This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Richard Shimooka, January 6, 2023

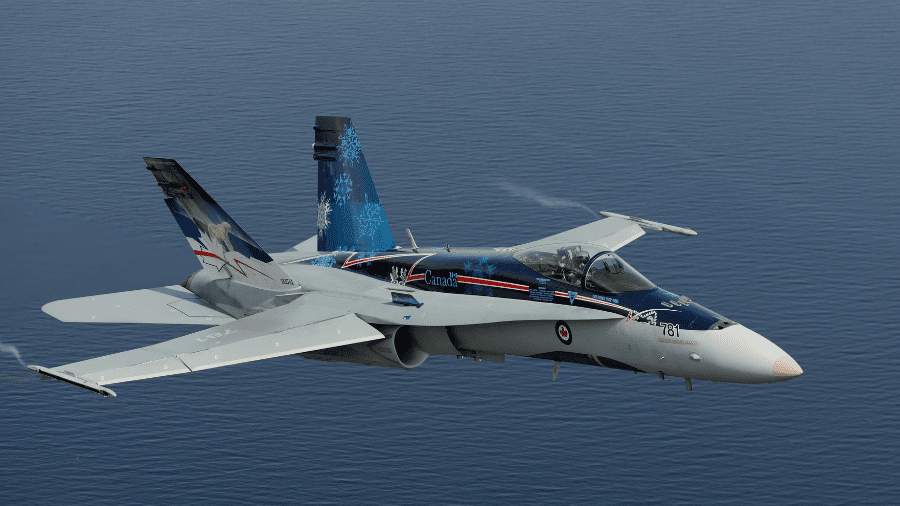

In the days leading up to Christmas, the government quietly made the decision to acquire the F-35. This should be the final step in the long-running saga to replace the CF-18, and the timing was fairly revealing—it is a file that this government wants to draw as little attention to as possible, given how poorly it has handled it.

Many Canadians may be confused by this development, as the government had seemingly stated last March that the F-35 would be Canada’s next fighter. Yet what was announced at the time was that it was the preferred solution, and the government would now enter into negotiations with Lockheed Martin and the U.S. government to finalize the contract. While there was the possibility that Ottawa might have decided to go to the second-place bidder, such an outcome has never occurred with a major Canadian procurement program.

On the surface, this may seem like an orderly process, but the reality is that it reflects a serious governance failure around the procurement. Yet this was an obfuscation; in reality, this was a needlessly drawn-out process that further increased the cost to Canadians and detrimentally affected the country’s security.

In 2014, the Harper government decided for the second time to acquire the F-35. Their negotiation for it—which was also more complex than the 2022 procurement because it incorporated a swap with the U.S. government to deliver four aircraft within a year in order to accelerate the transition—required four months. This should be seen as a baseline for comparison to the current situation, where the Trudeau government has taken 10 months to make a similar decision.

Much of the delay arises from allowing bureaucratic parties to hold up progress because of resistance to the method by which the F-35 had to be procured. While the typical refrain for this sort of objection is that these parties are ensuring the “integrity” of the process and obtaining the best value for money, it does nothing of the sort.

In reality, the government had no real ability to alter any part of the contract under negotiation with Lockheed Martin. The government will acquire the F-35 through a unique arrangement with the U.S. government and six other countries, known as the Joint Strike Fighter Partnership. This allowed it to purchase it at the exact same cost as what the U.S. government pays. In contrast, Canada typically pays a 3-20 percent surcharge on any item purchased from the United States. The partnership also allowed Canadian firms to bid on lucrative subcontracts for all F-35s produced, which has netted $2.8 Billion dollars thus far over the past 15 years. However, to be a member, Canada was required to invest nearly $700m in membership fees and purchase F-35s for the Royal Canadian Air Force.

By acquiring F-35s through the partnership, Canada’s ability to change the contractual terms of the agreement was non-existent—those were largely established in a memorandum of understanding signed in 2006. Roughly speaking, all Canada can request is how many aircraft it wants and its preferred delivery schedule. The cost is set by the negotiations between the Joint Strike Fighter Program Office (representing the partnership) and Lockheed Martin. The program office then merely attempts to align this request with available slots in the production line. This is why Canada is only moving to acquire 18 aircraft out of a total fleet of 88 at this time—Ottawa must wait for the Program Office’s negotiation on cost to occur for future years before it can select aircraft.

However, by delaying its own selection process, Canada’s delivery schedule has likely slipped. Earlier in December, Germany finalized its order of 35 F-35s, which will push the RCAF’s delivery slots further down the list. This is highly problematic considering the atrocious state of the CF-18 fleet, which requires urgent replacement. While the plan was to retire these aircraft by 2032, it’s unlikely now that this schedule will be met—which means the RCAF will have to soldier on with the aircraft that will be over 50 years old by the time they will be retired from service.

But even now the limitations of the CF-18 fleet are evident. Last week, it was announced that the RCAF will not provide a rotation of fighters to defend European skies next year for the first time in five years, in spite of the ongoing war in Ukraine and Russian threats against NATO. The reality is that the RCAF is unlikely to be able to do much more than defend North America for the next decade. In the coming years, Canada will divest half of its CF-18 fleet, leaving less than 40 aging fighters to defend Canada’s airspace and its interests. Despite being updated with new radars and weapons, the remaining aircraft will be far behind the average of all of our allies. This is a key factor behind the RCAF’s poor retention rate: personnel are aware of the fighter force’s perilous state due to years of neglect and inaction and have given up and left the service.

Simply put, this entire situation can be attributed to the Trudeau government’s lack of leadership. Even ignoring all of the missteps on this file between 2015 to early 2022, it failed to cut through irrelevant bureaucratic objections that in real terms delayed the retirement of the CF-18s by another year, and likely cost Canadian taxpayers tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars due to the cost of keeping the antiquated aircraft flying for that additional time.

While the fighter replacement saga is drawing to a close, similar dynamics are evident in other programs. Canada desperately requires a new Maritime Patrol aircraft to undertake security over our coasts. The current aircraft, the CP-140 Aurora, is now over 40 years old and has seen heavy service over the past two decades. As David Pugliese recently reported, Boeing Aerospace offered an untendered proposal to the Canadian government to replace them with eight to twelve P-8 Poseidon aircraft.

Boeing’s push is partly due to the reality that the production line for the aircraft is set to shut down in 2025, and the U.S. acquisition system requires two years lead time for aircraft to be delivered. The P-8 has become the replacement for almost every single close ally that used the same airframe as the CP-140 (known as the P-3 Orion). Countries like the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, Norway, and South Korea began an orderly replacement process that started a decade ago and is now nearing completion.

Considering the Trudeau government’s inability to deliver decisions in a timely fashion, it is quite possible that it will make a decision outside of Boeing’s window of opportunity. If Canada fails to acquire the P-8, its potential options are limited. One option, which many military officials seem to fear, is that the air force will be forced to acquire a much smaller, shorter-ranged, and less capable aircraft, perhaps based on a Bombardier 6000 series. Such an aircraft would not meet Canada’s military requirements and would likely cost more than the P-8 option due to the cost of modifying the platform to meet the RCAF’s needs.

What the entire fighter saga debacle has shown is that this government must become much more adept at making decisions in a timely fashion. Unnecessary bureaucratic processes and delays do not improve outcomes for Canada. Instead, they increase costs and compromise the country’s security. If this government is serious about improving the country’s security, this is a good place to start.

Richard Shimooka is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute, where he specializes in strategic studies, comparative defence management approaches and foreign policy.