This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Peter MacKinnon, November 6, 2024

Toronto Metropolitan University’s new medical school admissions policy has taken race discrimination to a new level: straight white males will not be eligible for 75 per cent of its seats. These will be reserved for Indigenous, Black, 2SLGBTQ+ and other equity-deserving students for whom admissions criteria will be relaxed.

The new medical school has been hailed by university president Mohamed Lachemi as an initiative that will “disrupt and drive change within the health-care system,” and by medical school dean Teresa Chan as one that “will provide a supportive and inclusive process” for equity-deserving groups.

It will also discriminate — extensively — against white male students who would otherwise compete under admissions criteria — high or relaxed.

The story of how we got here is not a new one. Canada constitutionalized affirmative action in Section 15(2) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and it has been widely interpreted and practiced to the point that it narrows the scope of the fundamental principle of non-discrimination set out in Charter Section 15(1): Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age, or mental or physical disability.

But — universities have declared — the charter applies only to governments; it does not apply to them, leaving them free to do what they like in processes that would otherwise attract charter scrutiny. The better argument is that, in addition to governments, the charter applies to activities of non-governmental institutions that are governmental in nature, a prime example being post-secondary education. Even if applicable to universities, however, the wide practice of affirmative action said to be permissible under Section 15(2) undermines the 15(1) principle of non-discrimination.

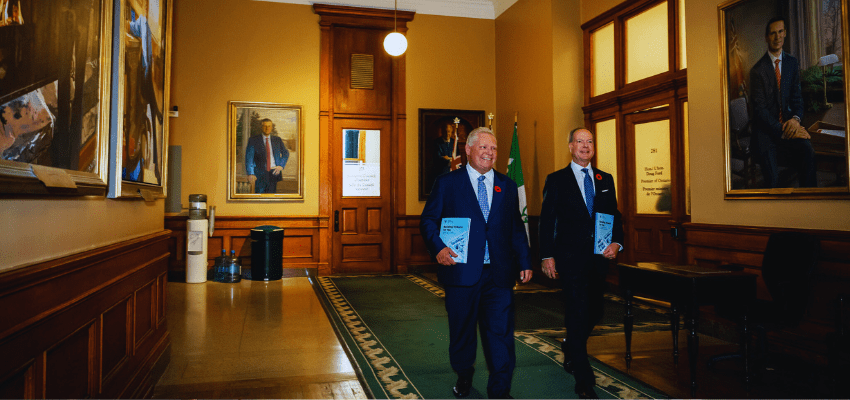

This happens in the name of equity, diversity and inclusion, a benign sounding phrase until we explore the inequalities and exclusion that it produces. Canadians are beginning to pay attention to these impacts and many disapprove. That is why they will be pleased by the Ontario government’s pushback on TMU’s medical school admissions policy. Premier Doug Ford is insisting that the new school must educate qualified persons “regardless of their race or background.”

TMU would be unwise to ignore this admonition. Governments can and should withhold funding from institutions that do not comply with the principle of non-discrimination.

The Ontario government’s approach should be followed across the country. The first principle is non-discrimination as set out in Section 15(1). Affirmative action permitted by 15(2) should be strictly interpreted so as not to unduly interfere with that principle.

In 2023, the United States Supreme Court revisited affirmative action and declared it unconstitutional because universities did not honour limits on the practice that were previously laid down by that court. Declaring affirmative action unconstitutional is not an option in Canada but that does not prevent an insistence on honouring the first principle set out in 15(1) and requiring reasonable limits to affirmative action that are overseen by governments and the courts.

Peter MacKinnon has served as the president of three Canadian universities and is a senior fellow of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.