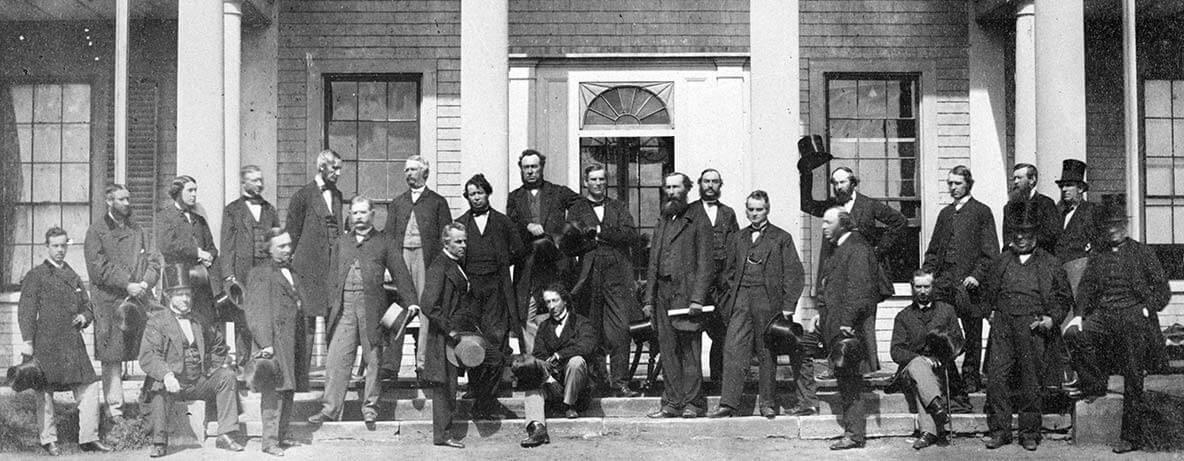

Munk Senior Fellow Alastair Gillespie, who leads the MLI Confederation Project, explores how leading statesmen from 1865 articulate the political challenges they grappled with. Here he looks at George-Étienne Cartier and A.T. Galt.

By Alastair C. F. Gillespie, February 5, 2015

George-Étienne Cartier and A.T. Galt today addressed a packed house of assembly, entering the second day of debate in the Great Coalition’s bid to unite the colonies of British North America. The meaning of this symbolic pairing was plain to all. If the new confederation is to be a success, Lower Canada’s chief ministers must allay the reciprocal fears of the French and English communities. Either minister might be driven from office, accused of having sold his country. But if trust overcomes doubt, Cartier and Galt will carry Lower Canada into confederation, and secure self-government for their new province carved out from the old Canadian Union.

Cartier led off, explaining his long rearguard battle against representation by population, now the basis of representation in the new parliament. He was “accused of being opposed to Upper Canada’s rights,” but with two provinces governed by one legislature, “constant political warfare” would result. He had never opposed “rep by pop” from any unwillingness to do justice to Upper Canada. However “when justice was done to Upper Canada, it was his duty to see that no injustice was done to Lower Canada.”

Federation changed the position entirely, said Cartier, as he first realized in 1858 when the Cartier-Macdonald ministry adopted it as policy. With other colonies as counterweights to powerful Upper Canada, there was a balance of power in favour of federation: “if three parties were concerned, the stronger would not have the same advantage … when it was seen by the third that there was too much strength on one side, the third would club with the weaker combatant to resist the big fighter.” Even outnumbered in the federal parliament, French Canadians had nothing to fear: “Any attempt to deprive the minority of their rights would be at once thwarted. Under the Federation system, granting to the control of the General Government those large questions of general interest in which the differences of race and religion had no place, it would not be pretended that the rights of either race or religion could be invaded at all.”

Galt, as Finance Minister, shifted ground to our new country’s trade, resources and material prospects, matters he said which “bear no reference to what may be the creed, nationality or language of portions of the people.” Union would break down trade barriers, protect against disruptions to United States trade, and secure the resources to develop the great North-West. Our railways and canals formed “parts of one great whole,” evidencing our “natural union.” Through them and the mighty St. Lawrence, Galt said, “a great trade will flow in one uninterrupted stream, enriching in its course not only the cities of Canada, but also swelling the tide of a new commerce we may hope to see called into being in the open Atlantic ports of St. John and Halifax.”

Though sticking to financial matters today, Galt has also reached across divides. He is a determined advocate of minority education rights, and has seen to it the new local legislatures may not touch the denominational schools of either the Protestant or Catholic minority in both Canadas. Galt speaks not only as chief of Lower Canada’s Protestant community, but something more. As a delegate to Quebec, Galt said in his recent speech at Sherbrooke he “equally represented his French Canadian friends, and his conviction was that, instead of there being any clashing and division of interests, they would be found in the future more closely bound together than ever before … to benefit Lower Canada, not French Lower Canada, or British Lower Canada — but the whole of Lower Canada.” Mr. Galt believes the French and English communities in his province can club together for protection in the new federation, as they did resisting “rep by pop” while the old Union lasted.

Cartier distilled these political facts and drew the moral of these great events. “When we were united together … we would form a political nationality with which neither the national origin, nor the religion of any individual, would interfere.” Diversity, not uniformity, was “the order of the physical world and the moral world, as well as in the political world,” it was “futile in the extreme” to imagine it otherwise. “We could not do away with the distinctions of race. We could not legislate for the disappearance of the French Canadians from American soil.” In Canada, “we should have Catholic and Protestant, English, French, Irish and Scotch, and each by his efforts and his success would increase the prosperity and glory of the new Confederacy … we were of different races, not for the purpose of warring against each other, but in order to compete and emulate for the general welfare.”

If Canada has not one language or one religion, today we were asked to be more. Galt promised continental expansion, and wealth is one sinew to bond. Some may chase glistering riches, but to unite we have now also the Cartier ideal. Some call the new nation impossible, and therein lies our great hope. Our politics disciplines our politicians, it will temper them from extremes. In a varied country with a free Parliament, only justice can appeal to all. The work will not complete in our lifetime, for strong is the call of the blood. In Canada it is better to build bridges, though we are vulnerable to those wedging divides. If we answer the call made today in the House, we may yet go forward together. Not to wage endless wars of the spirit, but by “slow prudence make mild a rugged people.”

Alastair C.F. Gillespie, a Canadian lawyer living in London, U.K., is a Macdonald-Laurier Institute Munk Senior Fellow and leader of the MLI Confederation Project.