Some recent commentary has urged calm about Canada’s federal finances following the 2016 budget, writes Sean Speer. And while it is true there is not an “imminent fiscal crisis”, it’s not unreasonable to question the utility of deficit spending or be worried about where the country is headed.

Some recent commentary has urged calm about Canada’s federal finances following the 2016 budget, writes Sean Speer. And while it is true there is not an “imminent fiscal crisis”, it’s not unreasonable to question the utility of deficit spending or be worried about where the country is headed.

By Sean Speer, April 5, 2016

Another federal budget has come and gone. While most Canadians have understandably moved on, economists and policy commentators continue to debate the Trudeau government’s fiscal policy. Budgetary deficits – nearly $120 billion and counting – are the budget’s signature policy and the source of ongoing contention.

The fiscal policy debate is manifested in an initial wave of commentaries such as “Canada is adrift without a fiscal anchor” and “Liberals’ budget hikes pressure on Canada’s dangerous debt bomb”, and a subsequent response in form of essays and columns such as “We are not heading to fiscal crisis” and “Deficit mania: stuck in the 1990s again”. Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s budget anticipated a multiplier effect. Presumably though he had not expected that it would come in the form of multiplying commentaries about his deficit spending.

Broadly speaking these post-budget analyses can be placed into two camps. The first is dubious on the utility and composition of the federal deficit and is concerned that the absence of a plan or timeline to eliminate the deficit could set the government on a path of protracted budget shortfalls. The second argues that the projected budgetary deficits are sustainable and that claims they may lead to long-run fiscal challenges are overblown.

To the extent that anyone is keeping track mark down another member for the first camp. Raising questions about the utility of budgetary deficits in a growing economy and the risks of ongoing deficits in the absence of a clear plan to balanced budget is hardly evidence of false alarmism. The onus of fiscal policy should be on those who support deficit spending rather than those who raise cautionary notes about the advisability, utility, and consequences of a return to budgetary deficits.

Dissuasion of hyperbole is fair enough. We are not on the cusp of an “imminent fiscal crisis.” Projected deficits as a share of GDP are lower than what we witnessed in the 1970s and 1980s. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to remain essentially flat over the next five years. No one is going to confuse Canada for a banana republic.

But one can accept that the budget’s return to deficit spending does not put the country at risk of “an imminent fiscal crisis” and still question its usefulness. Put differently: just because the federal government can run deficits does not mean it should.

But one can accept that the budget’s return to deficit spending does not put the country at risk of “an imminent fiscal crisis” and still question its usefulness. Put differently: just because the federal government can run deficits does not mean it should.

Part of the debate has focused on the extent to which a drop in federal revenues or a hike in spending have caused the deficit. The government cannot be faulted for the decline its revenue outlook. Federal revenue projections have fallen by an average of $7.2 billion annually relative to the previous year’s budget. This deterioration in federal revenues was bound to make it challenging to balance the budget this year.

But the Trudeau government cannot claim immunity on the magnitude and duration of the projected budgetary deficits. It was a matter of choice rather than circumstance, as National Post columnist Andrew Coyne has observed.

Consider 2015-16, for instance. Projected revenues are now higher than in the 2015 Budget and yet the government is anticipating a deficit of $5.4 billion rather than a surplus of $1.4 billion – a $6.8 billion swing that cannot be attributed to a drop in federal revenues.

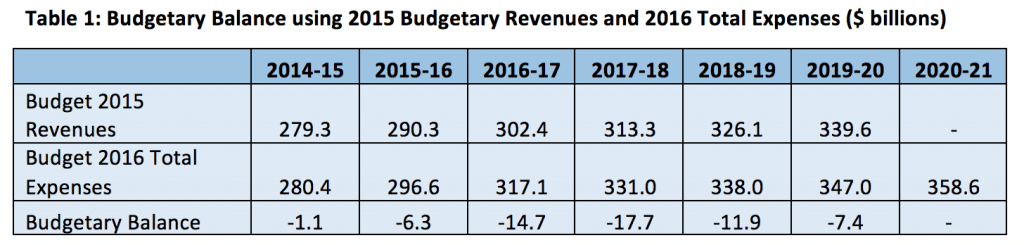

A similar story emerges when one unpacks the deficit projections in subsequent years. Remember the Trudeau government committed to annual deficits of $10 billion per year and now asserts that these deficits will be higher as a result of the deteriorating revenue outlook. One way to test this claim is a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the federal fiscal picture using revenue projections from the 2015 Budget and spending assumptions from the 2016 Budget. It is an imperfect calculation but it seeks to isolate the increase in federal spending from the drop in revenue to better understand the driver behind the rising deficit projections. Table 1 shows that the deficit is higher than the $10 billion cap that the government set for itself even before one accounts for the decrease in revenues relative to the 2015 Budget and this does not account for the $6 billion risk adjustment reflected in the 2016 Budget.

The point is that deteriorating revenues do not fully explain the government’s departure from its self-imposed deficit cap of $10 billion. Discretionary spending increases are a major source of the government’s budgetary deficits.

The composition of new federal spending is therefore worth examining. What is driving spending growth? Mr. Morneau’s speech cited “invest” and “investment” more than 40 times as the budget’s central idea. Its centrality to the government’s budget message should come as no surprise. The role of public investment in creating the conditions for economic growth has been a key part of its economic vision since last year’s federal election.

As a basic premise there are few who would contest that certain types of public spending are a critical input to economic activity. Public spending on core infrastructure – such as transit, roads, bridges, and highways – for instance is often considered “investment” to the extent that it lowers the cost of the movement of people, goods, and services in Canada and to external markets. To the extent that discretionary spending is in large part responsible for the return to budgetary deficits there may have been a case assuming that spending increases were focused on investment.

Yet it is difficult for one to argue that the increase in program spending was driven by public investment rather than current consumption. Of the $33.7 billion in new program spending over the next two years, less than one-third is dedicated to infrastructure. This percentage falls even further when one drills down into what the budget document characterizes as infrastructure. It requires a rather elastic definition of infrastructure, for instance, to consider “municipal capacity building” (referring to project management and infrastructure planning) as infrastructure or an investment.

Much of the new spending – and in turn the budgetary deficit – is focused on immediate consumption (that is, spending with little or no long-term return) such as seniors’ benefits and operating funding for the CBC. One might argue that some of these expenditures are not only justified but important for individuals, communities, and the country. Incremental funding to improve social services in Aboriginal communities, for instance, was overdue. But it is hard to rationalise government borrowing to pay for basic, present-day services. And it is equally difficult to contend that spending on current consumption is going to drive long-term economic growth. As BMO economist, Douglas Porter, has said:

“While there was much talk about enhancing productivity and growth, I’m afraid that most of the budget measures will just provide a one-off boost to spending, and not support longer-term activity. In fact, some may suggest that it did the opposite, since the near-term deficit boost at some point will have to be repaid.”

Yet the government continues to claim that its deficit spending focused mostly on current consumption will somehow drive economic growth – that is, it will contribute to greater economic activity in the short- and long-term term. The message has become a bit muddled in light of recent positive economic developments but the key takeaway seems to be that more spending is justifiable irrespective of the state of economy and whether one’s focus is the short- or long-term.

There are basic theoretical problems with the idea that a smattering of new spending will produce the economic growth that the government is anticipating especially when one considers that the economy is already growing and the extent to which higher spending is titled towards consumption. Expectations that the budget will therefore “kick start” the economy are likely to be misplaced.

As for the path to a balanced budget, the 2016 budget is essentially indeterminate. The budget document states: “the Government will set a timeline for balancing the budget when growth is forecast to remain on a sustainably higher track.” It is the first federal budget since the 1990s that envisions deficit spending over the entire fiscal planning period with no prospect of returning to a balanced budget. Post-budget comments from the prime minister and the minister of finance have suggested that deficit spending will continue for at least half-a-decade and possibly longer.

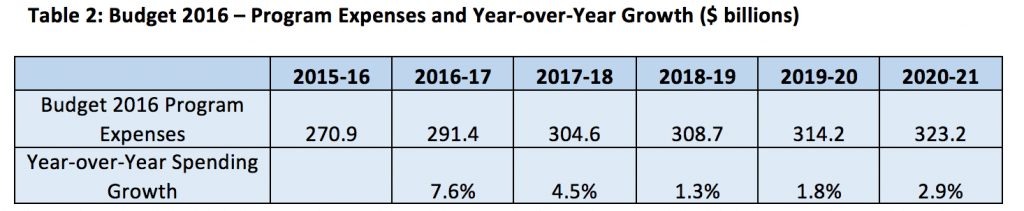

It is quite conceivable that the budgetary deficit will persist for the foreseeable future. Consider that current projections for program expenses anticipate that year-over-year spending growth will fall from 7.6 percent in 2016-17 to 1.3 percent in 2018-19 (see table 2). This represents optimistic (and likely unattainable) budget planning.

There is little in this year’s budget – including the intention to repeal its predecessor’s Balanced Budget Act – to signal that the government will impose the type of fiscal discipline necessary to bring annual spending growth down to this level. Quite the opposite. The reintroduction of the Labour-Sponsored Venture Capital Tax Credit in spite of clear evidence of its deficiencies, reversal of the increase to the Old Age Security eligibility age, and ceasing the reforms to sick-leave benefits give reason to doubt the government’s willingness to make tough fiscal choices. There is every reason to believe that annual spending growth will rise faster than projected especially since several big-ticket promises, such as increasing the Canada Health Transfer, are still outstanding. It is quite possible therefore that medium-term fiscal projections deteriorate rather than improve.

Does this signal an “imminent fiscal crisis”? Of course not. The deficit as a share of GDP is low relative to historical experience and the federal debt-to-GDP ratio is steady. But it does mean that we may be entering a period of ongoing budgetary deficits that are primarily driven by spending increases on current consumption and are indifferent to the state of the Canadian economy.

It also creates the risk that the federal government may fall into a cycle of ongoing deficit spending that is challenging to extract itself from. Consider that Canada has experienced an economic slowdown or recession, on average, every eight years since 1980. An economic recession squeezes federal revenues and increases spending in the form of automatic stabilizers such as employment insurance. It also may lead to discretionary spending increases to stimulate economic activity as we witnessed in 2009-10 and 2010-11.

Drawing on past experience, analysis by the Fraser Institute shows that Canada will likely experience an economic slowdown or recession over the next two or three years. An unexpected economic shock would undermine the government’s fiscal planning and almost invariably extend the current string of budgetary deficits.

Would such a scenario precipitate a fiscal crisis? Still no. But one can begin to discern how easy it is for a government to lose control of its timetable for a balanced budget and for deficit spending to become normalized and difficult to cease. This is presumably a scenario that most, if not all, economists and policy commentators would agree that the government ought to avoid.

The solution, then, is not alarmism (to the extent that anyone can be accused of raising alarms) but it is also not complacency, as Coyne has recently put it. The government needs to put forward a clear plan to erase the budgetary deficit. This does not necessarily mean closing the revenue gap in a single year or abandoning its campaign commitments. But it does mean a clearer articulation of how and when the federal government should run budget deficits (calls for deficits every time there is an adjustment in global markets or negative economic news risks intellectualizing irresponsibility) and concrete steps to eliminate the current deficit over the medium term.

This is the best path to ensuring that federal finances remain sustainable and that those voices cautioning calm in the face of the current string of budgetary deficits are ultimately proven right. Until then the debate about the Trudeau government’s fiscal policy is bound to continue.

Sean Speer is a Senior Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute