This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Dave Snow, October 16, 2024

After Jagmeet Singh “ripped up” the Liberal-NDP supply-and-confidence agreement (SACA) last month, political posturing over non-confidence motions has become a frequent parliamentary spectacle. The Conservatives have already tabled two non-confidence motions in recent weeks, with the promise of many more to come. Amidst this overheated political debate, however, we have failed to situate the non-confidence vote in its historical context.

To find out more, I analyzed how non-confidence motions—and opposition motions overall—have been used over the last 20 years in Parliament.

While non-confidence motions have been rare, opposition motions have long been a weapon in Pierre Poilievre’s parliamentary arsenal, both before and after he became Conservative leader.

Given the new instability of the post-SACA Parliament, it is now not surprising that non-confidence motions—the ultimate opposition motion—have become Poilievre’s new weapon of choice.

Non-confidence motions are rare but travel in packs

Canada’s parliamentary system of responsible government operates according to the “confidence convention,” whereby the government must govern with the support of a majority of the members of Parliament (MPs) in the House of Commons. When the government loses the confidence of the House, the prime minister must by convention resign or request a new election. The House can express its lack of confidence in the government via a response to a throne speech, by voting against a budget, or by supporting a motion of non-confidence.

Non-confidence motions make up a very small proportion of all motions, which are proposals introduced by MPs requesting “that the House do something, order something done, or express an opinion with regard to some matter.”

Motions from opposition parties are typically tabled on “opposition days,” which are allocated to official parties proportionate to their number of MPs. Most successful opposition motions do not actually require the government to act—they are merely “a declaration of opinion or purpose.” Successful non-confidence motions, by contrast, typically result in an immediate election.

Using House of Commons data, I analyzed every opposition motion, including non-confidence motions, from the 38th Parliament (Paul Martin’s 2004–2005 minority) until Oct. 4, 2024.

Excluding amendments, there have been 380 unique opposition motions, which ranged from zero in the short-lived first session of the 40th Parliament (the 2008 “coalition crisis”) to 81 in the first and only session of the 42nd Parliament (Trudeau’s 2015–2019 majority).

Non-confidence motions in the House of Commons are rare. There have only been nine since 2004 and only two of those were successful, resulting in the 2006 and 2011 elections. As leaders of the Official Opposition, neither Stéphane Dion (2006–2008), Tom Mulcair (2012–2015), Andrew Scheer (2017–2020), nor Erin O’Toole (2020–2022) introduced one—although Dion had planned to before Harper prorogued Parliament in 2008. Between 2011 and 2024, nearly 13 years had passed without a motion of non-confidence.

That all changed with three (and counting) non-confidence motions from the Poilievre Conservatives since March 2024. This proliferation of non-confidence motions has historical precedent. Over the course of 64 days between March and May 2008, the NDP introduced three straight motions of non-confidence in the Harper government. Stéphane Dion’s Official Opposition Liberals, who did not want an election at the time, opposed one motion and came down with a case of “diplomatic flu” for the other two, with only 10 and 20 of the approximately 100 Liberal MPs showing up to support those motions. In all three cases, the Harper government survived, just as the Trudeau government has thus far.

Opposition motions have been much less successful since 2021

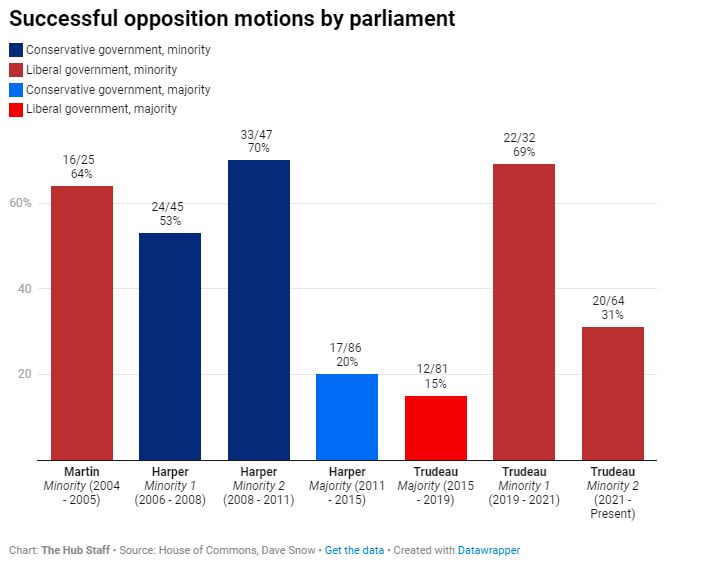

Non-confidence motions have only comprised 2 percent of all opposition motions, but the other 98 percent tell us a great deal about how Parliament functions. Opposition motions were slightly more successful during the Harper Conservative government (42 percent) than the Martin and Trudeau Liberal governments (35 percent), but the major difference is, unsurprisingly, between majority and minority governments. As the graph below shows, only 20 percent of motions passed during Harper’s majority (2011-2015) and only 15 percent during Trudeau’s majority (2015-2019).

Minority governments have been a different beast—until recently. Opposition motions had a high success rate during most minority governments, with success rates of 53 percent (Harper 2006–08), 64 percent (Martin 2004–05), 69 percent (Trudeau 2019–21), and 70 percent (Harper 2008–2011). However, this has dropped to 31 percent during the most recent Trudeau minority (2021–present). In terms of opposition motions, the current Parliament looks more like a majority than a minority.

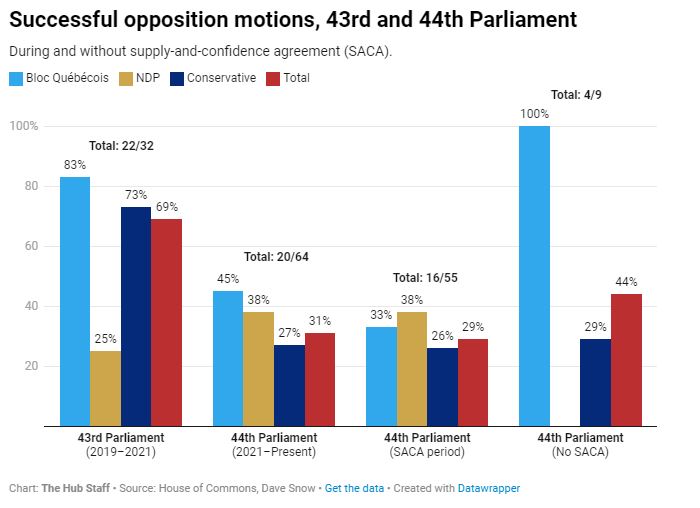

What changed? Not the makeup of the House of Commons: the 2021 election results were nearly identical to 2019. One possible explanation is the existence of the Liberal–NDP supply-and-confidence agreement (SACA), which ran from March 22, 2022 until Sept. 4, 2024. Although the SACA did not commit the NDP to defeating opposition motions (other than those involving confidence), it may have facilitated a de facto Liberal–NDP alliance on these motions. To explore this, I analyzed opposition motion voting records for the four major parties during SACA, a period where 55 motions were introduced and 16 passed (a 29 percent success rate).

Three things stand out from the results. First, party discipline within the four major parties is very strong, even on opposition motions. Across the 55 opposition motions during SACA, there were only two occasions when more than a single MP dissented from the party line. This included when three Liberals voted against an NDP motion calling for a ceasefire in the Middle East and when the NDP MPs split on a failed Bloc Québécois motion to abolish the monarchy.

Second, the NDP was indeed the party most likely to side with the Liberals. Those two parties voted together on 38 of the 55 SACA-era motions (69 percent of the time). The Liberals voted with the Bloc 56 percent of the time and with the Conservatives only 18 percent of the time. Interestingly, the most common voting “coalition” was actually the NDP and the Bloc, who voted together 71 percent of the time.

Third, the Conservatives were most often on the outside looking in. During the SACA, the Liberal–NDP–Bloc voted en bloc against the Conservatives 44 percent of the time (24/55), whereas the Conservative–NDP–Bloc only voted against the Liberals 16 percent of the time (9/55). This was a complete inversion from the previous Parliament (2019-2021) when all other parties voted against the Liberals 44 percent of the time (14/32) and the Conservatives 16 percent of the time (5/32).

During the SACA, 7 percent of votes involved the NDP versus all other parties (compared with 9 percent in the previous Parliament), while Bloc MPs never voted completely alone.

The combination of all these factors—strong party discipline coupled with the Liberals often forming a voting majority with the Bloc and/or the NDP—has led to diminished opposition motion success during the SACA period. The above graph shows a considerable drop in the success of Conservative motions (from 73 percent to 26 percent) and Bloc motions (from 83 to 45 percent), between Prime Minister Trudeau’s first and second minority, including during the SACA. Although the Liberals are in government, the Conservatives face the strongest opposition in the House.

Pierre Poilievre: leader of the Official Opposition (motion)

Clearly something changed during the most recent Parliament that has made the other opposition parties less likely to support Conservative motions. Part of the answer can be explained in two words: Pierre Poilievre.

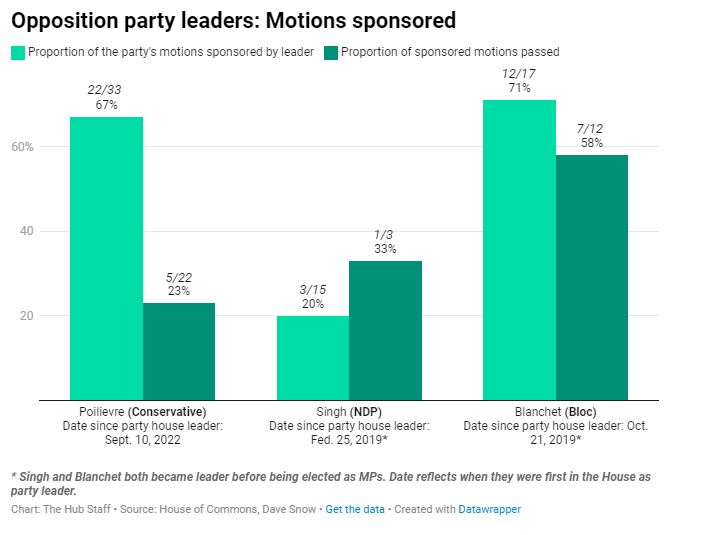

In the 44th Parliament, Poilievre has sponsored a total of 22 opposition motions—more than one-third of all motions (34 percent) and nearly half of those sponsored by the Conservative Party (49 percent). Since he became Conservative leader, Poilievre has introduced 67 percent of Conservative opposition motions. When Poilievre sponsors a motion, it is more likely to be defeated. Only 23 percent of Poilievre’s motions have passed during the current Parliament, compared with 30 percent of motions sponsored by other Conservative MPs. Since he became leader, 55 percent of Poilievre-sponsored motions have been opposed collectively by the Liberal–NDP–Bloc, compared to 45 percent of other Conservative-sponsored motions. The mere presence of Poilievre as a sponsor both reduces other parties’ support and reduces the likelihood of passage.

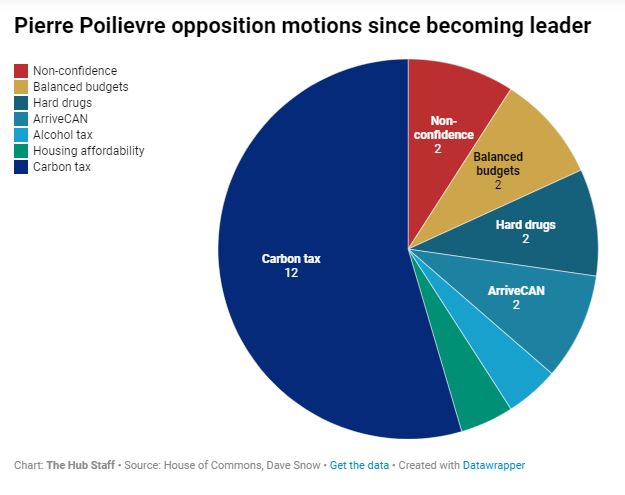

What do Poilievre’s opposition motions contain? A nearly single-minded focus on the carbon tax. Of the 22 motions Poilievre has sponsored since becoming Conservative leader, 12 have been about the carbon tax, with most asking the government to repeal or delay the tax (this is in addition to one of Poilievre’s non-confidence motions, which called for a “carbon tax election”). Poilievre’s other opposition motions have been firmly on brand with his major priorities: rejecting the legalization of hard drugs, balancing the budget, lowering taxes, increasing housing supply, and addressing government mismanagement (with respect to the ArriveCAN scandal).

These opposition leader priorities stand in stark contrast to Poilievre’s predecessors. As Conservative leader, Erin O’Toole only sponsored three opposition motions (on COVID-19 vaccine distribution, on an anti-corruption committee following the WE Charity Scandal, and on a committee to study the fall of Afghanistan), while Andrew Scheer only sponsored two (on MPs repaying taxpayers when they violate the Conflict of Interest Act and the on a committee to study the SNC-Lavalin Affair). None of these issues were lasting political priorities for O’Toole or Scheer.

Poilievre also viewed opposition motions as a useful tool prior to taking the helm of the Conservative Party. Between March 2017 and December 2020, he sponsored 14 opposition motions, half of which concerned the carbon tax (13 of 14 were defeated, including all seven on the carbon tax). Poilievre has been beating the carbon tax drum for some time now.

Poilievre is bringing forward opposition motions more than his predecessors. During the previous minority Parliament (2019–2021), Conservative leaders only sponsored 9 percent of Conservative motions. Harper only introduced 29 percent of Conservative motions during the 2004–2005 Martin minority.

Meanwhile, NDP leader Jagmeet Singh has only introduced three of the NDP’s 15 opposition motions (20 percent) during his five-plus years in the House of Commons. The one leader who has shared Poilievre’s preference for the opposition motion spotlight is Yves-François Blanchet. The Bloc leader has introduced 71 percent of his party’s opposition motions since being elected. Unlike Poilievre, however, Blanchet’s motions—ranging from reviewing federal immigration targets to affirming provinces’ ability to use the notwithstanding clause to calling for the federal government to stop investing in fossil fuels in order to combat climate change—have not been as unified in their messaging.

Setting the Parliamentary agenda

I draw three main conclusions about opposition motions. First, while non-confidence motions are rare, there is recent precedent for their frequent use as a temporary political tactic. The Conservatives’ recent flurry of non-confidence motions mirrors a similar burst from Jack Layton’s NDP in 2008. In each instance, the party leader used non-confidence motions from a position of political strength to dare the weakened opposition parties—Dion’s Liberals in 2008; Singh’s NDP in 2024—to support the government.

Second, opposition motions reveal another way in which the current Parliament has operated more like a majority than a minority government. During most minority governments, opposition parties typically unite to pass opposition motions against the government. But in the current Parliament, it has been far more common for the governing Liberals to unite with the NDP and/or the Bloc to oppose the Conservatives. This left-of-centre unity cannot be explained by mere ideological disagreement (which existed during the previous Parliament) or by the SACA (which did not require the NDP to vote with the government on opposition motions, just non-confidence motions). Instead, it could reflect the progressive parties’ desire to oppose the increasingly popular Poilievre Conservatives, by voting against motions sponsored by Poilievre himself.

Finally, opposition motions are yet another way in which Poilievre is doing politics differently from his Conservative predecessors and other party leaders. Both before and during his leadership, Poilievre sponsored opposition motions with the highest frequency of any MP from any party. His motions are relentlessly on message, with the carbon tax as his main target. Compared with other parties and even other Conservative MPs, his motions are less likely to pass the House and less likely to receive support from other parties. On paper, his inability to achieve support from the progressive parties could be seen as a failure. But I suspect Poilievre wears it as a badge of honour.