In the Feb. 2015 edition of Inside Policy, the magazine of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute,  author Bob Plamondon details the values, principles, unique skills and circumstances that combined to make Sir John A. Macdonald so instrumental to securing agreement on Confederation.

author Bob Plamondon details the values, principles, unique skills and circumstances that combined to make Sir John A. Macdonald so instrumental to securing agreement on Confederation.

By Bob Plamondon, Feb. 10, 2015

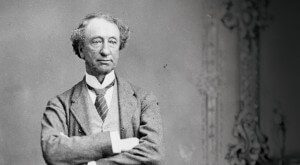

John A. Macdonald has no equal.

Born to Hugh and Helen Macdonald in Glasgow, Scotland, on either January 10 or 11, 1815, John was five years old when his family emigrated to Canada. His father was a shopkeeper, and later ran a milling business.

Family finances precluded John attending university so he entered the workforce at age fifteen at a prestigious commercial law practice. By the time he turned 20 he had his own law office in Kingston, specializing initially in criminal law before switching to a more lucrative commercial practice.

Macdonald entered the workforce at a time of political tension and uncertainty. Fuelled by a weak economy and a desire for democratic reform, matters flared up on December 6, 1837 when a group of Reform radicals led by William Lyon Mackenzie gathered with 1,000 men at the Montgomery Inn in Toronto in an attempt to seize control of the government. But Macdonald was not a reformer and was committed to British institutions, in part due to his fear that Canada would not survive annexation to the United States without the might of the British military by its side.

When running as a candidate in the 1844 election for the Assembly of the Province of Canada, Macdonald outlined the cornerstone of a vision that would endure throughout his political career: “I…scarcely need state my belief that the prosperity of Canada depends upon its permanent connection with the Mother country and that I shall resist to the utmost any attempt which may tend to weaken that union.”

Macdonald was a man of vision and progress, not details and ideology. A moderate, he was more interested in accomplishment than in debate. He had a common touch, remembered names and faces, made people laugh and feel good about themselves, and developed the reputation for being something of a charmer.

In Parliament, Macdonald fought extreme elements from both sides of the aisle. Opposing annexation by the United States, or countering Tory elements that sought to assimilate the French, Macdonald stood for tradition.

In 1847, Macdonald accepted the invitation to serve in Cabinet as Receiver General. Given Macdonald’s general disregard for his personal finances, the appointment was panned by the press. The Montréal Gazette claimed, “The intrusion of a young lawyer into the situation of Receiver General appears to our eyes, and if we are not very much mistaken, will appear also to those of the public, a blunder of the most stupid kind.”

In 1847, Macdonald accepted the invitation to serve in Cabinet as Receiver General. Given Macdonald’s general disregard for his personal finances, the appointment was panned by the press. The Montréal Gazette claimed, “The intrusion of a young lawyer into the situation of Receiver General appears to our eyes, and if we are not very much mistaken, will appear also to those of the public, a blunder of the most stupid kind.”

By the age of thirty-seven, Macdonald’s legal career was a distraction to the promising political future which beckoned. Macdonald was leadership material, not because he had great oratorical skills or passion, but because of his inclusive and amicable approach to issues and people on all sides of the legislature. A conversationalist with an endearing capacity for flattery, he was an entertaining storyteller who often used wit to extract himself from a tough spot. To one supporter’s demand for a specific patronage appointment, Macdonald countered, “Why on earth would a man like you want a paltry job like that? It’s not good enough for you. Just you wait awhile, and we’ll find you something much better.” Another man pursued Macdonald at the funeral for a deceased senator, declaring, “Sir John, I would like to take that man’s place.” Macdonald replied, “I’m afraid it’s too late. The coffin is nailed shut.”

Macdonald saw his role as a centrist coalition builder. A leading political commentator of the day described Macdonald’s unique skill: he could herd cats. Macdonald himself often used the term “catching loose fish,” by which he meant bringing to his side members with no commitment to any particular party.

Tolerant, and opposed to the rigid separation of church and state, Macdonald believed that government must recognize and respect religious diversity and the cultural divisions between English and French-speaking Canada.

In 1853, Canada East and Canada West had an equal number of seats in Parliament. When the British Parliament passed the Act enabling the Union in 1840, the population of Canada East was larger, but the 1851 census revealed that Canada West now had the greater number. Macdonald hoped to fashion a new coalition of Conservatives, combining moderate Reform elements with French-Canadian support. George Brown sought a Conservative coalition of his own that, in part, stood for the end of French-Canadian supremacy in the legislature. Macdonald was clear that his goal was to unite all the peoples of Canada, regardless of language or religion.

When George Brown attacked the notion of religious schools, Macdonald defended the historical rights of French-Canadian Roman Catholics. When the Separate School Bill passed in 1855, George Brown called it French-Canadian tyranny, and reaffirmed his commitment to representation by population. His goal was to diminish the influence of French-speaking legislators. However, it was not just the church and the language that Brown sought to control. He also wanted to make French culture extinct, just as Lord Durham had proposed in his 1839 Report on the Affairs of British North America, in which he described “two nations warring at the bosom of a single state…a struggle not of principles, but of races.”

Writing to a reporter for the Montréal Gazette, Macdonald lambasted the Anglophone attitude towards the French in Lower Canada: “The truth is that you British Lower Canadians never can forget that you were once supreme — that Jean Baptiste was your hewer of wood and drawer of water. You struggle, like the Protestant Irish in Ireland, like the Norman Invaders in England, not for equality, but ascendancy — the difference between you and those interesting and amiable people being that you have not the honesty to admit it.”

Macdonald believed that any attempt to assimilate or dominate the French was pointless and ignored reality: “No man in his senses can suppose that this country can, for a century to come, be governed by a totally un-frenchified government. If a Lower Canadian Britisher desires to conquer he must ‘stoop to conquer.’”

Macdonald’s moderate and respectful views enabled him to build bridges with French Canadians. He understood that for the French these battles were a matter of survival. Far ahead of his time, he was perhaps the first English politician to recognize the French people of Québec as a nation: “(We) must make friends with the French, without sacrificing the status of his race or religion or language (we) must respect their nationality. Treat them as a nation and they will act as a free people generally do — generously. Call them a faction and they become factious.”

Presciently, Macdonald foretold how French Canadians would react when threatened: “Supposing the numerical preponderance of British in Canada becomes much greater than it is, I think the French would give more trouble than they are said now to do. At present they divide as we do, they are split up into several sections, and they are governed by more or less defined principles of action. As they become smaller and feebler, so they will be more united; from a sense of self-preservation, they will act as one man and hold the balance of power… So long as the French have twenty votes they will be a power, and must be conciliated. I doubt very much however if the French will lose their numerical majority in Lower Canada in a hurry…I am inclined to think they will hold their own for many a day yet.”

These views were instinctive to Macdonald. His impulse was to look to the French to build a stronger coalition in the Union. On a practical level he understood that whoever could forge and sustain a partnership with francophones would govern; and that the “representation by population” forces were motivated, not by pure democratic principles, but by a desire to diminish the French fact and French influence. By standing up to these forces, Macdonald solidified his coalition with the Bleue Canadien members. “Do not put yourself in opposition to the French,” Macdonald told a colleague. “The French are your sheet anchor.”

To Brown and his ilk, Macdonald had sold his soul for the sake of power. Macdonald countered that his interest was not power, but simple fairness. His responsibility was to govern “for the good of the whole country and the equal interests of all.”

When Alexander Tilloch Galt boldly proposed the idea of establishing a federation of British North American colonies to form one great nation Macdonald was interested, but cautious.

A delegation not including Macdonald – consisting of Georges-Étienne Cartier, John Ross, and Alexander Galt – travelled to England to explore the case for a Canadian federation. The five colonies included in Canada’s proposal were Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Canada. At the time, the Maritime provinces were considering a union among themselves and were opposed to joining with the Canadian provinces. The colonial office supported Confederation but it was looking for some indication that the venture would succeed before endorsing it.

George Brown continued to articulate an alternate vision. He preferred the design of the United States of America: representation by population, a written constitution, the separation of executive from the legislature, and restraints on federal powers.

If the American model had any credibility, it vanished on April 12, 1861 when cannons were fired at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, starting the Civil War. The American design, with its weak central government, now looked flawed. With talk of a federal union of British colonies in North America, Macdonald feared that powerful provinces in a federated state of British colonies could also lead to conflict and war.

Unlike Brown, Macdonald wanted the federal government to have all the key powers of sovereignty, with one clear voice, “an immense Confederation of free men, the greatest confederacy of civilized and intelligent men that ever had an existence on the face of the globe.”

In the election campaign of 1861, Macdonald argued for his design of Confederation. He used the American Civil War not only to argue for a strong central government but to make the case that Confederation itself would counter an American takeover. The American threat was evident from many sources, including William Seward, Abraham Lincoln’s Secretary of State, who said Canada was “ripe fruit” that would naturally fall into the hands of post-Civil War America.

Not long before the critical debates on Confederation were held, the Macdonald-Cartier government resigned after a group of French-Canadian supporters sided with the opposition to defeat a bill to appropriate $500,000 for the militia in May 1862. The bill called for a military of 50,000 men, in large measure to protect Canada against an invasion from America (then in the middle of a civil war). The defeat met with annoyance in Great Britain as an editorial in the London Spectator noted in July 1862: “It is, perhaps, our duty to defend the empire at all hazards; it is not part of it to defend men who will not defend themselves.”

Yet even in defeat, Macdonald was strategic and patient. To Macdonald, there was a time to be in power and a time to consolidate a coalition, a political astuteness that led to his nickname of “Old Tomorrow.” “We can put a Ministry out whenever we like, but the pear is not yet ripe. We have shown that we did not wish to cling to office for its own sake and we wish to show that we prefer the good of the country to mere party triumph…”

When the Liberal government of John Sandfield Macdonald was defeated, John A. Macdonald and Étienne-Paschal Taché formed an administration under the banner of the Liberal-Conservative party on May 30, 1864.

The Macdonald-Taché government did not initially take the lead on Confederation. It was Macdonald’s longtime nemesis, George Brown, who introduced a resolution in the legislature asking that a committee examine alternative forms of federation. Most likely because it was a Brown initiative, Macdonald, Cartier, and Galt voted against the resolution. Nonetheless, it passed.

The committee reported on June 14 that, “A strong feeling was found to exist among members of the committee in favour of changes in the direction of a federative system, applied either to Canada alone or to the whole British North American provinces.” To Brown, a federation was akin to a divorce of Canada West and Canada East, a means to achieve both representation by population and a diminished influence by the French over Canada West. Including the Atlantic provinces in a federation was a possibility, but Brown would have been satisfied with a “mini-confederation” of Canada West and Canada East with some undefined political structure above them both. The fate of the English in Canada East was of no concern to him.

Macdonald disagreed with Brown’s intent to isolate the French, but he agreed with the design. For Macdonald, keeping the British colonies strong both affirmed Canada’s independence from America and assured its connection with Great Britain. As a result, his government was fully committed to a general federal union of British North America when, on August 29, 1864, he and some colleagues set sail aboard the Queen Victoria for Charlottetown, PEI, to drop in on a conference that was considering a possible union of the Maritime provinces.

Unlike Brown, Macdonald was determined that the Atlantic provinces would join in Confederation. Together with Galt and Cartier, Macdonald persuaded the Maritimes to set aside the idea of a Maritime-only union, not a difficult sell because the federated model would enable each Maritime province to retain its border (whereas the proposed Maritime union would have created a single entity). A second conference to consider the larger national union was scheduled for October at Québec City.

The seventy-two resolutions passed at Québec City became the basis for the British North America Act. Canada would be a federal union, formed under its “mother country” Great Britain. There would be a general government charged with matters of common interest to the whole country and local governments charged with the control of local matters in their respective sections. (It is noteworthy that the term “general” was used rather than “federal”; “local” rather than “provincial.”)

The Maritime provinces, fearful that their interests would be subservient to the larger populations of Canada East and Canada West, wanted equal representation in the Senate. However, the Senate was designed with regional, not provincial, equality in mind. There were to be 24 members each for Canada East and Canada West; and 24 for the Maritime provinces (Nova Scotia: 10, New Brunswick: 10, and Prince Edward Island: 4). In an early design members of the Senate would be appointed by the Crown, after being nominated by local governments. Those nominated were to include those from opposition parties in each province so that all political parties would be fairly represented.

Macdonald believed an appointed Senate composed of men of substance was necessary, humorously adding, “The rights of the minority must be protected, and the rich are always fewer in number than the poor.”

The general Parliament, which required elections at least every five years, had the power to make laws for peace, welfare, and good government in a broad range of categories. The local legislatures had more limited responsibilities. To ensure the authority of the general government, its laws were to be supreme in any area of shared jurisdiction. The weighting of powers and jurisdiction was, as Macdonald had sought in the negotiations, precisely toward a strong federal Parliament. “We…make the Confederation one people in one government, instead of five peoples and five governments, one united province, with the local governments and legislatures subordinate to the general government and legislature.”

Both English and French were to be used in the general Parliament and in the local legislature of Canada East, and also in the federal Courts and the courts of Canada East.

Whenever confederation was in political danger, Macdonald would raise the spectre of problems south of the border. Meanwhile, all was not well in the Maritime provinces. Prince Edward Island did not make it into the first phase of Confederation. In Nova Scotia, Joseph Howe took up the struggle against the Québec plan and demanded a referendum or election on the issue. He believed that Confederation would weaken the bond with the British; that it would be used by the British to justify withdrawing its troops from Nova Scotia, and thus weaken commercial ties.

In New Brunswick, both the Québec resolutions and Premier Samuel Leonard Tilley were defeated in the legislature. With an anti-confederation government in place in New Brunswick, expanding the union seemed doubtful. But, supported with ample secret donations arranged by Macdonald and railway supporters, Tilley was returned to power in short order and the Confederation resolution was adopted in 1866.

The Nova Scotia legislature approved the union in 1866, but its approval expired in the spring of 1867. Unless Confederation was a reality by that date, a new bill would have to be introduced. A provincial election was likely before then, providing another opportunity to derail Confederation in Nova Scotia.

Within Canada West and Canada East, the Confederation debate drew generally positive conclusions, but for different reasons. In Canada East, George Brown triumphantly declared, “…constitution adopted – a most credible document – a complete reform of all the abuses and injustices we have complained of. Is it not wonderful? French-Canadianism is entirely extinguished.”

Brown’s newspaper, the Globe, elaborated: “We desire local self-government in order that the separate nationalities of which the population is composed may not quarrel. We desire at the same time a strong central authority. Is there anything incompatible in these two things?”

In Canada East, Quebecers viewed Confederation as a framework that would allow them to control their own destiny. Editors at La Minerve, a newspaper closely aligned with the Tories, proclaimed, “As a distinct and separate nationality, we form a state within a state. We enjoy the full exercise of our rights, and the formal recognition of our national independence… In giving ourselves a complete government we affirm our existence as a separate nationality.”

In Canada East, the threat of American domination came into play. Cartier observed, “The question is reduced to this: we must either have a British North America Federation or else be absorbed into the American Federation.” Indeed, just as Confederation was becoming a reality, American expansionist designs included the purchase of Alaska from the Russians for US $7.2 million. American Senator Charles Sumner boasted that the purchase was “the visible step to the occupation of the whole North American continent.” Perhaps Confederation had arrived in the nick of time.

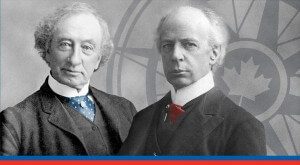

The final battleground for Confederation was England, where the Imperial Parliament would be asked to pass the British North America Act. But first, the “London Conference” was convened on December 4, 1866 to hold hearings on the matter. Macdonald was chosen conference chair. Sir Frederick Rogers of the Colonial Office commented on Macdonald’s mastery at nation-building. “Macdonald was the ruling genius and spokesman and I was very greatly struck by his power of management and adroitness…the slightest divergence from the narrow line already agreed on in Canada was watched for – here by the French and there by the English – as eager dogs watch a rat hole; a snap on one side might have provoked a snap on the other; and put an end to the accord. He stated and argued the case with cool, ready fluency, while at the same time you saw that every word was measured, and that while he is making for a point ahead, he was never for a moment unconscious of any of the rocks among which he had to steer.”

Despite Joseph Howe’s pleas to delay legislation until after the Nova Scotia election, the bill establishing Canada was first read in the British House of Lords on February 12, 1867 and passed four days later. Macdonald commented that the bill received the same consideration “as if it were a private Bill uniting two or three English parishes.” Nonetheless, the Colonial Secretary, Lord Carnarvon, remarked, “We are laying the foundation of a great State, perhaps one which at a future date may overshadow this country.”

In addition to being knighted, Macdonald was chosen by Queen Victoria, in advance of an election, to be Canada’s first prime minister. He was, of course, the logical choice. He had carried the day on matters of vision with abundant political skill. And his peers had chosen him to chair the London Conference. This latter choice was the test the Queen used to identify the man who possessed the confidence of a Parliament that did not yet exist. Being chosen prime minister before Canada’s first election gave Macdonald and his Liberal-Conservative colleagues an enormous advantage that they did not fail to exploit.

When John A. Macdonald was sworn in as Canada’s first prime minister on July 1, 1867, a national holiday was declared. But the slow and sometimes painful work of nation-building was only just beginning.

Bob Plamondon is a public policy consultant and author of The Truth about Trudeau, Blue Thunder: The Truth about Conservatives from Macdonald to Harper, and Full Circle: Death and Resurrection in Canadian Conservative Politics.