By David Abonyi and George Abonyi, July 29, 2025

A condensed version of parts of this article was published in The Hill Times on March 26, 2025.

Trump’s disruptive tariffs are the tip of the iceberg to a broader goal: rewiring the world’s economic, political, and security architecture.

It’s part of the new global reality Canadians are facing. The United States has been the cornerstone of Canada’s external economic relations. That’s served Canada well, and will continue to do so. But the world order is shifting, shaped largely by geoeconomics – state use of economic policy to achieve geopolitical objectives. Trump’s strategy is the most extensive example. It has a particular focus on China, given its global role and extensive impact on the US.

Canada must respond with a robust economic strategy. It should include calculated economic diversification with a focus on the Indo-Pacific region.

This article, the first in a two-part series, focuses on the return of geoeconomics, and the related Trump strategy. Canada’s challenge is to develop an effective economic strategy in response. Part two will address how a focused and novel implementation of Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS) can play an important role.

Return of geoeconomics

Not long ago, the going concern was with “…how [Biden’s] Inflation Reduction Act changed Canada.” It spurred government support for Northvolt, Volkswagen, and Stellantis-LGES electric vehicle (EV) battery manufacturing, estimated at $43.6 billion. The Biden Administration also introduced the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and CHIPS and Science Act with the similar objective of fostering investment in the US, and linking economics and security.

These initiatives, and the Trump tariffs, serve the same economic purpose. Tariffs, export and import controls, and industrial strategies such as subsidies, are intended to boost domestic production at the expense of foreign manufacturing.

They signal the return of geoeconomics in reshaping the global economy. Governments are displacing firms as the main decision maker in a widening range of product markets, from medical supplies to energy, from semiconductors to agriculture. They intervene for political goals, and to seek advantages for their economies and enterprises. Geoeconomics is a fundamental shift from economic policy to an earlier tradition of economic statecraft.

As a result, the World Bank cautions that “International discord – about trade, in particular – has upended many of the policy certainties,” and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warns that “…tariffs and uncertainty will lead to significant slowdown in global growth…”.

Trade restrictions

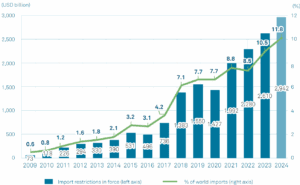

The Trump tariffs are the most dramatic example of geoeconomics reshaping global trade. But government restrictions on trade have been accelerating in recent years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Cumulative trade coverage of import-restrictive measures on goods 2009–2024

Source: World Trade Organization, WTO Trade Monitoring Report, November 20, 2024

Semiconductors (chips) – a critical input to a wide range of industries – provide a clear illustration. The 2022 US CHIPS and Science Act was followed by additional controls that involve laws and regulations restricting the export of selected goods and technology. China’s related controls on key minerals expanded its general use of export controls. The EU introduced the European Chips Act in 2023, and Brazil extended its Support Programme for the Technological Development of the Semiconductor Industry (PADIS).

Governments can also hold firms indirectly responsible for their global supplier networks through secondary tariffs, as exemplified by the expanded U.S. Foreign Direct Product Rules. For example, a Canadian manufacturer in Malaysia must now monitor its entire production system supply chain’s inputs, and equipment used for all products, to ensure that at no stage is it indirectly violating export controls.

Trade restrictions are a classic example of geoeconomics at work. They are government interventions to support domestic economic and political objectives. Tariffs have been a particularly important tool in trade policy, varying across countries, geographic regions, and sectors. Their primary roles are to protect domestic industries, both emerging and declining, as well as to safeguard technological and economic security. They are also seen as a potential source of government revenues.

For enterprises, trade restrictions can disrupt production processes, impact the availability and cost of required inputs, constrain sales in international markets, and limit access to capital and market capitalization. For the global economy, they pose significant challenges to industries and to inflation management, and can lead to economic fragmentation, instability and slower growth.

Supply chain disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic marked a sharp increase in government interventions in supply chains to ensure availability of critical medical supplies. Supply chain disruptions include trade constraints, environmental regulations, and labour laws. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the US Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act are examples.

Government interventions disrupting supply chains come in many forms. Trade restrictions on imports and exports are one set of disruptions. Subsidies to domestic enterprises are another – for example, direct grants, tax incentives, or preferential access to financing. Local content policies are yet another form, requiring enterprises to include a specified amount of locally sourced inputs in their domestic production processes, as in the case of “Make in India”.

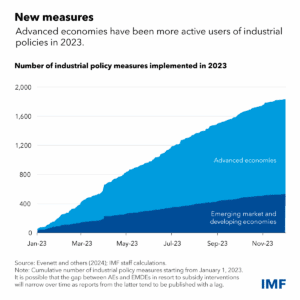

These policies signal the resurgence of industrial policy (Fig. 2) encompassing a variety of disruptive government interventions on production, investment, and trade. They are aimed at the development of specific industries and geographic areas, climate change mitigation, security, or domestic market promotion.

Fig. 2: Cumulative number of industrial policy measures implemented in 2023

Source: IIlyina Anna, Ceyla Pazarbasioglu, Michele Ruta, “Industrial Policy is Back But the Bar to Get it Right Is High,“ International Monetary Fund, August 12, 2024

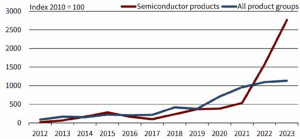

EV supply chains, a priority for many countries, are shaped more by government strategy than market or technology-driven decisions of private firms. Semiconductors again provide a vivid example. Policy interventions related to semiconductors (Fig. 3) impact key intermediate inputs such as batteries – the heart of the EV supply chain – motors, and electronic control systems. They are likely to be even more disruptive with development of connected and autonomous vehicles.

Fig. 3: Number of policies targeting semiconductors vs. all products over time

Source: Hillrichs Dorothee and Anita Wölfl, 2025

Trump strategy: geoeconomics on steroids

The inferred Trump strategy seeks to reshape the global system to align with U.S. interests. In this it rhymes with the 1971 Nixon Shock, that also used tariffs as leverage in dismantling the dollar-gold link underpinning the Bretton Woods international system.

The “reconstruction” of the Trump strategy is based on writings and presentations by Stephen Miran, chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers; Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent; and former US trade representative Robert Lighthizer. The problems the strategy aims to address, and the desired outcomes, are relatively clear. Some of the tactics are very visible, particularly the use of tariffs. Other elements, although based on the above sources, are more speculative. At this stage, the likely outcomes are also uncertain.

The Trump strategy addresses perceived problems attributed to the global role of the American dollar – in particular, persistent U.S. trade deficits since the 1970s. The U.S. dollar’s value is driven up by foreign demand for American dollar-denominated assets, given its dominant role as reserve currency and in international financial transactions.

Resulting dollar appreciation is seen as undermining industry competitiveness, leading to continuing trade deficits, loss of manufacturing jobs, and security vulnerabilities. China is of particular concern. In that context, the U.S. dollar is seen as an “exorbitant burden.” Yet it also provides “exorbitant privilege” through access to lower cost imports, cheaper finance – though this erodes fiscal discipline – and geopolitical leverage.

The Trump strategy – at times referred to as the “Mar-a-Lago Accord” – seems to aim at a relatively orderly devaluation of the dollar to reduce its domestic impact as an “exorbitant burden.” But it also seeks to maintain the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege.”

Although tariffs are the actual actions taken to date, the broader strategy appears to aim at debt restructuring. This restructuring’s means are rather uncertain. Some suggested elements involved in the strategy are persuading foreign central banks to convert higher interest shorter-term US treasuries into ultra-long-term securities and domestic currencies, and dollar-backed stablecoin initiatives. These would lower the value of the dollar but keep its global role.

The extensive tariffs are to provide negotiating leverage with foreign governments, particularly China. In return for access to the US market, Trump seeks to induce foreign firms to produce in the US, and to initiate structural reform of the world trade system. There is an understanding by key Asian economies of the central role the dollar plays in the Trump strategy, and that negotiations are quite likely to shift from tariffs to exchange rates.

The Trump strategy has important domestic components aimed at stimulating consumer spending and business investment. These include tax cuts and regulatory reforms. Tariff revenues are also expected to help reduce the fiscal deficit, making planned tax cuts more manageable.

The strategy also links economic and security concerns. Participating countries are to pay a larger share of their defense, and increase investments in the U.S., including in security-related supply chains. In return, they will remain under the U.S. security umbrella and receive tariff relief and market access.

This inferred strategy has significant uncertainties and risks. There are concerns that attempts to re-engineer the dollar’s role could lead to a loss of trust in the currency, American financial institutions, and the benchmark status of US treasuries for pricing global debt. Furthermore, private investors – who have very different incentives than central banks – now hold a greater share of US treasuries. Although the global dominance of the dollar is unlikely to change anytime soon, alternative payment systems and reserves are developing.

Tariffs can increase prices, inflation, and financial volatility, which may not be easily manageable. They may also not yield expected results in negotiations, or sufficiently expand domestic production and attract foreign investment to fill potential gaps they may cause. Export controls may not have the anticipated effects, as in the case of ethanol.

There is also domestic political uncertainty. Given the lag between policy and outcome, the Trump strategy is a race between economic adjustment and politics. Will domestic manufacturing expand substantially and quickly enough to replace imports? If the desired economic benefits are slow to emerge before the midterm and/or next presidential elections, the strategy may not be politically sustainable, particularly under a new president.

The Trump strategy’s overall outcome is uncertain. There are two possible extreme scenarios, centred on the leading protagonists, the US and China. The pessimistic scenario is where high tariffs lead to a prolonged trade war, financial sanctions, and significant tightening of global financial and liquidity conditions. The result is greater volatility, substantial uncertainty, and lower growth. This would involve a collapse of the present multilateral order, global financial and trade fragmentation, and instability. The US and China would accelerate attempts to create competing spheres of influence.

The optimistic scenario is one where aggressive tariff policy leads to wider renegotiation of key issues, and collaborative restructuring of the global system. A de facto international economic coordinating mechanism would emerge, leading to greater alignment of macroeconomic policies and exchange rates. In the shorter term there would be greater volatility, uncertainty, and lower growth as a new global order is negotiated and evolves. But over the longer term, a US–China accommodation would develop, resulting in global rebalancing, and a restructured, more stable global system.

The ongoing US–China negotiations suggest that although there is interest in realizing the optimistic scenario, the outcome is uncertain. For Canada, the implication is that a robust economic strategy is essential as a response to either extreme outcome, or anything in between.

Conclusion

The United States will always be Canada’s primary and dominant economic and security partner. However, in the face of continuing global economic uncertainty, it is important Canada diversify its economic linkages to manage risks and take advantage of emerging opportunities.

In this, the Indo-Pacific – the fastest growing region even in these turbulent times – offers significant opportunities. Part 2 addresses briefly why Canada should focus on the Indo-Pacific region, provides an overview of Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, and suggests examples of novel and focused regional initiatives that are likely to serve the interests of Canada and a changing region.

David Abonyi is director of the project “Strengthening Thai-Canada Business Linkages,” originally an initiative of the Thailand Economic Cooperation Foundation in Bangkok.

George Abonyi, resident of Ottawa, is senior research fellow and visiting professor at the Sasin School of Management of Chulalongkorn University and senior adviser to the Fiscal Policy Research Institute, affiliated with the Ministry of Finance, Royal Thai Government.