By Lee Carson and Patrick Duxbury, October 24, 2024

NATO alliance members, including Canada, have pledged to boost their domestic defence materiel sectors. These commitments add to the mounting pressure on Canada to both achieve a 2 per cent of GDP defence spending goal and expedite its commitments to NORAD’s modernization. However, media reports claim that the Canadian government is struggling to understand the ramifications and the burden it places on the defence sector.

A national security strategy focused on the Arctic

The business of defence is evolving rapidly thanks to the accelerated growth of technology and its amazingly fast adoption in the ongoing war in Ukraine. Despite the Canadian Armed Force’s best efforts and intent (such as announcing a new cyber command), Canada’s goal of fielding a multipurpose, combat-capable force that can “manage a full spectrum of conflict” and make a “genuine contribution to security” appears unachievable. As Macdonald-Laurier Institute Senior Fellow and defence expert Richard Shimooka recently wrote, “there are simply too few dollars chasing too many priorities.”

Therefore, and as International Relations professor Andrew Latham recommends, Canada must prioritize – specifically, with a focus on the Arctic. Here are the reasons why:

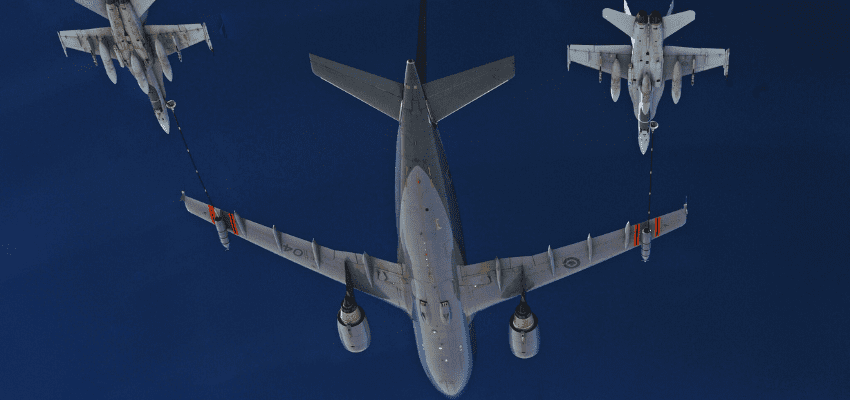

1. Canada has a NORAD treaty commitment with the United States to share in the defence of North America – primarily against threats emanating from Russia, and increasingly China, that cross over the Arctic. Under pressure, the federal government committed to a major investment in NORAD modernization in July of 2022. While this was a good start, Ottawa is struggling to meet that commitment in a timely manner. Meanwhile the United States, mindful of the growing tensions and military threats in the Arctic, has just published its own National Strategy for the Arctic Region that lays out the Arctic capabilities it needs, while also stressing the need to rely more on Arctic allies in order to reduce pressure on a thinly stretched US military.

2. NATO recently expanded with the addition of two Nordic nations: Sweden and Finland. While NATO has not historically placed much priority on the Arctic, that has now changed. Canada now represents the northwestern flank of NATO, and the whole alliance is looking to us to defend that key territory while also contributing to the defence of the European side.

3. We have a perennial need to protect our own Arctic territory, which means defending and securing the region, and not just as an approach to the rest of North America and/or NATO. This includes the waters (surface and subsurface) of our Arctic Archipelago, which Canada asserts as internal waters, but that the US considers an international strait.

4. Finally, we are trending that way already, thanks to our most recent defence policy update, “Our North Strong and Free,” which nudges the CAF towards Arctic prioritization if not specialization.

If Canada materially focuses on the Arctic, it will be very constrained to perform missions elsewhere (it can scarcely do that now at any rate). However, by focusing on the Arctic homeland, and by building on its domestic Arctic capabilities, Canada will be positioned to perform its most important mission effectively.

An Arctic, and Arctic-led, defence industrial policy

Around 2018, Canada developed an Industrial Technological Benefits (ITB) strategy that sought to leverage defence spending through innovations and exports related to our “key industrial capabilities,” or KICs. The results have been modest, to be charitable. The federal government chose KICs in niche areas that it believed Canadian industry was a leader. However, in many cases, they seemed like the promoted brands of the last lobbyists in the door.

The policy has other problems. Rather than facilitate the procurement of proven and world-leading KIC technology-based products from Canadian suppliers, it encourages our businesses to re-invent those products through research and development in partnership with academia. This has the effect of encouraging a risk-adverse defence department to procure equivalent off-the-shelf products from offshore suppliers.

An Arctic specialization would provide the opportunity for Canada to reset and refocus our defence industrial policy. We need to develop key domestic industrial capabilities that allow the CAF to work in and defend the Arctic – including in the areas of Arctic mobility, sensing, and communication. We also need to address the Arctic infrastructure deficit. Anita Anand, the former defence minister, said it clearly when she announced NORAD modernization in 2022, calling for “next-generation defence technology, infrastructure development, logistics, base operations, and in-service support.” While next-generation defence technologies are not necessarily Arctic specific, the other four certainly are essential capabilities particular to the Canadian Arctic.

There is a potential flaw to this logic: while Canada is indisputably an Arctic country, relatively few Canadians have visited Canada’s North, let alone lived and worked there. As Canada’s defence policy inexorably moves north, we must address the human side of these Arctic KICs. It is our view that the development of Arctic defence capabilities must be led, or at least done in partnership with those people that call the North home; that especially includes the Inuit of Canada and the businesses that they own and operate. Thankfully, the modern nation-to-nation governance framework that is in place to guide Canada’s constitutional relationship with the Inuit provides a strong foundation for partnership.

Modern treaties are in place across the Inuit Homeland (Inuit Nunangat) and helping to uphold these treaties is Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK), the national representational organization that aims to protect and advance the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada. In the Arctic regions that ITK represents, there exists Regional Development Corporations. These “DevCorps” primarily act as holding companies and are directed by their Inuit government-shareholders to own and manage profitable ventures, while also pursuing social outcomes that help improve the quality of life of Inuit in the regions that they represent. Collectively across Inuit Nunangat these Inuit DevCorps own and operate more than 100 companies. Many have developed impressive capabilities that are or will be needed for Arctic defence, including infrastructure development, logistics, in-service support, and base operations. Further, they are not all small companies. They include Nasittuq Corporation, the prime contractor for DND’s largest currently running Arctic in-service support contract. It includes Canadian North, northern Canada’s main airline. They also include a suite of mining service and construction companies that for decades have managed to build and operate in some of the most remote and challenging locations on the planet.

Complementing those Inuit companies are southern Canadian companies with their own rich Arctic credentials. These include Davie Shipbuilding, now a world leader in icebreaker production, C-Core and its global leadership in ice and ocean engineering, Telesat with its Lightspeed satellite communications constellation, and ATCO Frontec with its decades of experience in serving defence and security operations across the Arctic, to name but a few.

Putting it all into place

The global security issues happening around us won’t wait for Canada. The incoming Canadian Chief of Defence Staff is on record saying we have five years to prepare to counter long range threats coming through the Arctic. Meanwhile the US is moving forward rapidly on NORAD modernization, with or without us. The good news is that governance structures, precedents, and policy tools are already in place and available to be applied.

First, the defence department’s Arctic specialization should focus on NORAD modernization, including ancillary procurements concerning fighter jets and patrol submarines. These complex procurements must be run as an integrated program, as opposed to a portfolio of interdependent projects. As explained by KPMG defence sector experts Grant MacDonald and Dan Doran, this requires an integrated program office that includes leaders from all stakeholder groups, including government departments and industry partners. For the NORAD modernization projects in the North, industry partners by necessity must include the Inuit Development Corporations that are already engaged in building, operating, and maintaining assets from the Alaska border to the Labrador coast. Canada must draw on the experience of these companies if it has any hope of expediting its NORAD modernization ambitions in the North.

The precedent for such a partnership program is the National Shipbuilding Strategy (NSS). This program, still touted by the government as a success story, is helping restore Canada’s shipyards, rebuild our marine industry, and create sustainable jobs in Canada while ensuring our sovereignty and maintaining our interests at home and abroad. In essence, it works as a strategic partnership between the Government of Canada and selected shipyard prime contractors to streamline procurement. The NSS is not perfect – it offers many invaluable lessons for the federal government, but they must be applied to its NORAD modernization partnerships with Inuit businesses.

In addition, Ottawa needs to innovate its governance approach to this nation-building endeavour. Projects of the anticipated scale and complexity require both a whole-of-government approach and a deep bilateral partnership between Canada and Inuit. Thankfully, that partnership vehicle already exists! The Inuit Crown Partnership Committee (ICPC) is co-chaired by the prime minister of Canada and the president of the ITK, and is supported by all key federal government departments and regional Inuit leadership. Its purpose is to advance shared priorities and create a more prosperous Inuit homeland. Ideally, the departments responsible for NORAD modernization projects in the North should report up to the ICPC and be prepared to act upon the advice provided by the federal ministers and Inuit leaders who make up the committee. Such an approach would be a game-changer.

Nation building is nation defending

Canada must defend its own national security and sovereignty issues and should restore its standing as a valuable and respected contributor to our security alliances. With a focus on the Arctic and wise policy decisions we can do so while responsibly working in a true partnership with our own Inuit businesses and communities. This is an opportunity we cannot miss.

Lee Carson is the president of NORSTRAT Consulting Inc.

Patrick Duxbury is the executive director of the Inuit Development Corporation Association.