This article originally appeared in the Hill Times.

By Donald J. Savoie, December 30, 2024

Canada’s Constitution is a combination of codified acts and unwritten rules known as constitutional conventions. The codified parts provide an unambiguous legal framework for the exercise of power. The uncodified parts are less clear and, at times, open to interpretation. The relationship between the prime minister and the governor general is guided by constitutional conventions as is the relationship between the prime minister and cabinet. Constitutional conventions provide a level of flexibility that a fully codified Constitution does not.

Constitutional convention stipulates that the Governor General exercises her powers, “almost without exception” on the advice of the prime minister. It is not clear what constitutes, almost without exception, or what could prompt the governor general to exercise her power while ignoring the advice of the prime minister. The almost-without exception has never been defined or properly tested. It will be recalled that governor general Lord Byng ignored the advice of prime minister Mackenzie King to dissolve Parliament. King made it an issue in the subsequent election and won. No governor general since then has refused to act on the advice of prime ministers.

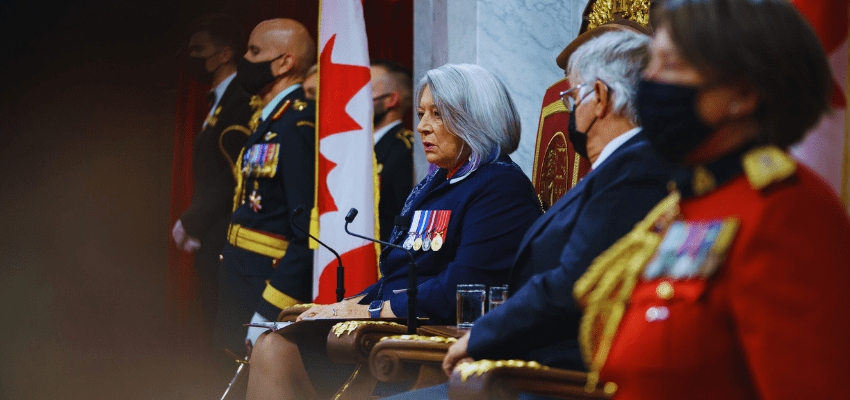

Gov. Gen. Mary Simon would be on solid ground in dismissing the advice from the leader of the opposition to recall Parliament. If she must decide from whom she should take advice between the prime minister and the leader of the opposition, the decision is as clear as if it were guided by a codified clause in the Constitution: the prime minister. If she were to decide to take the advice of the leader of the opposition, where would it end or how would she decide on which issues the prime minister’s advice should prevail over that of the leader of the opposition? The way for the Governor General to be above partisan politics is not to become partisan by pitting the advice from the prime minister against the advice of the leader of the opposition.

However, what if the leader of the opposition would ask all Members of the House of Commons to co-sign a letter asking the Governor General to reconvene Parliament or for her to refuse a request from the prime minister to prorogue Parliament? And what if over 50 per cent of the Members of the Commons agreed to sign the letter? Members of Parliament making a formal request in a letter carries more weight than individual MPs issuing a press release or giving an interview to journalists. The Governor General would then have to decide if such a letter signed by a majority of MPs qualifies under the “almost without exception.” The advice to the Governor General would be coming from a majority of MPs in the Commons, not from the leader of opposition.

Much has been said lately about the growing power of the prime minister and the ability of prime ministers to govern from the centre. Without putting too fine a point on it, they have been able to govern from the centre because the role and powers of prime ministers have been shaped by constitutional conventions. Much has also been said about Parliament losing influence and credibility. Former Members of Parliament have made the point that Parliament is now about political theatre and little else.

Today, under the Westminster parliamentary system, power should lie in the hands of the King in Parliament, not in the hands of the King and prime minister. At the moment, the decision to prorogue Parliament or to recall Parliament lies in the hands of the government, or more to the point, in the hands of prime ministers. One way to rebalance power between prime ministers and Parliament is to give Parliament the power to decide when it should sit. Members of the House of Commons who do not sit on the government side of the House can only request a recall of Parliament through the government and if the government should refuse, MPs have no other course of action. It only stands to reason that if a majority of MPs want the Commons to sit, then they should have the power to make that decision.

Giving the power to a majority of MPs to decide when they meet would go some distance in giving Parliament some power over the government of the day. More would be required to give Parliament credibility in the eyes of Canadians, but it would be a start.

Donald J. Savoie is the Canada Research Chair (Tier 1) in public administration and governance Université de Moncton.