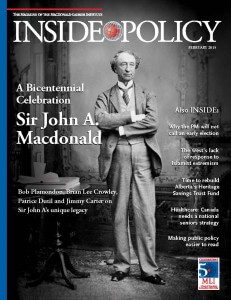

In the Feb. 2015 edition of Inside Policy, the magazine of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, a  strategic affairs and public policy advisor Andrew Rodych cajoles bureaucrats to rid government laws and regulations of overcomplicated language.

strategic affairs and public policy advisor Andrew Rodych cajoles bureaucrats to rid government laws and regulations of overcomplicated language.

By Andrew Rodych, Feb. 13, 2015

“If you can’t understand it, you can’t change it,” says Eric Evans, author of numerous books discussing how to address complexity within software code. In the arena of public policy, it is no different. Even if citizens are given all the tools available to make policy change, it means nothing if they cannot understand the policy itself.

A lack of citizen understanding of policy leads to an inability to move forward with change, and consequently, a lack of engagement from the citizenry in the policy development and overall political process. Not understanding the policy or politics of their country can lead the citizenry to apathy in large numbers.

This concept seems intuitive. As an analogy, one can look at sports. If you enjoy sports, you do so because you understand the game. You engage in the sport, either by participating or as a fan, because you understand the rules—the scoring system, the field structure, the actions of the players and so on.

In Canada, many citizens enjoy hockey. Let us assume you are one of those hockey-loving citizens. If you were to go watch Australian Rules football or Russian Lapta there is a good chance your engagement in the sport, your desire to play or even simply continue viewing the event, would be quite low if you did not understand the rules.

The problem of policy literacy for most citizens arises from a growing complexity within that very policy. The apathy in the political arena, within the political process and policy development, partly stems from not being able to read and interpret the rules. Many citizens are watching a game they do not understand. Two of the major elements of this problem are length and word choice.

If we review word count, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms has 2,609. The By-law Concerning Towing in La Ville de Montreal has 4,225 words. The Alberta Personal Directives Act is 6,324 words long. The Parliament of Canada Act has over 20,000 words; the Income Tax Act has over 1,000,000 words.

If the Charter, which assures the rights and freedoms of all Canadian citizens, can be written in under 3,000 words, it is hard to imagine why a by-law on towing cannot be shorter. The policy for income tax could surely be more concise and easy to understand.

Wordiness makes sentences difficult to read. To the reader, the large number of words makes comprehension laborious. It discourages them from reading and trying to understand the content. Even worse, wordiness can make sentences seem to contradict themselves. Some readers will become distracted or fail to understand the purpose or connection between sentences, especially with multiple references to other sections within the same policy. The whole topic of a section can be lost. Too many words can create confusion instead of clarity.

Word count is not a perfect measurement. More words do not necessarily mean more confusion. However, there is a difference between elaboration and complication. Using more words to better describe concepts within a policy is acceptable as long as this description creates ease in understanding and makes application of the policy easier.

Not only does the length of policy make it inaccessible to many citizens, but also the level of writing is an issue. Specialized words fill policy and regulation; these words are jargon and other technical terms.

Terminology also becomes more troublesome when we look at definitional misunderstand of “direction words” – the lack of clarity around words such as “should, shall, must, can, require.” The use of direction words needs to clarify what is an unavoidable requirement and what is just a goal of the policy.

So the challenge is finding a means to make policy literacy easier, and hopefully engagement more meaningful. If the twofold problem above exists, the solution should be the two-part action of both reducing the number of words and using simpler ones. However, both politicians and legislative drafters need more guidance to improve policy readability.

A first step would be looking back at the essay, “Politics and the English Language”, by George Orwell. Within the essay, Orwell assesses the poor English used in politics. He wrote out six rules of the English language (which would apply to the French language equally) he believed would provide more clarity in political discourse. These rules should also translate to the policy that develops from those politics. The rules are:

“(i) Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. (ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do. (iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. (iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active. (v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. (vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

Even Orwell was not perfect in following these rules, but they are a fine base to build from. Alan Siegel, the well-known communications consultant, presented an entire TED Talk on simplifying legal jargon and wrote a book, Simple: Conquering the Crisis of Complexity, about reducing the complexities that continue to grow around us. He argues we use plain language and remove the unnecessary jargon. That solution may seem challenging as some may question the definition behind “plain language.” Yet, there are multiple resources that can assist in translating overly complicated text into plain language.

Software, including the most basic of word processors, includes functions that allow the writer to assess the reading ease and reading level of text. Grammar checking functions can help writers identify and remove passive, long, and overly wordy sentences. The Silicon Valley age is starting to produce even more breakthroughs in language simplification. Simplish.org is online software that will take technical texts and translate it into plain language (or Basic English according to its classification), as well as summarize text. Technology can make policy simplification less difficult.

Other less technological methods could include using writing style guides (many available free on the internet) which provide plain language guidelines and word options. In an example from a Dictionary of Plain English, instead of using the word “constitute,” one should use “make up.” Another example, instead of the word “materialize,” one should use “appear.”

There is no easy solution for simplifying public policy, and much of policy to date, whether legislation, regulations, frameworks, or guidelines would be tedious and sometime legally challenging to update. These concepts are applicable for some past policies through amendments. However, the larger opportunity presented by the simplifier concepts above is for politicians and legislative drafters to start using it on new policy.

By using plain language rules, and being willing to review, edit, and focus one’s writing, simplification of policy occurs. According to the word processor used to type this article, the word count is 1518; I used zero passive sentences, and it has a Grade 11 level-reading ranking.

Wordiness, which provides better description, and jargon which is necessary due to technical correctness, will both remain in policy. By simplifying policy, one is not “dumbing it down” or trying to reduce its effectiveness. Instead, we need to simplify to create accessibility.

There is a circular dilemma present in trying to move towards simpler public policy. Arguably, the best measure to direct the creation of simpler policy would be a policy itself. For citizens to be better engaged though, they need to understand the policies that currently exist and how to get involved in the development process. They need an understanding of how to engage their elected officials to make policy simplification a priority.

Currently, the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada discusses plain language as a goal. Not released as of yet is a proposed guide on plain language referenced at the end of that policy. Such a guide should consider Orwell’s rules, but should also look at other jurisdictions’ work on simpler language for their laws.

In the US, the Plain Writing Act of 2010 was a policy step in the right direction. Cass R. Sunstein, the author of Simpler: The Future of Government and former head of the US Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, argues for a continued focus on plain language summaries where it is not possible to write policy fully in plain language. Further, such summaries should include the primary requirements or rules of any policy and the legal authority behind that policy.

Articles like this one may help raise awareness of ways to create that simplification, however, other efforts will be required to get the types of solutions presented implemented. Maybe in the end, the easiest way to start the process of change is to test politicians and legislative drafters to consider their reputations and own understanding when writing policy by taking to heart the quote attributed to Albert Einstein, “If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” As such, if they cannot write public policy simply, maybe they do not understand their policy intentions and goals well enough.

Andrew Rodych is a strategic issues and public policy advisor with an environment and energy services company based in Alberta. With a background in both the public and private sectors, he provides strategic advice and systems support alongside policy research, stakeholder engagement, and communications planning. Andrew sits on the Calgary Chamber of Commerce Tax and Economic Affairs Committee and gives his time to multiple political endeavors. He has a Master’s degree in Public Policy from the University of Calgary.