This article originally appeared in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, May 10, 2023

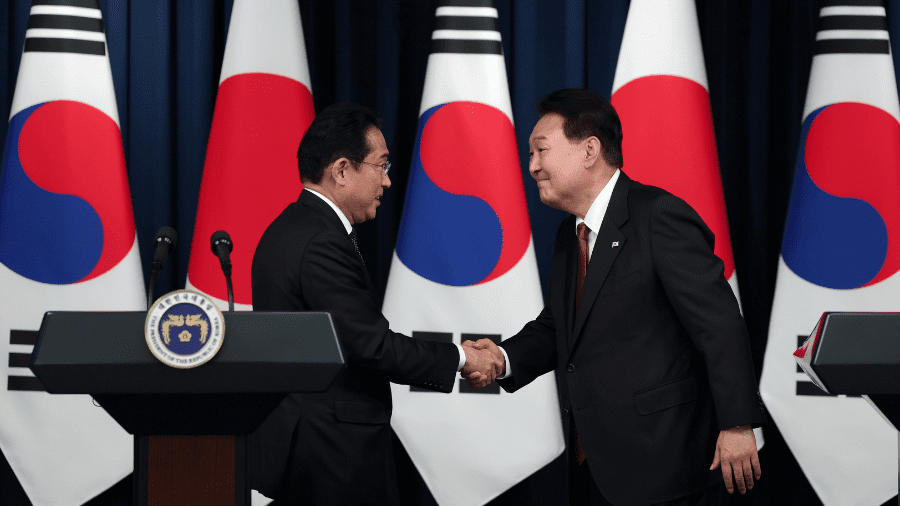

The strategic importance of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s visit to South Korea to meet President Yoon Suk-yeol cannot be overstated.

The meeting has the potential to set the tone for the future bilateral relations between the two nations, trilateral cooperation with the U.S. as well as for the wider geopolitical landscape of the Indo-Pacific.

Before coming into power, Yoon made it clear that he wanted to return the South Korea-Japan relationship to a more pragmatic and mutually beneficial relationship. He did this by first stating that the December 2015 “comfort women” agreement would be official government policy. He also visited Japan to meet with counterparts to discuss his new vision for South Korea-Japan relations.

Since becoming president, he has initiated many policies including the Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region, shown interest in participating in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (“the Quad”) between Japan, Australia, India and the U.S., and most recently, made a statement where he noted the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait, which predictably raised the ire of Beijing.

These are in line with Japan and like-minded states thinking about the long-term challenges in the Indo-Pacific including the importance and destabilizing nature of the current trajectory of China.

Of great significance, he visited Tokyo in March, the first visit of a South Korean leader in more than a decade to not only share omurice, a Japanese omelet dish made with fried rice, but to reset the relationship between Japan and South Korea that has been fraught with tension in recent years, particularly over historical issues related to Japan’s colonization of Korea in the early 20th century.

The icy relations have spilled over into economic and security issues and have threatened to undermine the stability of the region. Key examples include but are not exclusive to South Korea being excluded from Tokyo’s whitelist of trusted trading nations in August 2019 and South Korea, under the Moon Jae-in administration, threatening to withdraw from the volunteer intelligence-sharing General Security of Military Information Agreement.

Through this highly politicized period, the Japan-South Korea relationship, despite its complementariness, did not serve either country’s national interests.

It also made trilateral cooperation with the U.S. problematic. Intelligence-sharing, joint maritime training, a shared approach to managing North Korean missile and weapons of mass destruction proliferation and other issues critical to the region such as cross-strait relations, stable sea lines of communication in the East and South China Seas and cooperating on dealing with China all suffered.

Kishida’s visit to South Korea was an opportunity to continue to build upon the political capital spent by Yoon to reset this relationship and move toward a more cooperative and stable future. It was a chance to build bridges and find common ground on issues of mutual concern such as North Korea’s nuclear program, regional security and economic security.

The ongoing dispute about compensation for Korean forced laborers during Japan’s colonial rule will continue to drive a wedge between both countries. So will the issue of comfort women, those girls and women who suffered under Japan’s military brothel system before and during World War II. Both issues have been resolved legally and in the form of bilateral political agreements over the years. The moral responsibility, however, remains to be addressed sufficiently in Japan.

Kishida and other politicians in Japan need to demonstrate that at the leadership level, there is a consistent message about the colonial past. Kishida’s visit to the National Cemetery in Seoul to lay flowers and his declaration that his administration stands by the statements of past Japanese governments that have expressed their apologies for Japan’s colonial rule are important gestures.

Equally meaningful was a personal statement related to the colonial period that his “heart aches by the fact that many people suffered and felt sadness under the harsh environment at the time.” More could and should be done, but as former Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott said to China’s former premier, Li Keqiang, in late 2014, “history is a good teacher but a bad master.”

The incremental trust-building that Yoon and Kishida are displaying with their shuttle diplomacy may be the right formula for building a sustainable relationship without forgetting the past.

Kishida’s visit to Seoul, the invitation of Yoon to the Group of Seven Summit in May and a planned trilateral meeting between Japan, South Korea and the U.S. all suggest that the Japanese prime minister wants a more pragmatic relationship with Seoul that goes beyond bilateral ties. By inculcating Seoul in a web of minilateral and multilateral partnerships to deal with the imminent challenges facing the region, Kishida is creating platforms for Seoul and Tokyo to expand in areas of shared priorities and work together with like-minded states.

As for issues of substance such as security, semiconductor firewalls, trade and coordinated diplomacy, all are pragmatic and achievable platforms for cooperation. Opportunities for increased collaboration in areas such as renewable energy, where both Japan and South Korea are investing heavily, are also present. By working together, they could share expertise, resources and accelerate the development of new technologies and infrastructure.

Friends and allies of Japan and South Korea want them to be successful. On Yoon’s visit to Washington to announce the Washington Declaration, U.S. President Joe Biden explicitly praised Yoon for his political courage and personal commitment to diplomacy with Japan.

Other capitals from Ottawa to Canberra, Berlin to New Delhi also view the rapprochement to be one important enough to support and are publicly praising the high-level leadership engagement and willingness to re-engage.

Canada, in its new Indo-Pacific Strategy, explicitly highlights the importance of both Japan and South Korea in their strategic engagement and are opening new opportunities for security cooperation, including through the negotiation of a General Security of Information Agreement with Japan and, in the future, with the Republic of Korea.

European observers such as Alexander Lipke and Elli-Katherina Pohlkamp of the European Council on Foreign Relations argue that European countries should encourage initiatives to integrate Japan and South Korea into structures through which they can jointly assume responsibility for the region. They cited, for example, the addition of South Korea to the Quad and noted such long-term collaboration with other partners could help limit drastic policy reversals following changes in government.

Yoon’s leadership on resetting the relationship with Japan has not translated into popular political support at home yet. Many South Koreans still think Japan needs to do more in regard to historical issues. In Japan as well, apology fatigue is palpable with many feeling South Korea continues to change the apology goal line making resolution no longer possible.

Both leaders will need to be sensitive to these populist views in their home countries and find ways to build pragmatic, visible and tangible avenues of cooperation that demonstrate to citizens in their respective countries that future oriented cooperation can take place while they find creative ways to not forget the past.

Dr. Stephen Nagy is a professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo, a fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute; a senior fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute; a senior fellow at the East Asia Security Center; and a visiting fellow with the Japan Institute for International Affairs.