This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, October 31, 2025

In a speech last week, Prime Minister Mark Carney repeated a line he had used to great effect earlier this year: “This decades-long process of an ever-closer economic relationship with the United States is now over.”

As a consequence, he went on to say, “Our goal for Canada is to double our non-U.S. exports over the course of the next decade,” from roughly $300 billion today.

And as if to reinforce the point, President Trump (though seemingly in response to an innocuous TV ad by Ontario) ended all trade negotiations with Canada the next day and increased the tariff on some of our exports by 10 percent.

There has been no shortage of analysts unpacking whether doubling non-U.S. exports might be possible.

Unlike much of what has already been written, though, I tend to think the goal is easy.

Yes, easy. But in terms of boosting Canada’s economy, it won’t do much.

Canada’s non-U.S. goods exports

Let’s start with goods.

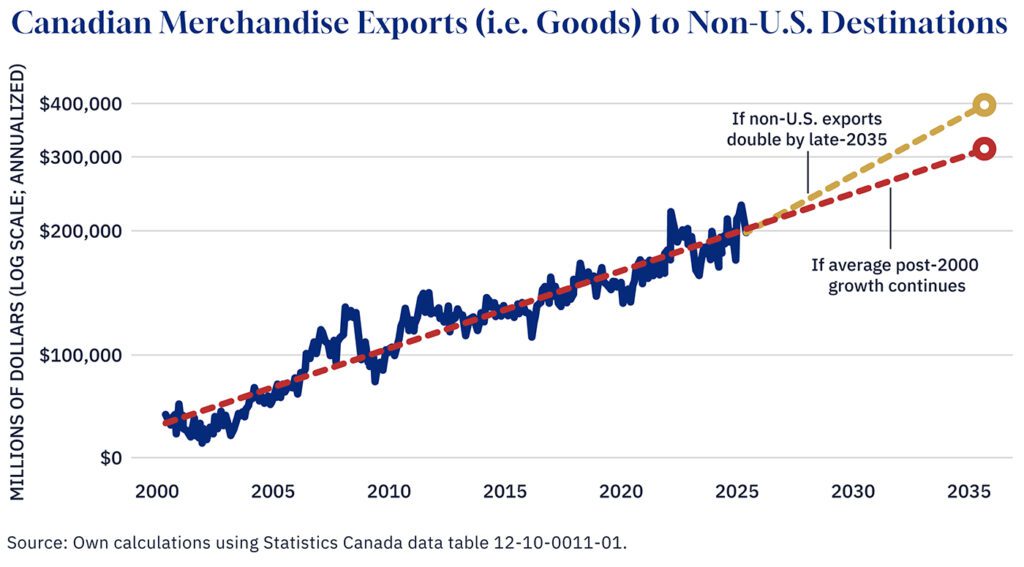

We’ve already doubled the value of such exports over the past 15 years. Doubling again over the next 10 years requires faster growth, but not insurmountable. Instead of growing at just under 5 percent annually, we’d need to push that up to just over 7 percent per year (roughly what we saw between 1998 and 2008) or we’d fall roughly $80 billion short of the target.

But if the trend observed from mid-2019 through today were to continue for the next 10 years, we would effectively be on track to nearly double total non-U.S. goods exports from that alone.

Don’t forget services!

Add in services, as the government did in previous commitments to grow non-U.S. exports, and the picture looks even brighter.

Last year, Canada exported approximately $108 billion worth of services to non-U.S. countries—roughly double the total value in 2017 and more than double the $47 billion recorded a decade earlier, in 2014.

Tourism has been on a particular tear in recent years, with sales to non-U.S. visitors (an “export” by Canada) increasing by 3.6 times over the past decade. Combined with the growth of commercial, transport, and government services, total services exports might increase by 2.6 times by 2035 if only these recent trends continue.

So, if goods exports grow at the average rate of the past decade, and services exports increase by that 2.6 times again, then by late 2035, we’d be exporting over approximately $600 billion worth of goods and services to non-U.S. markets.

That’s the goal. Done. Achieved with nothing more than continuing on with recent trends. And the economy has been anything but firing on all cylinders, making recent trends a fairly low bar.

Some policy changes still needed

Of course, facilitating that growth—especially in goods—will require improvements in physical infrastructure. We simply don’t currently have the capacity to make those shipments given our existing ports and rail systems.

The Port of Vancouver and the Port of Montreal are particularly important for enabling Canadian businesses to export overseas. Both are undergoing large expansions that were a long time coming. The Vancouver port expansion, for example, was stuck in a regulatory morass for nearly a decade before finally receiving the green light.

More can be done for other ports, too, as well as improving our rail.

The importance of energy

Then there’s Canadian energy—arguably the single best way to boost non-U.S. exports.

Consider the impact of an additional oil pipeline allowing for 1 million barrels per day to be exported overseas. That single project could generate as much as $30 billion in non-U.S. exports, given where prices are today. That’s 10 percent of the entire goal, and roughly equivalent to 15 percent of the entire value of non-U.S. exports today.

Of course, filling a new pipeline would require increased production. And that presents a major challenge, as current federal policy makes it difficult to invest in expanding Canadian energy output. Inefficient policies (such as sector-wide emissions caps or overly complex, uncertain, and unworkable regulatory review processes) would need to be addressed.

Growth in other key sectors like mining, agriculture, and manufacturing is also hindered by slow regulatory approvals.

The government itself acknowledges the challenges with current regulations. That’s why it introduced legislation through Bill C-5 to exempt selected and favoured projects from those very burdens. That may very well make sense as a short-term measure—but broader reforms for the entire economy will soon be needed.

Boosting lagging productivity growth

The U.S. will always be our most important market. Growing uncertainty there makes it all the more pressing for us to improve competitiveness despite it all.

But as is now widely recognized, a significant productivity gap has emerged between Canada and other advanced economies over the past decade. Had our productivity growth simply kept pace, the economy today would be approximately 12 percent larger. That’s a far larger boost than what increased non-U.S. trade could deliver.

Long story short: doubling non-U.S. exports over the coming decade is easier than you might think. But truly boosting our economic strength requires the federal government to change course on many fronts.

Trevor Tombe is a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, the Director of Fiscal and Economic Policy at The School of Public Policy, a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and a Fellow at the Public Policy Forum.