This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Jon Hartley, March 1, 2024

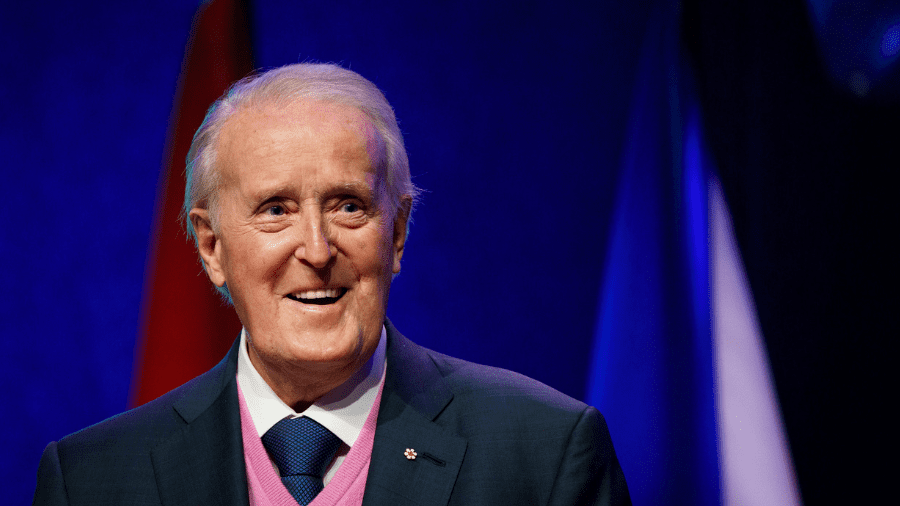

Brian Mulroney’s death on Thursday marked the passing of one of Canada’s greatest prime ministers. Mr. Mulroney was akin to Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in Britain in championing the cause for freedom. Perhaps his most memorable achievement was being the first prime minister to lead what I like to call a pro-growth policy agenda in Canada.

More specifically, Mr. Mulroney was unabashedly pro-freedom in terms of the markets. He vehemently fought against everything the Cold War enemy, the juggernaut Soviet Union, fostered, including its socialist ideas about domestic economic policy. Mr. Mulroney ultimately triumphed with a message of free enterprise, competition and innovation.

The Mulroney free-enterprise legacy is not perfect, to be sure. The GST that his government had introduced, while less harmful to economic growth than taxes on income, ultimately added to the Canadian tax burden. Mr. Mulroney’s seriousness about fiscal responsibility to keep Canada competitive was terrific but perhaps not enough to prevent the fiscal challenges that would occur later in the 1990s.

But these blemishes are small compared with an enormous legacy that had set the foundations for Canada’s prosperity today.

How did Mr. Mulroney come to embrace such a philosophy of free enterprise? Mr. Mulroney saw free enterprise as a mechanism for economic mobility. It was arguably the free-enterprise system that enabled him to come up in the world. He had gone from having very little growing up as the son of an electrician to becoming president of the Iron Ore Company of Canada in 1977 while still in his thirties.

Before Mr. Mulroney took office in 1984, things were looking bleak for Canada’s economy. In the early 1980s, inflation was surging and real incomes were falling in Canada. The economic conditions were so terrible that then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau appointed the Macdonald Commission to make policy recommendations.

The report was received by Mr. Mulroney in 1984 shortly after taking office, and included a recommendation to reach a free-trade agreement with the United States. Before NAFTA, the Liberal Party from the 1930s to the 1980s had negotiated a number of bilateral trade agreements with the U.S., slowly reducing tariffs. In the 1980s, many were opposed to the market-oriented reforms of the Macdonald Commission, including some in the Progressive Conservative Party of Mr. Mulroney.

This did not hold Mr. Mulroney back. His actions would culminate in the greatest part of his legacy: advancing the Canada-U.S. free-trade agreement (later expanded into the North American free-trade agreement with the inclusion of Mexico). Negotiating such an agreement was a bold move at the time, signalling Canada’s openness to the global economy and its willingness to embrace free-market principles.

NAFTA facilitated unprecedented economic growth by expanding Canadian access to the vast American market but also served as a catalyst for economic restructuring. While NAFTA is often criticized now amid the current populist upheaval against trade, the updated version, the USMCA, signed into law in 2019, is not much different.

Critics often point to drawbacks of free-trade agreements, such as negative effects on domestic manufacturing and employment, while overlooking the long-term benefits such as increased competitiveness and cheaper imported goods which provide great value consumer to everyone, especially those on lower incomes.

Mr. Mulroney’s free-enterprise philosophy was also heavily committed toward deregulation and privatization. His government privatized several major Crown corporations, including Air Canada and Petro-Canada, further encouraging private-sector investment and innovation. Canadians now have cheaper air fares and gasoline in part because of the privatization efforts conducted decades ago.

Mr. Mulroney also led a free-market approach to environmental policy. The 1991 Canada-United States air-quality agreement committed the two countries to significantly reducing emissions of pollutants that cause acid rain and contribute to smog. The solution devised by the governments of Mr. Mulroney and president George H.W. Bush was one of the first systems of “cap and trade,” capping the amount of pollution companies could emit and enabling them to trade their rights to pollute. The idea of using competition and market mechanisms to defeat acid rain was highly successful and would ultimately prove to be a great example of a conservative approach to environmental challenges.

Sadly, Mr. Mulroney’s death marks the end of a certain vintage of deeply free-market conservative politicians, including Mr. Reagan and Ms. Thatcher, who were similarly deeply committed to free-enterprise principles and advancing economic freedom around the world.

Jon Hartley is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a research fellow at the Foundation For Research on Equal Opportunity.