By Heather Exner-Pirot and John Desjarlais

By Heather Exner-Pirot and John Desjarlais

September 1, 2022

Introduction

In recent years, Indigenous communities have had their rights used to advance agendas related to resource development, both for and against. Rather than nations being able to determine for themselves, through their own informed deliberations, under what circumstances they will engage in resource development, external influences have often sought to shape Indigenous decision-making. More often than not, this has been directed at rejecting participation in projects altogether, due to their environmental impacts. Many journalists, activists and political leaders have turned this into a trope: that because Indigenous people are caretakers and stewards of the land, their natural position must be to stop resource development and be a last line of defence for protecting the earth.

This has had severe consequences on the economic prospects of First Nation, Inuit and Métis peoples. All nations must find ways to achieve sustainable development, and modern lifestyles depend on resource extraction. Almost every First Nation, Métis or Inuit community is engaged in resource development in some capacity, from oil and gas to mining, and from forestry to commercial fishing; and certainly every Indigenous community uses products from those activities to meet their basic material needs. And yet there has often been pressure to reject the benefits that arise from such development, even as it comes from their own territories. This despite the fact that Indigenous peoples have amongst the poorest socio-economic outcomes in Canada and are working to reduce their forced dependency on the federal government and regain the capacity to be self-determining.

For many, the media coverage of the Wet’suwet’en conflict over the Coastal GasLink pipeline epitomized the caricature of all Indigenous peoples being opposed to natural resource development. Those in favour – including the elected leadership of the 20 nations along the pipeline route, who had conducted their own engagement and consultation with their communities over several years – were routinely dismissed or ignored. Very little nuance of what was, and remains, a complex situation was presented, and outside political pressures effectively overwhelmed and displaced community processes for decision-making.

Believing through their own anecdotal experiences that the majority of Indigenous peoples support resource development where it provides social and economic benefits to their communities while mitigating environmental impacts, the Indigenous Resource Network sought to provide objective evidence of Indigenous people’s attitudes towards natural resource development. The Indigenous Resource Network is an independent, non-partisan, Indigenous-led organization with a mandate to advance the interests and perspectives of Indigenous resource businesses and workers.

This commentary is a result of that effort and describes the findings of two surveys, conducted by a reputable third-party (Environics Research) in each of 2021 and 2022, that polled Indigenous people about natural resource development. While support was not universal, nor unconditional, the surveys confirmed that a majority (65 percent) of Indigenous people across Canada do support resource development, and that their support can be enhanced through environmentally and socially responsible practices.

Polling Indigenous people

The polling firm Environics Research was commissioned for the surveys based on previous work they had conducted with Indigenous peoples, including with APTN (Aboriginal Peoples Television Network). There have been few opinion surveys of Indigenous people in Canada, despite what may be assumed to be strong public interest in their positions on various issues. At least part of the reason for this lack of data is that it is not easy to get representative samples. First Nation, Inuit and Métis peoples represent approximately 4.9 percent of the population of Canada. The current standard for sampling is random telephone calling. As such, pollsters have to call 20 times as many phone numbers for an Indigenous-specific sample than for a typical Canadian sample. This greatly increases the time and cost to conduct such surveys.

To mitigate these challenges, it was decided to concentrate polling in geographic areas with significant Indigenous populations. In practice, this meant excluding large urban centres and focusing on rural areas. Because the survey was meant to gauge Indigenous attitudes towards resource development, this was deemed an appropriate compromise, as those living in rural areas and on reserve are much more likely to be impacted by such activities.

Methodology

Two surveys were conducted by Environics, one in March-April 2021 and the second in January-February 2022. The same questions and wording were used wherever possible, although some additional questions focused on forestry were added for the latter (see Appendix I for the questions from the second survey). Natural resource development was defined as oil and gas, mining, commercial fisheries and forestry. In the first survey, all provinces and territories were included. In the second, areas without commercial forestry, including Prince Edward Island and all three territories, were excluded.

The first survey was based on telephone interviews conducted with 549 self-identified First Nations, Inuit or Métis adults living in a rural area (56 percent) or on a reserve (44 percent), and the second with 510 respondents with the same on-off reserve split. The margin of sampling error was virtually identical: for a sample of 549 non-urban Indigenous people it was +/- 4.2 percent, 19 times in 20; and for 510 it was 4.3 percent. The results for the same questions on both surveys were all within the sampling error margin, indicating that they were not outliers. Indeed, the survey results were replicated. Results from both are presented below; 2021 results are generally selected as they include results from all across Canada, though results specific to forestry are selected from the 2022 survey.

Results

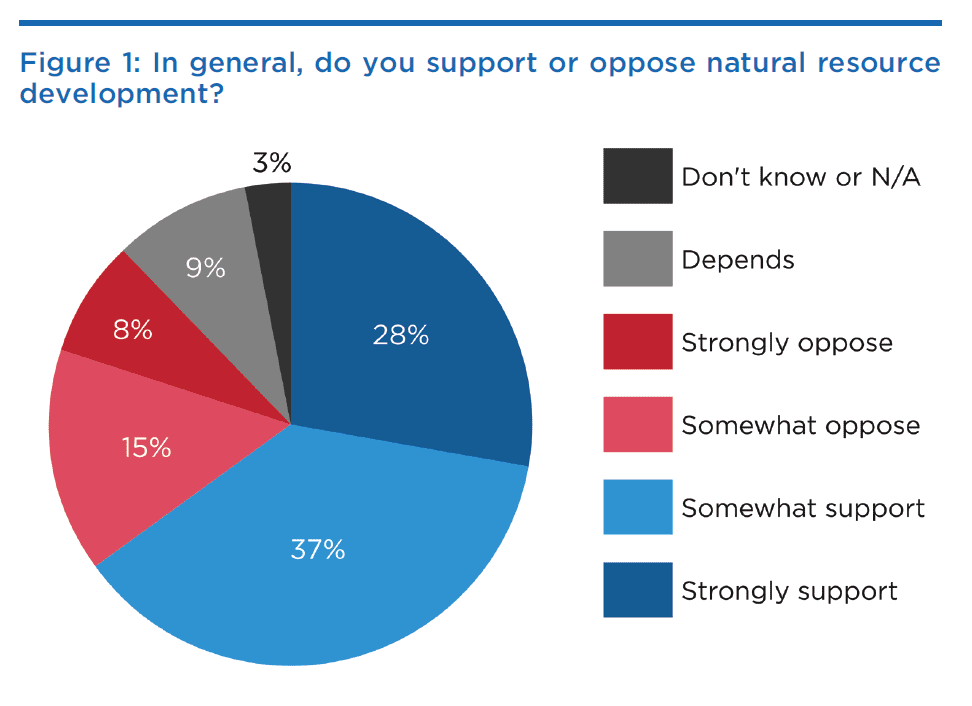

The main hypothesis – that despite how media and many politicians often portray Indigenous peoples, the majority of them do indeed support resource development – was confirmed in the survey results. When asked if they support or oppose natural resource development, 65 percent of respondents indicated they support or strongly supported it, and 23 percent said they oppose or strongly oppose it. Another 9 percent said it depends, and 3 percent said they didn’t know (Figure 1).

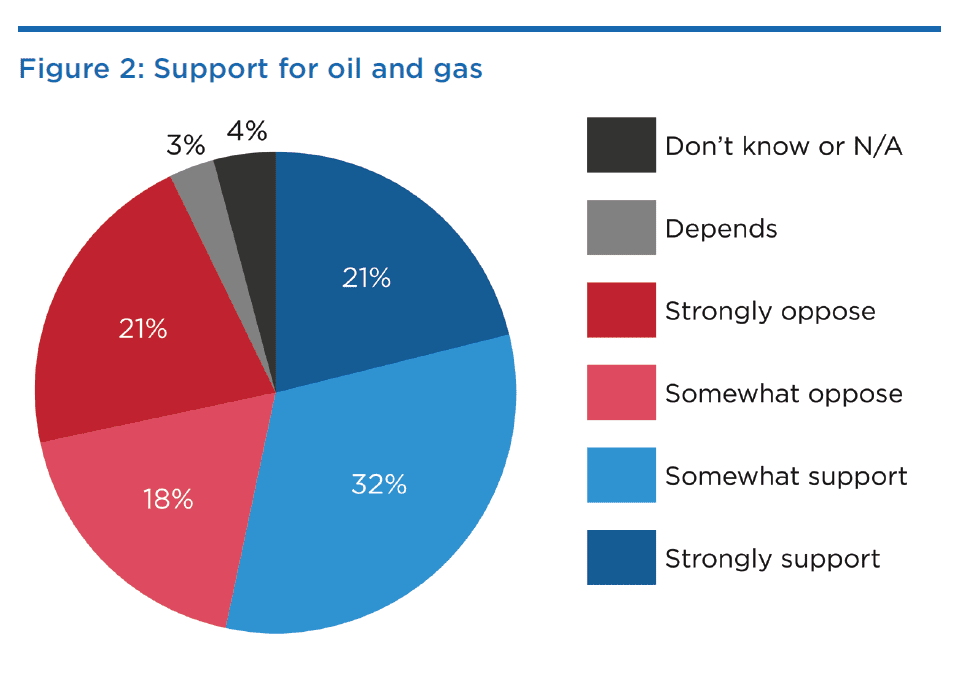

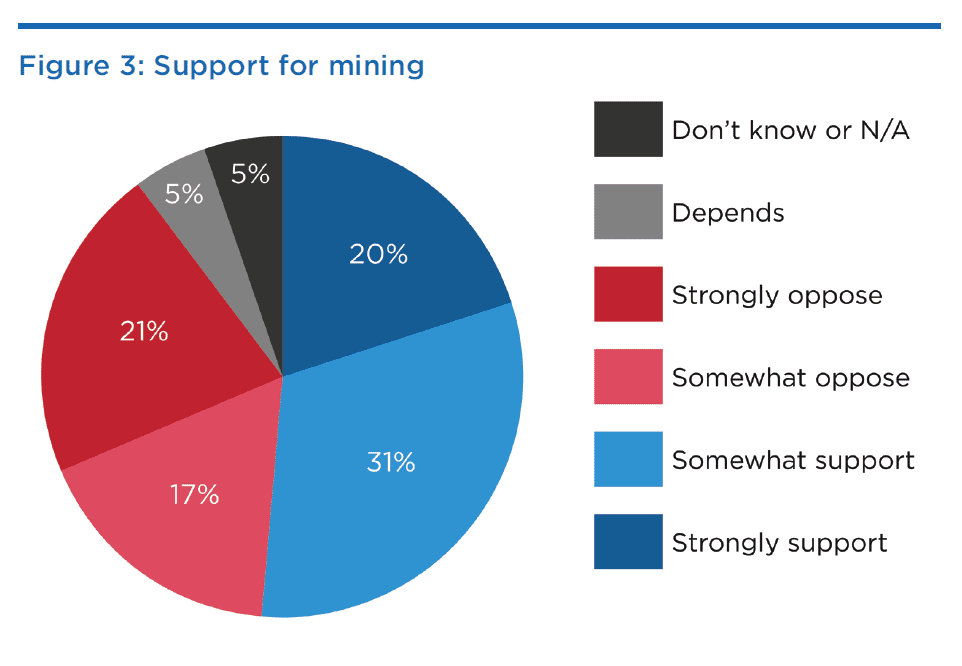

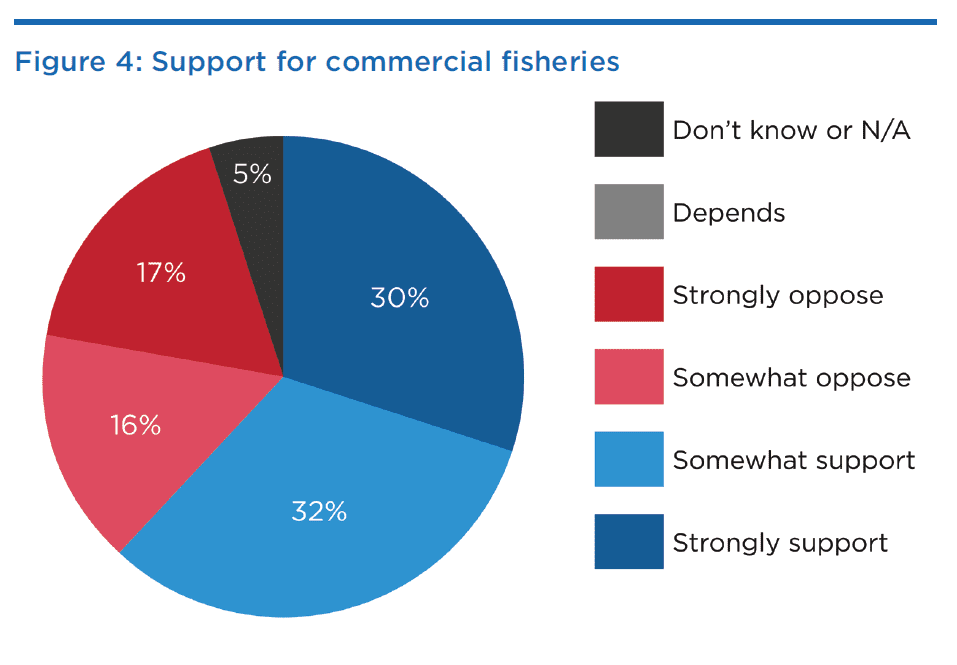

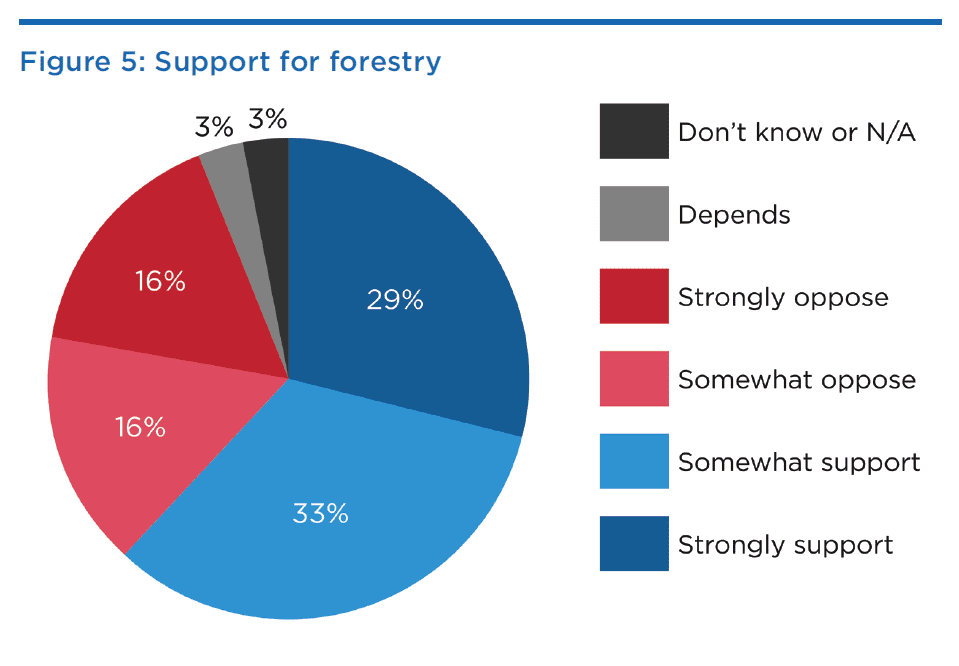

Respondents were also asked about specific sectors, including oil and gas, mining, commercial fisheries and forestry.

Not surprisingly, forestry and commercial fisheries had higher support than oil and gas, and mining. Indigenous peoples have always used the forest, oceans, lakes and rivers to sustain themselves physically and spiritually, and have direct experience with their management, which can be done at smaller scales. Mining and oil and gas are non-renewable activities, without historical Indigenous precedence, and require significant capital and industry involvement.

Nonetheless, majorities of Indigenous people supported all four sectors.

Support was at the upper end of the spectrum for forestry (62 percent support, 29 percent strongly) and commercial fisheries (62 percent support, 30 percent strongly). The level of support softened with oil and gas (53 percent support, 21 percent strongly) and mining (51 percent support, 20 percent strongly) projects (see Figures 2-5). However, support still outweighed opposition by a significant factor.

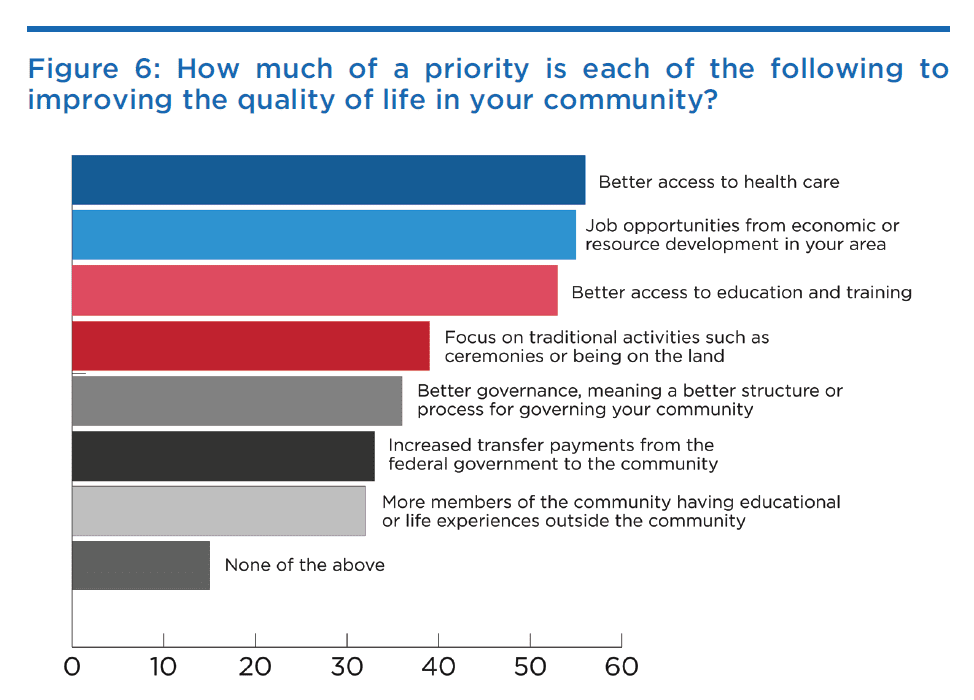

The reasons for the support for natural resource development can be linked to the importance that resource development has for jobs in rural and reserve areas. Respondents placed the creation of job opportunities from economic or resource development in the area (55 percent) within the top three urgent priorities for improving quality of life in their communities. This was on par with better access to health care (56 percent) and better access to education and training (53 percent) (Figure 6).

Interestingly, support was slightly higher for resource development in the abstract than for actual projects. For those respondents that indicated there were actual resource projects taking place in or near their community, 59 percent supported it compared to 39 percent that opposed it. Support was also more conditional for projects proposed in or near respondents’ community. While 54 percent said they would support such a project, a significant proportion (17 percent) said it would depend.

Factors that improve acceptance

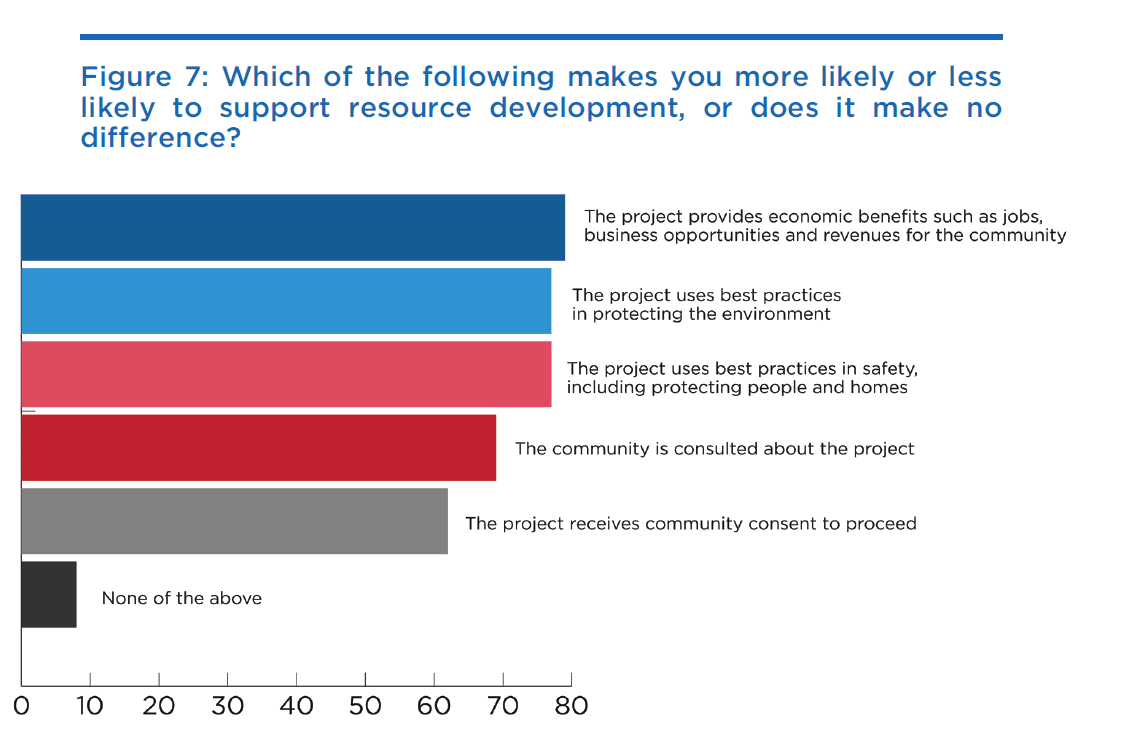

It is understood that most Indigenous peoples and communities are not universally opposed to natural resource development, but rather reserve their support for those projects that align with their values. In order to gauge which characteristics of natural resource development were most important to securing their support, respondents were asked whether the following features made them more or less likely to support an activity (Figure 7).

Best practices in protecting the environment were the most important factor, whereas community consent was the least. This is somewhat counterintuitive, as consent is a very common discussion point in legal and rights-based narratives. It may be grounded in the distrust some Indigenous peoples have in their governing institutions. However, there were no follow-up questions in the poll itself to determine such motivations.

In addition, the more informed a respondent felt about the topic of natural resource development, the more likely he or she was to support it. Overall, 30 percent of respondents felt very or well-informed, 38 percent felt somewhat informed, and 30 percent felt not very or not at all informed. Among those that felt well-informed, 75 percent supported resource development, versus only 54 percent support from those who felt not informed. This indicates that more education and awareness about resource development practices and impacts would positively affect support.

Respecting the land

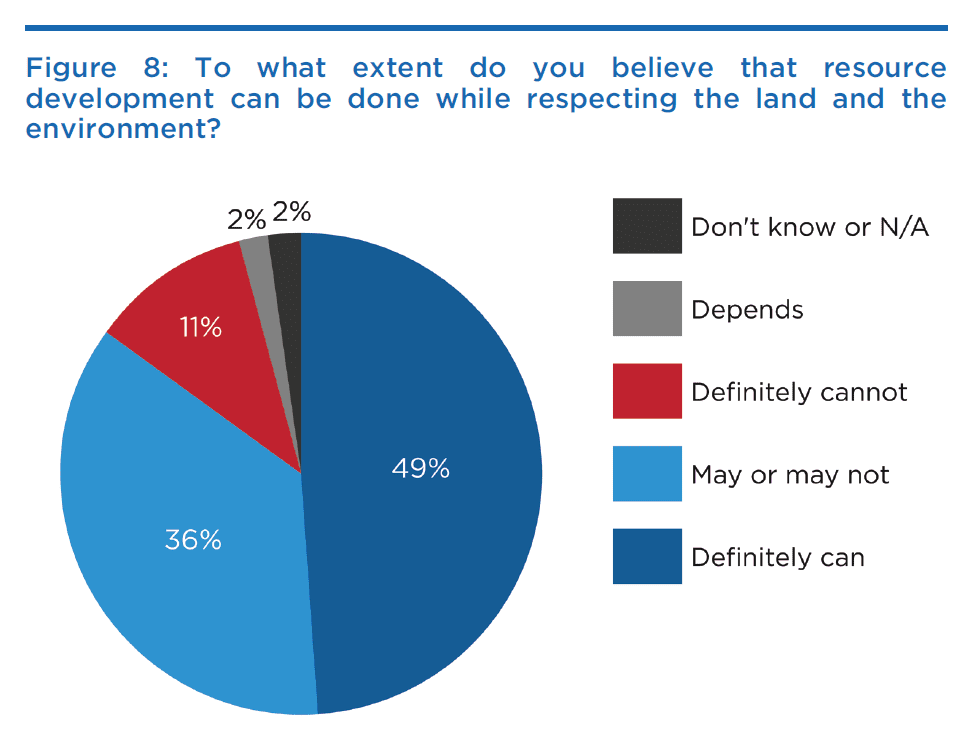

Given the importance of environmental protection to Indigenous peoples and their worldviews, the survey sought to determine whether respondents thought resource development could be done while respecting the land and environment. Half thought it could, while only 11 percent thought that it definitely could not (Figure 8).

Forestry

In addition to replicating most of the 2021 survey to test its robustness, the 2022 survey added questions about forestry. About 70 percent of Indigenous communities in Canada are located in forested areas, and they have relied on the forest for food, medicine, cultural practices and their economic prosperity for millennia. As Indigenous peoples reclaim management over forestry in ever larger areas, and as the controversy over old growth logging in BC coupled with a spike in lumber prices directed more attention to Indigenous-led forestry, a survey dedicated to the topic was deemed necessary.

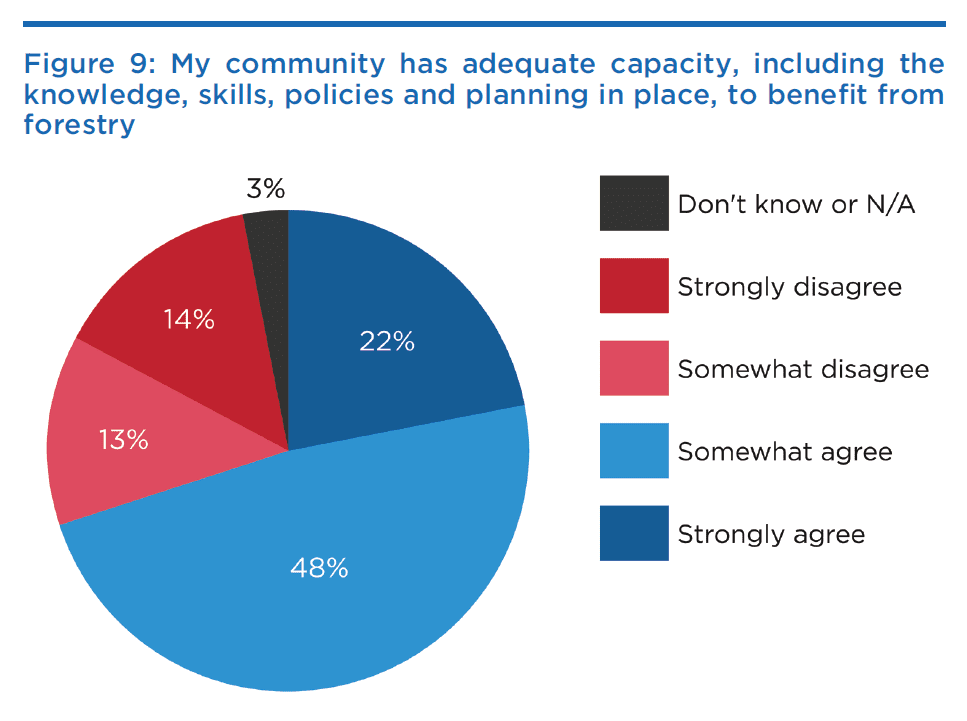

Likely owing to the deep expertise, symbiosis and historical management of forest resources by Indigenous communities, respondents were very confident in the ability of their communities to benefit from forestry.

Respondents were also asked about various forestry activities (Figure 9). Over half of respondents (58 percent) knew of a current forestry project proposed or underway in or near their community. Among this group, majorities said the project involved harvesting (75 percent), hauling (71 percent), manual or mechanical stand tending with brush cutter (68 percent), tree planting (62 percent), and site preparation (57 percent), while relatively few were aware of chemical stand tending with herbicide application (24 percent). This was asked in particular because a lot of opposition or concern with forestry projects has been in regards to herbicide application. However, it seems to not be an issue of which the average Indigenous resident is aware.

Respondents were more optimistic about the ability to conduct forestry activities sustainably than with natural resource development generally, as polled in the 2021 survey. A little over half (54 percent) believed forestry can definitely be done while respecting the land and the environment, while one-in-five (18 percent) believed it was definitely not possible to achieve both: a ratio of 3:1. Another quarter (25 percent) were more circumspect, saying it may or may not be possible.

Geographic, gender and age differences

In general, those living in rural areas were more supportive and optimistic about resource development than those living on reserve; older (> 35 years) respondents were more supportive than younger (18-34 years) ones; and Métis were more supportive than First Nations. For instance, three-quarters of rural residents (75 percent) said they supported resource development in general, compared to just half (50 percent) of reserve residents. (The number of Inuit polled was not sufficient to comprise a representative sample.)

While there were some gender differences, with men slightly more likely to support resource development across the categories of questions, they were not stark. With regards to support for natural resource development, for example, 65 percent of men and 61 percent of females supported it, a difference that lied within the margin of error.

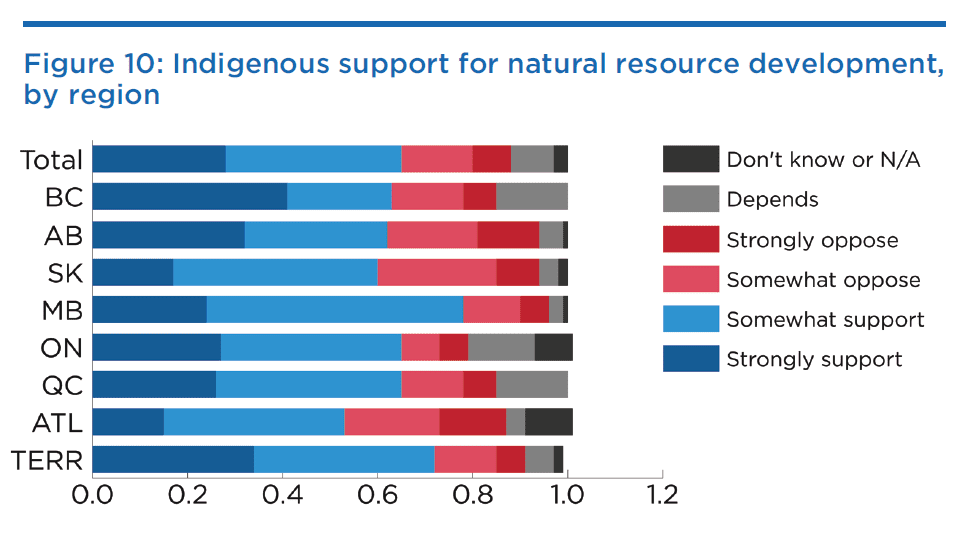

Figure 10 shows support for natural resource development amongst Indigenous respondents by province/region/territory. The sample sizes at the geographic level are too small to be considered statistically significant. As such, these results are shown only for informational purposes. The highest support was in Manitoba and the territories. The lowest support was in Saskatchewan and Atlantic Canada.

Conclusions

Despite its essential role in our lives and our economy, natural resource development has become a very polarized topic in Canada. While Indigenous opposition to resource projects has been highlighted and even celebrated in the media, the issue is not as divisive in real life as may be assumed. A significant majority (65 percent) of Indigenous people living in rural Canada support natural resource development, outweighing those opposed by a ratio of 2:1.

These results are not intended to indicate or suggest that Indigenous support for resource projects in their territories in unconditional. Rather it is meant to provide objective evidence, in what is usually a topic rife with personal bias, that First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities are open to participating in and granting consent to resource development in their territories. Hopefully these survey results encourage more Indigenous and industry partners to work together to develop projects in a good way.

About the authors

Heather Exner-Pirot has fifteen years of experience in Indigenous and northern economic development, governance, health, and post-secondary education. She is currently a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. She also serves as a research advisor part-time for the Indigenous Resource Network. She has published and/or presented on Aboriginal Economic Development Corporations, urban reserves, telehealth, Indigenous workforce development, First Nations taxation and own source revenues, distributed & distance education, Indigenous health care, Arctic human security, regional Arctic governance, Indigenous engagement in the Arctic Council, and Arctic innovation.

Exner-Pirot obtained a PhD in Political Science from the University of Calgary in 2011 and has held several positions at the International Centre for Northern Governance and Development, the University of Saskatchewan College of Nursing and its distributed sites in northern and rural Saskatchewan, and the University of the Arctic Undergraduate Studies Office. She currently works on strategy and research for pro-development Indigenous groups in Western Canada, and consults directly for First Nations and Métis clients through Morris Interactive. Exner-Pirot is also a Research Associate at L’observatoire de la politique et la sécurité de l’Arctique (OPSA) at the Centre interuniversitaire de recherche sur les relations internationales du Canada et du Québec (CIRRICQ).

John Desjarlais Jr. is Nehinaw (Cree)-Métis from Kaministikominahikoskak (Cumberland House), Saskatchewan with proud ties in Treaty 4. John started his career in 2001 in the mining industry and worked in a variety of roles including environment and safety, maintenance, and reliability engineering management. During this time, he also completed an undergrad in Mechanical Engineering, and a Master’s in Business Administration. John now proudly serves as the General Manager of Great Plains Contracting, an Industrial construction company whose primary owner is FHQ Developments. John proudly makes time for community and serves as the Chair of the Indigenous Resource Network, President of his engineering and geoscience regulator (APEGS), and as Director/Chair in areas of Safety (Saskatchewan Construction Safety Association), Indigenous outreach/development/and engagement (CIAC-AISES, IRN) and Post-Secondary (Sask Poly). John is also in the home stretch to complete his master’s in Governance and Entrepreneurship in Northern and Indigenous Areas (GENI) through the University of Saskatchewan.