The government’s record after two-years in power has been a mixed bag, but overall is generally underwhelming, writes Sean Speer. It should use its remaining two years to move forward on several fronts.

The government’s record after two-years in power has been a mixed bag, but overall is generally underwhelming, writes Sean Speer. It should use its remaining two years to move forward on several fronts.

By Sean Speer, Oct. 3, 2017

Parliament’s return this month marks the nearly two-year point for the Trudeau government. It seems like only yesterday that the Liberals went from third-party status to majority government and were sworn in to enact its “real change” agenda. Much has happened since those initial days. Some expected. Some unexpected. It’s a reminder that statecraft is in large part controlled by exogenous forces and a four-year mandate can go by in a flash. Lofty rhetoric and good intentions will only get a government so far. Ultimate judgements rest on its record and results in an uncertain and evolving world.

How is the Trudeau government doing on this score? Has it delivered “real change”? These types of mid-term assessments tend to fall along partisan lines. There’s ample evidence – including positive economic growth and low unemployment on one hand, and stagnant business investment and declining manufactured exports on other hand – to form divergent answers to these questions. Political verdicts are invariably in the eyes of the partisan beholder.

This short essay does not aim to provide a definitive answer. But it does seek to test the government against its own stated objectives and the attendant policy recommendations that the Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI) put out in its Mandate for Change series in the government’s first 100 days. The outcome is a mixed bag. There has been some positive progress, some disappointments, and plenty of outstanding questions. The overall picture is generally underwhelming. Rhetoric and signalling has thus far mostly trumped positive action.

Mandate for Change

The Liberal Party won election in October 2015 with an ambitious message of “real change,” including with regards to middle-class opportunity, Indigenous empowerment, refugee settlement, climate action, health-care reform, pension modernization, and so on. Its ambition was a virtue rather than a vice. Canadians seemed drawn to Mr. Trudeau’s activist predisposition and his positive vision. But it was clear that the real question was whether the newly-elected government could translate its impulses and predispositions into concrete policies rooted in evidence. A mandate is one step. A governing plan is another.

MLI’s essay series, Mandate for Change, sought to help in this transition. The series took as its starting point the Liberal Party’s objectives in key areas. We then drew on the ideas and analysis of leading public policy thinkers including MLI Munk Senior Fellow Ken Coates, Canada Institute director Laura Dawson, and infrastructure policy expert Brian Flemming. The goal was to put forward clear, concrete recommendations that would make incremental progress in Ottawa’s key priorities. There were ultimately 14 essays, 12 authors, and more than 50 recommendations to deliver on a growing economy, rising living standards, a greener environment, and a new defence and security agenda.

Generally, the recommendations were received in the positive spirit in which they were conceived. This was not about relitigating the government’s mandate or priorities. It was about developing a set of policies that would increase the chances Ottawa would succeed in meeting its objectives. MLI authors were subsequently invited to parliamentary hearings, public roundtables with Ministers and MPs, and private meetings with public servants and political staff.

The 2016 and 2017 budgets and other government policy announcements saw some of our recommendations translated into action, including:

- Focusing on asset management plans at the local level to help ensure that public infrastructure spending is rational and productive;

- Restoring Parliament’s responsibility for approving government borrowing to improve the functioning of our democracy;

- New resources for basic infrastructure and early childhood learning in Indigenous communities to support Aboriginal opportunity;

- Increasing Old Age Security/Guaranteed Income Supplement as a targeted policy to help low-income seniors – particularly widows – cover their living costs.

- Placing an emphasis on private sponsorship in its refugee settlement policy;

- Expanding the Working Income Tax Benefit to reduce work disincentives for low-income Canadians;

- Revisiting the government’s plan to fully adopt the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and instead focusing on building on the current legal framework to bolster Aboriginal opportunity; and

- Maintaining the previous government’s changes to the Canada Health Transfer and calling for “structural reform” to improve the Canadian health-care system.

These examples represented progress on the government’s overarching goals. But, as you can see in the accompanying table (click here), there has been little movement on a number of MLI recommendations. The majority of them in fact remain incomplete and still relevant. The issues on the government’s desk continues to grow as well in light of new and emerging challenges such as the NAFTA renegotiations, instability in the Korean peninsula, and growing numbers of asylum seekers. MLI has sought to keep up. There have been several subsequent recommendations in MLI studies including with regards to tax reform, foreign policy, Cancon rules, the innovation file, an opportunities agenda (including for Indigenous peoples), and so on. It’s a target-rich environment, as we like to say at our Chapel Street offices.

Real Change versus Mandate for Change

How has the government performed in such an environment?

There have been some positive developments. For example, the new consolidated Canada Child Benefit and Canada Caregiver Credit are good steps in simplifying the previous mix of child-care and caregiving-related policies and ensure that public resources are dedicated to those who need them most.

Yet this should not overshadow areas of considerable disappointment as well. The timidity of the government’s tax reform exercise represents a missed opportunity that has only caused political conflict. An ongoing flippancy about deficit spending and debt accumulation is also a major cause for concern.

Then there is the matter of outstanding or unfulfilled promises. Sometimes these so-called “flip flops” or cases of inaction should be lauded, to the extent that they reflect a sensible departure from wrong-headed campaign promises. Electoral reform is a good example. Implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is another. We should praise cases where the government has rightly changed its mind in light of compelling evidence. Lamenting it as infidelity to past pronouncements only encourages bad policy outcomes.

Yet there is a growing sense that high-level principles and directional statements are wearing thin in certain areas, particularly Indigenous policy. The expectations game was always going to be a challenge for this government. But it has made things worse by a tendency to emphasize style over substance. The result is a growing number of media stories about frustration and disillusionment with Ottawa’s inaction on key files. It’s a reminder that the transition from an electoral mandate to a governing plan, with real-world trade-offs and exogenous forces, would be a challenge.

The good news is that the government still has two years left to make progress. It ought to use the fall session to begin to move forward on several fronts. A recent announcement on cultural policy is a good start. Similar ambition is needed in other areas if the Trudeau government is to deliver on its vision of “real change.”

Next Steps

The ongoing focus will likely be on (1) tax and fiscal policy, (2) climate change, (3) the Indigenous file, and (4) Canada-U.S. relations, with a particular focus on the NAFTA renegotiations. I’ll just briefly address the first one here.

Tax policy has suddenly risen to the top of the federal policy agenda in light of the brouhaha caused by the government’s small business tax changes. It’s counter-intuitive but Paul Boothe’s recent idea that it could prompt broader tax reform to balance out the controversial proposals is so crazy it may just work. The Department of Finance conducted a review of the federal tax system last year. The first step ought to be releasing the findings of the review including which tax expenditures are worth preserving, which should be reformed, and which should be eliminated outright, as MLI recommended in February 2017. The next is designing a revenue-neutral “tax swap,” whereby inefficient or ineffective tax expenditures can be eliminated in exchange for lower or flattened tax rates.

The ongoing budgetary deficit is also bound to remain a hot topic, notwithstanding recent news that the 2016-17 deficit was lower-than-projected. It will persist as an issue for two reasons.

The first is last year’s lower deficit was driven not by permanent savings but delays in infrastructure spending and it’s not as if this will produce a lasting improvement to the fiscal picture. This is especially the case since the Liberal Party platform raised this issue and promised that communities will not be “shortchanged.” It thus requires some cognitive dissonance on the part of the government to boast about its better-than-projected fiscal results and at the same time assure cities that the source of the improvement will not be “allowed to lapse.”

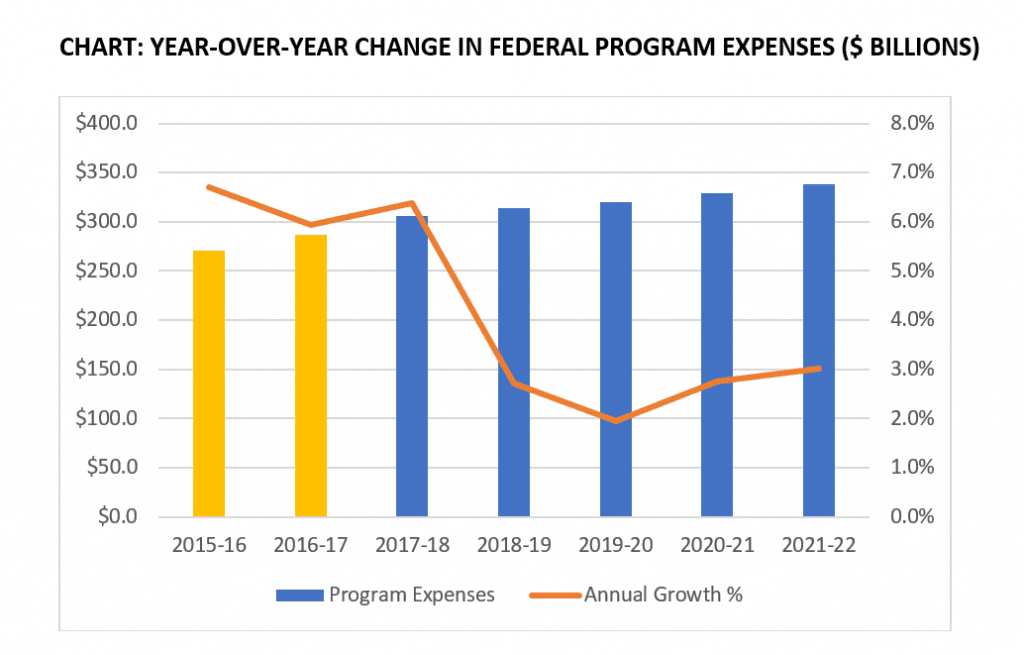

The second is that the government has still not set out its plan to restore budgetary balance. There’s good reason to believe that it will stretch out well beyond its current four-year mandate. Indeed, current budget projections still anticipate a significant drop in year-over-year spending growth with no explanation (see chart 1). The yellow bars represent final figures and the blue ones are projections. Does anyone really believe that annual program spending growth will fall from a two-year average of 6.3 percent to 3.7 percent in the final years of the mandate? The more likely scenario is spending growth remains strong or even grows due to reprofiling of infrastructure funding (to say nothing of electioneering) and in turn the budgetary deficit persists and risks growing. It’s important therefore that the Fall Economic Update finally set out a credible path to budgetary balance.

There will invariably be other issues that pop up in the next two years. That’s the nature of governing. But it’s important that the government begins to make greater progress on its key priorities. MLI will continue to provide support in the form of policy analysis and recommendations. It’s bound to remain a target-rich environment.

Sean Speer is a Munk senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.