By Josef Filipowicz and Steve Lafleur

March 30, 2023

Introduction

Canadians are increasingly worried about housing affordability. This issue featured among voters’ top concerns in recent federal, provincial and local elections, prompting an emerging suite of policy responses. What’s often overlooked is how policies from all levels of government interact. Policies from one level of government might conflict with policies from another. This report expands on one such incongruence: the disconnect between policies affecting population growth – and thus housing demand – and growth planning policies, which guide housing supply.

The first section of this report presents the wide, growing gap between population growth (one measure of housing demand) and housing completions (one measure of housing supply). The second section examines immigration, the primary source of population growth in Canada, as well as the policy mechanisms used to determine immigration levels. Notably, housing supply constraints do not feature as a consideration in the federal-provincial/territorial agreements informing eventual decisions on the number of immigrants to admit in the near-term. The third section focuses on housing supply, by highlighting three key issues with growth planning policies and processes – namely, growth planning is often lengthy, not reflective of the magnitude of demand, and poorly enforced.

The final section highlights some of the consequences associated with the resulting mismatch between housing demand and supply, as well as potential solutions. To improve the overall coherence of Canada’s housing policies, the federal government could amend current immigration-related legislation, requiring consultation with provinces and territories to include more robust consideration of housing supply constraints. Concurrently, provinces and territories could speed up growth planning by reducing the length or number of steps between plan design and implementation; making growth planning more accurate by better aligning it with immigration policy (and resulting population growth); and improving implementation by more actively enforcing growth planning targets. Finally, provincial and federal governments could incentivize municipalities to allow more housing construction.

The problem: Homebuilding is not keeping up with population growth

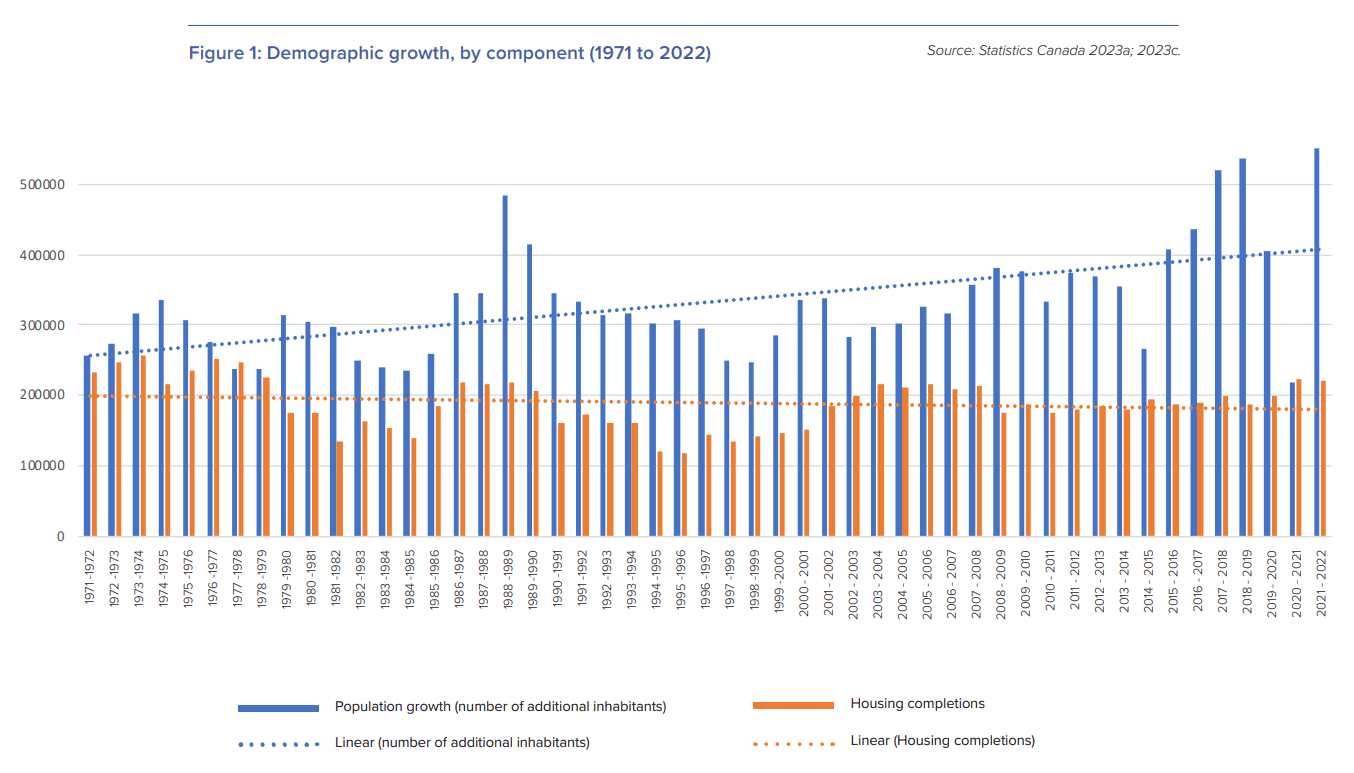

At its heart, Canada’s housing affordability crisis is primarily driven by a large, growing gap between supply and demand. In other words, there is a mismatch between the number of homes available to rent or buy and the number of households (individuals and families) seeking to rent or buy them. A growing body of literature identifies this gap,[1] and Figure 1 illustrates it by comparing population growth and housing completions in Canada since the 1970s.

Annual population growth (blue) represents one measure of housing demand. Though the number of additional inhabitants varies from year-to-year, the trendline indicates a steady increase from under 300,000 per year in the 1970s to just under 400,000, on average, in the most recent decade. The sharp decline in population growth from 2020 to 2021 reflects the COVID-19 era border closures, which have since been lifted, allowing the resumption of robust population growth and resulting demand for housing.

Annual housing completions (orange) represent one measure of the housing supply. The comparison of individual years, as well as the trend line indicate that annual housing completions declined, on average, since the 1970s, when housing completions routinely exceeded 200,000 units per year. This rate of homebuilding is notable not just because it has remained unmatched since, but because Canada’s population was approximately one-third smaller than it was in the most recent decade.

As these dual trends suggest, there is a growing gap between housing demand (population growth) and supply (completions). Further, this problem is compounded by decades of underbuilding. In short, this is not a new problem; it has worsened as housing completions waned and population growth increased.

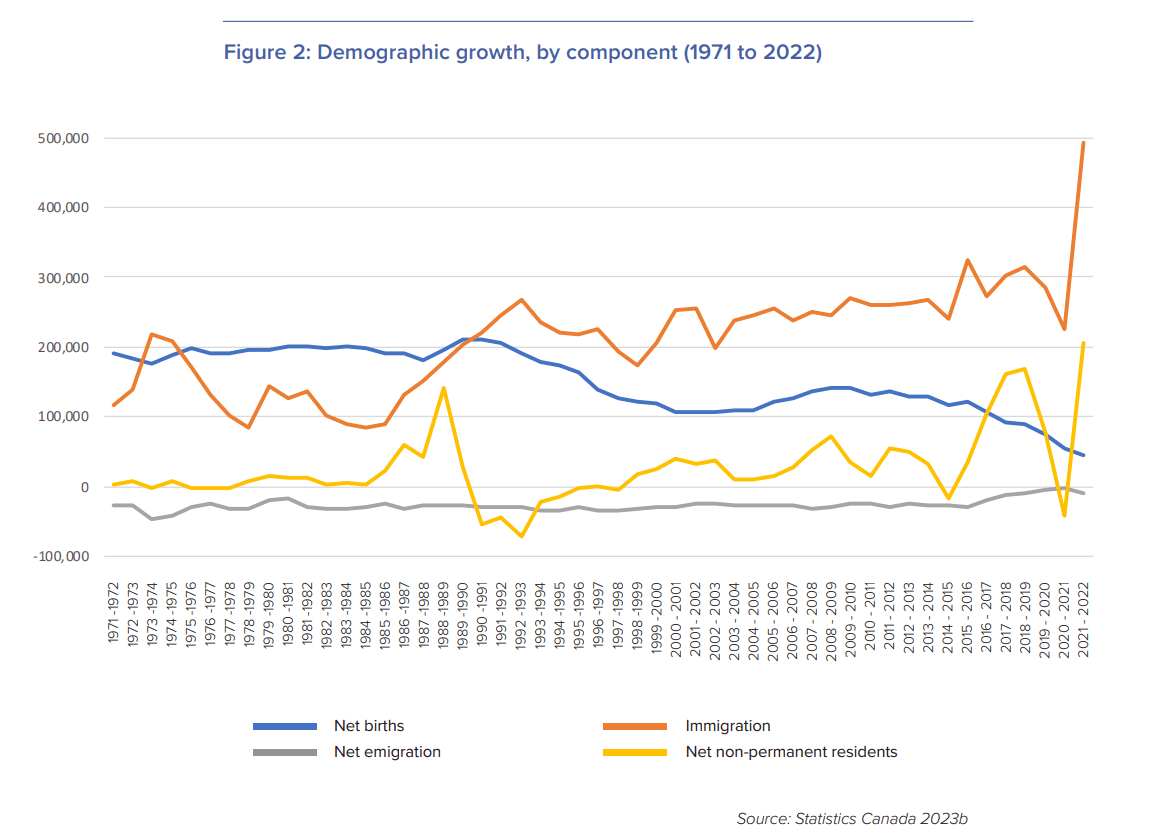

Demand: Decisions about immigration do not adequately account for housing supply constraints

Canada’s population growth – a major driver of housing demand – consists of several components. As shown in Figure 2, these include net births (births minus deaths), immigration,[2] net emigration (emigrants minus returning emigrants), and net non-permanent residents.[3] Since the 1990s, immigration replaced net births as the primary driver of population growth, followed by net non-permanent residents since the 2010s. Unlike birth rates, which governments can only indirectly influence, immigration and non-permanent residency are both within the purview of the federal, and, to an extent, provincial governments.

The federal government is statutorily required to establish annual Immigration Levels Plans, which determine, among other goals, the target number of immigrants admitted in the near term.[4] The most recent Immigration Levels Plan, published in November 2022, targets 465,000 permanent resident admissions in 2023, 485,000 in 2024, and 500,000 in 2025, the highest in Canada’s history (Government of Canada 2022c).

Though produced by the federal government, provincial and territorial government input is required for the elaboration of Immigration Level Plans, while some municipal governments also participate in consultations. This input is summarized in a series of federal-provincial/territorial agreements, which are periodically updated.[5] For example, the Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement, created in 2017 (and extended in 2022), defines the roles and responsibilities each level of government has in the accompaniment of immigrants, as well as demographic, educational and labour market needs (Government of Canada 2017).

Perhaps surprisingly, none of the agreements signed with provinces or territories directly mention housing. Adjacent terms, such as access to settlement “services,” “activities,” or “requirements” are mentioned, implying a possible link, but none explicitly mention the need for quantitatively or qualitatively adequate housing supply. Only one ancillary agreement, the Canada-Ontario-Toronto Memorandum of Understanding on Immigration, from 2018, mentions a commitment to “discuss access to services, including settlement and other supports, such as housing, education and health” (Government of Canada 2018).

Considering the role these consultations and agreements play in the development of immigration policy, including Immigration Levels Plans, federal and provincial policy-makers should consider the consequences of not adequately aligning population growth targets with housing supply indicators.

Some provincial leaders have started expressing concern regarding this misalignment. In a November 2022 press conference, Ontario Premier Doug Ford cited the need to reconcile increased immigration targets with homebuilding capacity (Government of Ontario 2022). British Columbia Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon was more prescriptive, calling on the federal government in January 2023 to “actually tie immigration numbers to affordable housing targets and as well as new housing starts” (Zussman 2023). Though not reflected in the wording of the most recent Immigration Levels Plan, these sentiments suggest an emerging awareness of the important link between immigration policy and housing supply systems.

Supply: Growth planning is lengthy, poorly anticipates demand, and is poorly enforced

Faced with high and rising demand for housing, growth planning has not kept pace. Specifically, the systems by which provincial and local governments estimate housing needs and plan for growth have neither adequately anticipated the magnitude of housing demand, nor enforced existing (inadequate) targets. Three specific, interrelated shortcomings are at play.

Growth planning is lengthy

First, growth planning processes take a long time. For example, the Ontario government updated its Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe in 2019, with further amendments in 2020 (Government of Ontario 2020). This plan, which guides how Toronto and its surrounding region will grow in subsequent decades, and presents numeric growth targets in the form of households and businesses, was initially introduced in 2006 (Ontario Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal 2006). In turn, all municipalities within the Greater Golden Horseshoe region were given until 2022 to update their official plans (which provide more granular guides on how communities plan to grow) to reflect the changes to the provincial growth plan.

Similarly, the City of Vancouver – which previously did not have a citywide official plan – started work on its Vancouver Plan in 2019, leading to approval and implementation in 2022 (City of Vancouver 2022). As a 30-year plan, the Vancouver Plan also commits to aligning with an overarching regional growth strategy, Metro Vancouver’s Metro 2050 (Metro Vancouver, 2022). These estimates, in turn, guide other forms of growth-related capacity planning, from transportation to sewer and water systems.

As these examples from Ontario and British Columbia illustrate, the processes guiding how much housing gets built and where can take years and apply for very long periods after being enacted. There are well-intentioned reasons for such timelines, such as the willingness and responsibility to engage with residents, as well as the provision of long-term infrastructure. However, the length of time required to produce these plans, as well as more “downstream” implementation such as local zoning bylaw updates, creates a substantial delay between the decisions with the most influence on housing demand (federal-provincial/territorial immigration targeting) and the decisions with the most influence on housing supply (local and regional growth planning).

Growth planning poorly anticipates demand

Second, growth planning processes do not adequately reflect the magnitude of demand, both in the short-term and especially in the long-term. As time-limited policies aimed at accommodating anticipated growth, growth plans require assumptions regarding housing demand. These typically come in the form of projections estimating the number of additional inhabitants and/or households a city or region will need to house by a specific end date.

In the Ontario example, the initial Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, from 2006, included estimates of population and job growth every decade until 2031. These estimates were revised in the 2020 update to the Growth Plan, which extends projections to 2051 (Government of Ontario 2020). The Vancouver Plan, as with Metro Vancouver’s regional growth strategy, include projections to 2050 (Metro Vancouver 2022).

Long-term planning is valuable, especially from the perspective of infrastructure provision. Long-lived assets such as sewers and water infrastructure require foresight, including both the location and magnitude of growth. However, if the growth estimates informing them are based on growth rates, policies and assumptions from one particular period, they are unlikely to adequately anticipate changes in subsequent periods. Notably, the rapid increase in population growth established by the most recent Immigration Levels Plans was announced after both the Greater Golden Horseshoe and Metro Vancouver targets were determined.

Considering the outsized role these two regions play as Canada’s primary ports of entry for immigrants, growth plans’ inability to incorporate subsequent major changes in immigration policy undermines these plans’ effectiveness, and ultimately contribute to worsening the gap between housing demand and supply (Statistics Canada 2022b).

Growth planning is poorly enforced

Third, in those cities and regions where growth projections or targets exist and directly inform growth planning, they remain largely unenforced. Many growth plans include some form of performance monitoring, such as changes in land-use designations to accommodate planned growth, or simple tracking of population or household growth. However, few include formal mechanisms by which to redress lagging performance.

For example, the 2006 version of Ontario’s Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe projected that the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (the Greater Golden Horseshoe’s contiguous urban core) would reach a population of 7,770,000 inhabitants by 2021, implying that housing and infrastructure capacity should evolve accordingly. However, the 2021 census reported a total population of just over 7,280,000 inhabitants – almost half a million fewer than anticipated (Statistics Canada 2022a).

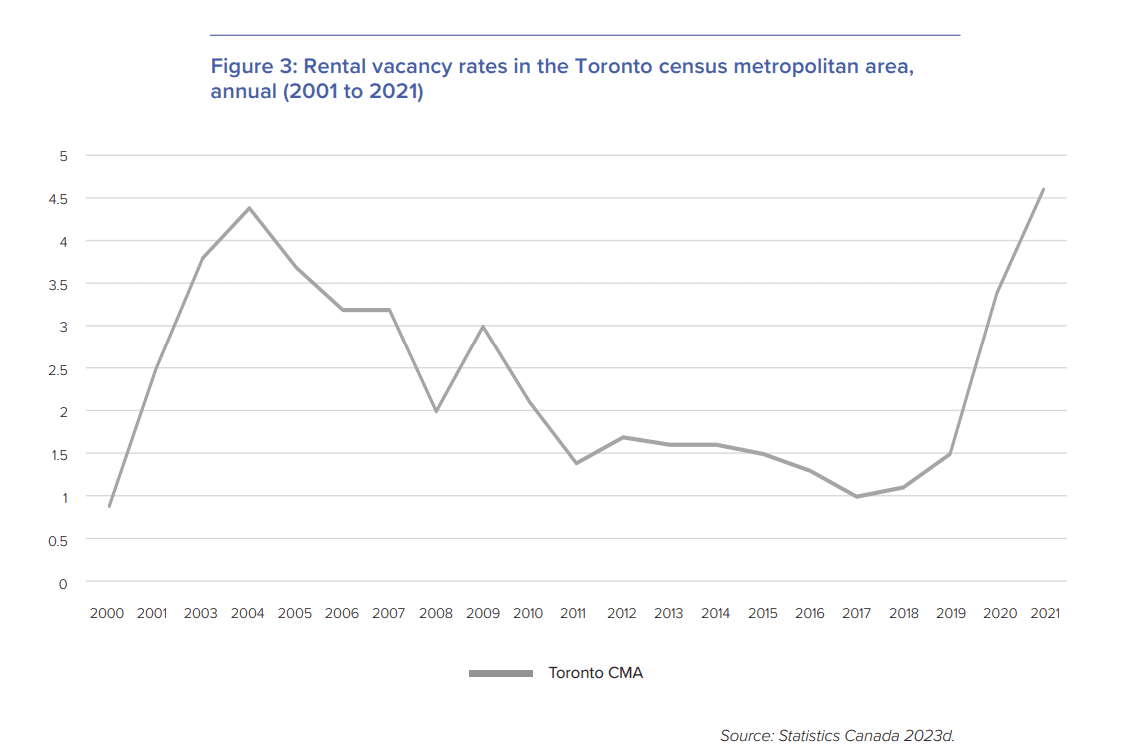

Rather than indicating a lack of demand or growth pressures, this gap between projected and actual growth is likely more indicative of lagging or inadequate housing supply. As shown in Figure 3, the Toronto census metropolitan area’s (CMA) rental vacancy rates – an important gauge of housing availability – has fallen progressively over the three most recent decades, barring a temporary reversal during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.[6] This trend indicates, among other things, a steadily decreasing capacity to accommodate housing demand rather than a reduction or saturation in demand itself, which would manifest itself though higher rental vacancy rates.

Increasingly aware of this discrepancy (between supply and demand), the Ontario government announced a new set of housing targets in October 2022. These targets, which were determined for 29 cities, were informed by the government’s new goal to build 1.5 million homes by 2030 – roughly twice as many as would be built based on recent building rates. Similarly, the government of British Columbia has announced the intention of establishing similar municipal-level targets in upcoming legislation (Government of British Columbia 2022). In both cases, however, no mechanism ensuring these targets are met was announced.

Consequences and solutions

Consequences

Many Canadian communities have become severely unaffordable to a growing share of residents earning local incomes. Not only does Canada have the largest gap between home prices and incomes among G7 nations (OECD 2023), but shelter costs writ large have steadily eroded earnings in most Canadian cities in recent decades (Filipowicz, Globerman, and Emes 2020). All levels of government are facing mounting pressure to address this issue, including its many symptoms.

Indeed, failing to close the demand-supply gap in housing has widespread consequences for Canadians’ personal and economic well-being. The direct impacts of eroding affordability are higher rents and home ownership costs, which hurt low-income individuals and families the most, but also first-time buyers or growing families in search of more living space.

Less directly, high housing costs hamper workers’ ability to move in search of higher-paid, more productive work. This phenomenon, labelled “spatial misallocation” by economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, is not only harmful to individual advancement, but is estimated to have lowered aggregate US GDP growth by 36 percent from 1964 to 2009 (Hsieh and Moretti 2019). Similar analysis has yet to be published in Canada, but there is little reason to believe similar economic consequences have not afflicted it, especially considering the poorer income-to-shelter cost ratios typically found in Canadian communities relative to their US counterparts (Filipowicz, Globerman, and Emes 2020).

Related to economic growth, immigration policy can also be hampered by housing affordability challenges. Faced with high (and rising) rents and home prices, recent and prospective immigrants may have trouble establishing themselves in Canada, or may forego immigration altogether. For example, international applicants for Canadian study permits must provide proof they have $10,000 beyond the costs of tuition, a sum meant to represent the “Minimum funds needed to support yourself as a student” for one year (Government of Canada,2023). This sum implies a minimum monthly cost of $833 for all non-tuition expenses, such as rent, food and transportation. In many (if not most) Canadian regions, this sum is well below actual costs, especially rents. According to recent estimates, three-bedroom units – offering the lowest-cost option for students sharing them as roommates – average $2323 ($774 per bedroom) per month nationwide, $2842 ($947 per bedroom) in Ontario, and $3298 ($1099 per bedroom) in British Columbia (Urbanation 2023). Faced with such large discrepancies, many applicants may reconsider, or avoid applying altogether, in turn undermining the goals of immigration policy, such as growing Canada’s pool of skilled labour.

Solutions

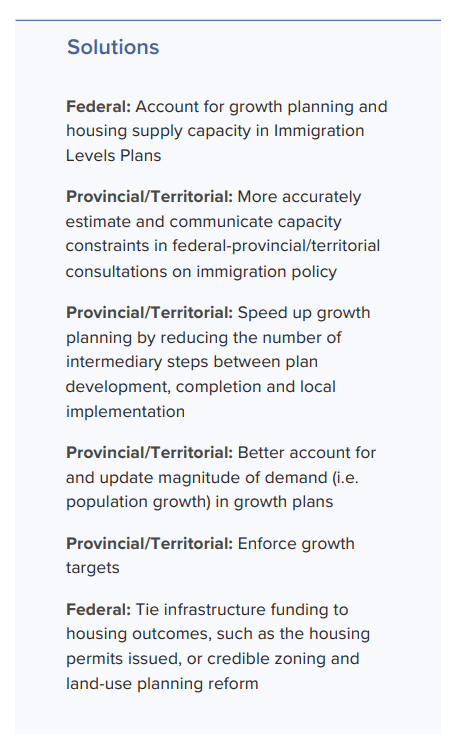

Both immigration targeting and growth planning play essential roles in determining Canada’s housing demand and supply dynamics. They are therefore equally essential to any efforts to bring these dynamics into better balance. In the same way that growing households and businesses attempt to anticipate and manage their future needs, so too must Canada and its communities prepare for change.

Both immigration targeting and growth planning play essential roles in determining Canada’s housing demand and supply dynamics. They are therefore equally essential to any efforts to bring these dynamics into better balance. In the same way that growing households and businesses attempt to anticipate and manage their future needs, so too must Canada and its communities prepare for change.

Immigration targeting does itself no favours, however, when it is determined in the absence of considerations for housing supply systems’ ability to accommodate accelerated growth. Likewise, growth planning does itself no favours when it takes too long to conduct, when it is not informed by the latest or most accurate information, and when its provisions are not enforced. Without improving upon these shortcomings, housing supply systems will, inevitably, continue to fall short of Canada’s housing needs.

Breaking this cycle of increasing demand and lagging supply will require better coordination among all levels of government. Rather than working at cross purposes, governments should better account for the contingent actions of other governments. Similarly, they should better communicate their actions with regards to both housing demand and supply.

Regarding demand, the federal government can better calibrate Immigration Levels Plans by actively inquiring into the growth plans and capacity of provinces, territories and communities. Further, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, which requires the federal government to consult with provinces and territories when determining immigration targets, could be amended to specify the need to account for capacity constraints.

Provincial and territorial governments, in turn, can better estimate such capacity constraints, for example by improving development tracking and oversight systems. These constraints could then be incorporated into the federal-provincial/territorial agreements guiding consultations on immigration policy.

Regarding supply, provincial and territorial governments could improve growth planning processes on three fronts. First, they could speed up growth planning by reducing the number of intermediary steps by which provincial/territorial growth plans or policies translate into tangible local land-use policies and bylaws. For example, zoning bylaws could be immediately updated upon changes to local official plans, or even provincial growth plans.

Second, provinces and territories could ensure growth planning – at all levels – more accurately reflects the magnitude of demand. Doing so would require close coordination with the federal government regarding evolving immigration policy, and the anticipated levels of population growth it determines. It would also require the rapid incorporation of these levels into growth plans, which would need to remain nimble in the face of change.

Third, provincial and territorial governments could more actively enforce any growth targets they set (Lafleur and Filipowicz 2023). As the order of government responsible for land-use planning and local governments, they have within their power the ability to track, incentivize, and penalize local government performance when it comes to homebuilding targets. Further, provinces and territories may, in extreme cases, give themselves the authority to directly approve housing development proposals.[7]

The federal government also has some supply-side levers that it could pull, such as tying infrastructure spending to zoning reform or supply outcomes. Large public transit projects are often funded by tri-level agreements between the federal, provincial, and municipal governments. Most of these projects are justified in part based on the idea that they will spur “transit-oriented development.” In other words, that building more public transit will lead to more development, which will increase ridership. However, that often fails to materialize in part due to zoning constraints or failure to secure development approvals. The federal government shouldn’t be willing to finance infrastructure projects that are largely premised on intensification if municipal governments are not willing to facilitate the process.

As this list of potential solutions to both demand and supply-side issues suggests, all governments have important roles to play. However, it is provinces and territories that are uniquely positioned at the nexus of both demand and supply. On the demand side, they coordinate with the federal government, which consults with them as it produces annual Immigration Levels Plans. On the supply side, provinces and territories govern land-use and growth planning, and liaise directly with municipalities, which also fall under their purview. As such, provinces are well placed to better understand and shape supply constraints and capacity, while also clearly and coherently communicating these constraints directly in the design of population growth targeting.

Conclusion

Housing affordability in Canada continues to deteriorate. This has been driven in part by a growing gap between housing construction and population growth. This gap is in part driven by a lack of inter-governmental coordination. In particular, the federal government sets immigration levels without much thought to housing policy, while municipal and provincial governments set housing policy without sufficiently accounting for population growth.

This report has proposed a number of potential policy options. In broad terms, Canada needs a better alignment of federal, provincial, and municipal policies related to housing. So long as we have policies that boost housing demand while preventing the supply of new housing from keeping up, Canada will continue to face worsening housing challenges.

About the authors

Josef Filipowicz is an independent policy specialist focusing on urban and regional policy issues, including land-use regulations, housing affordability, property taxation, and municipal finance. He previously held roles at the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and the Fraser Institute, and holds an M.A. in Political Science from Wilfrid Laurier University and a Bachelor of Urban and Regional Planning from Ryerson University. Beyond his research, Josef also comments frequently (in English and French) on policy issues in his fields, notably through radio and television interviews, panel discussions, public presentations, and blogs and op-eds. His work has been featured in numerous news outlets including the Wall Street Journal, Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, Maclean’s, Detroit News, and Financial Post.

Steve Lafleur is a public policy analyst with over a decade of experience working for Canadian think tanks. He is a former Senior Policy Analyst at the Fraser Institute. He holds an M.A. from Wilfrid Laurier University. His work has appeared in most major Canadian media outlets including the Globe and Mail, the National Post, and the Toronto Star.

References

City of Vancouver. 2022. Our Process: Creating the Vancouver Plan. City of Vancouver. Available at https://vancouverplan.ca/our-process/.

Filipowicz, Josef, Steven Globerman, and Joel Emes. 2020. Changes in the Affordability of Housing in Canadian and American Cities, 2006-2016. Fraser Institute. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/changes-in-the-affordability-of-housing-in-canadian-and-american-cities.pdf.

Filipowicz, Josef and Steve Lafleur. 2023. Canadian homebuilding has not kept pace with population growth. Fraser Institute. Available at https://www.fraserinstitute.org/blogs/canadian-homebuilding-has-not-kept-pace-with-population-growth.

Government of British Columbia. 2022. “New Premier Delivers Action to Expand Housing Supply Within First Days.” Government of British Columbia. Available at https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022PREM0065-001745.

Government of Canada. 2017. Canada-Ontario Immigration Agreement – General Provisions 2017. Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/mandate/policies-operational-instructions-agreements/agreements/federal-provincial-territorial/ontario/immigration-agreement-2017.html.

Government of Canada. 2018. Canada-Ontario-Toronto Memorandum of Understanding on Immigration. Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/mandate/policies-operational-instructions-agreements/agreements/federal-provincial-territorial/ontario/canada-ontario-toronto-immigration.html.

Government of Canada. 2022a. “CIMM — 2022-2024 Multi-Year Levels Plan – February 15 & 17, 2022.” Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/committees/cimm-feb-15-17-2022/2022-2024-multi-year-levels-plan.html.

Government of Canada. 2022b. “Federal-Provincial/Territorial Agreements.” Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/mandate/policies-operational-instructions-agreements/agreements/federal-provincial-territorial.html.

Government of Canada. 2022c. “Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2023-2025 Immigration Levels Plan.” Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/notices/supplementary-immigration-levels-2023-2025.html.

Government of Canada. 2023. “Study Permit: Get the Right Documents.” Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/study-canada/study-permit/get-documents.html.

Government of Ontario. 2020. A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Government of Ontario. Available at https://files.ontario.ca/mmah-place-to-grow-office-consolidation-en-2020-08-28.pdf.

Government of Ontario. 2022. “Premier Ford Holds a Media Availability , November 7.” Youtube. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6O7hf3YShA.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai and Enrico Moretti. 2019. “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 11 (2): 1-39.

Lafleur, Steve and Josef Filipowicz. 2023. “Ontario’s Growth Targets Won’t Solve the Province’s Housing Crisis.” Policy Options. Institute for Public Policy Research. Available at https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/march-2023/ontario-housing-crisis.

Metro Vancouver. 2022. Metro 2050: Regional Growth Strategy. Metro Vancouver. Available at http://www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional-planning/PlanningPublications/Metro2050.pdf.

Ontario Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal. 2006. Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Ontario Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal. Available at https://simcoecountygreenbelt.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Place-To-Grow-Plan-2006.pdf.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. 2023. “Housing prices (indicator). Doi: 10.1787/63008438.” OECD. Available at https://data.oecd.org/price/housing-prices.htm.

Statistics Canada. 2016. “Immigrant.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=Unit&Id=85107.

Statistics Canada. 2022a. “Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E.

Statistics Canada. 2022b. “Immigrants make up the largest share of the population in over 150 years and continue to shape who we are as Canadians.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. 2023a. “Table 17-10-0005-01 Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000501.

Statistics Canada. 2023b Table 17-10-0008-01 Estimates of the components of demographic growth, annual. < https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000801,> as of March 2, 2023.

Statistics Canada. 2023c. “Table 34-10-0126-01 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, housing starts, under construction and completions, all areas, annual.” Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3410012601.

Statistics Canada. 2023d. “Table 34-10-0127-01 Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, vacancy rates, apartment structures of six units and over, privately initiated in census metropolitan areas. Statistics Canada. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3410012701.

Urbanation. 2023. “Rentals.ca February 2023 Rent Report.” Urbanation. Available at https://rentals.ca/national-rent-report.

Zussman, Richard. 2023. “B.C. Housing Minister Calls on Ottawa to Tie Housing Funding to Immigrant Arrivals.” Global News (January 3). Available at https://globalnews.ca/news/9385437/b-c-housing-minister-calls-on-ottawa-to-tie-housing-funding-to-immigrant-arrivals/.

[1] See Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2022; 2018); Filipowicz and Lafleur (2023).

[2] Statistics Canada defines immigrants as follows: “Immigrant refers to a person who is, or who has ever been, a landed immigrant or permanent resident. Such a person has been granted the right to live in Canada permanently by immigration authorities. Immigrants who have obtained Canadian citizenship by naturalization are included in this group” (Statistics Canada 2016).

[3] Statistics Canada defines net non-permanent residents as follows: “A non-permanent resident is a person who is legally in Canada on a temporary basis under a valid document (work permit, study permit, other permit) for that person along with members of their family living with them. This group also includes individuals who seek refugee status upon or after their arrival in Canada and remain in the country pending the outcome of processes relative to their claim” (Statistics Canada 2023b).

[4] “The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act requires that a projection of permanent resident admissions for the coming year be tabled in Parliament by November 1 of the preceding year, or if the House is not in session, within 30 sitting days once the House resumes. By setting targets and planning ranges for each of the immigration categories, the Government establishes priorities among economic, social, and humanitarian objectives. Levels planning then enables the Department and its partners, including provinces and territories, to allocate processing, security, and settlement resources accordingly. The Department also has a statutory obligation to consult provinces and territories on its projections in the levels plan” (Government of Canada 2022a).

[5] For a full list of federal-provincial/territorial immigration agreements, see Government of Canada (2022b).

[6] Recent increases in rental vacancies, posted in 2020 and 2021, are the result of pandemic-era population dynamics (i.e., renters leaving Toronto and closed borders). Pre-pandemic trends resumed in 2022.

[7] There is precedent to this approach, including most recently the government of Nova Scotia’s decision to grant its municipal affairs and housing minister the authority to review and approve housing development proposals in nine “special planning areas” across the Halifax Regional Municipality.