintain interest rates higher and for longer.

Recent deals granting members of the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) a 12.6 percent raise over four years and Montreal police 20 percent over five years will put further upward pressure on wages in other industries.[3] One human resources expert observed of the PSAC deal that “private sector employers will have to match that to have any prospect of attracting or retaining employees” (Levitt). This continues a recent trend of higher negotiated wage settlements in the public sector than the private sector, with settlements averaging 3.7 percent and 3.1 percent in the public sector over the last two quarters respectively. Already, private-sector settlements show an upward trend, although not as pronounced as in the public sector, with increases averaging 2.9 percent in the two most recent quarters versus 2.6 percent in the previous year.

Governments clearly are aware of how bidding up the wages of public servants can increase the cost of labour for other employers competing for a limited supply of workers. Some governments even complain about higher wages offered by other levels of government. In a recent interview, Quebec Premier Francois Legault complained that municipal governments in Quebec “are paying 30 percent more for the same jobs as the Quebec government”[4] (Krol).

Conclusion

The rapid growth of government employment and wages undermines Canada’s long-term economic growth in several ways. It has contributed to the rapid growth of government deficits and helps prevent the return to a balanced budget. The rapid growth of labour demand by governments also helped tighten the overall labour market, helping lower unemployment and raise vacancy rates. Tight labour markets put upward pressure on wages and prices, complicating the Bank of Canada’s efforts to return inflation to its target rate of 2 percent. Most insidiously, the rapid growth of government has shifted resources away from more productive uses in the private sector, helping to perpetuate the economic stagnation that has gripped Canada over the past decade.

References

Abdallah, Chadi, David Coady and La-Bhus Fah Jirasavetakul. Public-Private Wage Differentials and Interactions Across Countries and Time. International Monetary Fund, WP/23/64. March 2023.

Cross, Philip. A Sickness in the System: How Public Sector Use of Sick Leave Benefits Really Compares to the Private Sector. The Macdonald-Laurier Institute, November 27, 2015.

Krol, Ariane. Les municipalités devront mettre la main à la poche, prévient Legault. La Presse, le 20 mai, 2023.

Levitt, Howard. PSAC strike deal will cast long shadow. Financial Post, May 20, 2023.

Macintyre, Patrick. Le nombre de postes vacants a atteint un sommet en 2022. La Presse, le 10 juin, 2023.

Macklem, Tiff. Staying the course to price stability. Remarks to the Toronto Region Board of Trade, May 4, 2023.

Morissette, Rene. Unemployment and job vacancies by education, 2016 to 2022. Economic and Social Reports. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001, Vol. 3, no. 5, May 2023.

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Personnel Expenditure Analysis: Update. April 4, 2023.

Statistics Canada. Survey of employment, payrolls and hours. The Daily, March 21, 2023.

Statistics Canada. Table 36-10-0489-04. Compensation by NAICS industry.

[1] This is very close to the 9.2 percent total increase for education, health care and public administration employment. The latter three industries are used as a measure of the public sector when data for the latter are not available.

[2] For more on sick leave benefits in government, see Cross (2015).

[3] The increase for Montreal policy can be justified by high vacancies, which have grown nearly 60 percent since the 2010s to reach 529 despite 207 new hires in 2022. (Macintyre)

[4] Translation by the author of the original quote “Les municipalités, en moyenne, payent leurs employés 30% de plus que pour les mêmes postes qu’on a au gouvernement du Québec.” (Krol)