This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Shuvaloy Majumdar, March 18, 2022

In the contest of empire versus Pax Americana, all our postwar arrangements are now apocalyptically afire. Seventy-five years into the postwar world, two of five of the permanent United Nations Security Council members charged with the responsibility of ensuring international security are shredding apart all treaties and norms, while the other three are discordant, presiding over deeply divided societies.

Russia and China have been afforded the West’s best intentions. The G7 expanded to include Russia, creating the G8, and NATO established confidence measures and the NATO-Russia Council. China was granted “most favoured nation trading status,” a seat at the World Trade Organization and prominence in multilateral organizations. None of this was earned; neither Russia nor China divested their military ambitions, dispensed with their revanchism or displaced arbitrary authoritarian rule with democracy and open markets.

As their decisions to decouple from the international system compounded, as they pursued dreams of “dual circulation” to export boldly while curtailing access to domestic markets, as the state-capitalist Belt and Road initiative challenged democratic capitalism, democracies grew more complacent and prone to elite capture and corruption.

The West’s nihilistic obsession with post-modernism swelled, imbued with performative stances on issues ranging from human dignity to energy security, and an incapacity to define and confront the threat of a rising illiberal age. Now upon us, the threat of empire violates Euro-Atlantic borders materially and democratic freedoms morally.

Time will tell just how much of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was predicated on an assumption of western weakness. What can now be said is that no concession can be afforded to Vladimir Putin. The only victory to be had is one that fully affirms Ukrainian sovereign decisions over its Euro-Atlantic future and completely repudiates authoritarian ambitions to carve new borders from the rubble of decimated cities and destroyed lives.

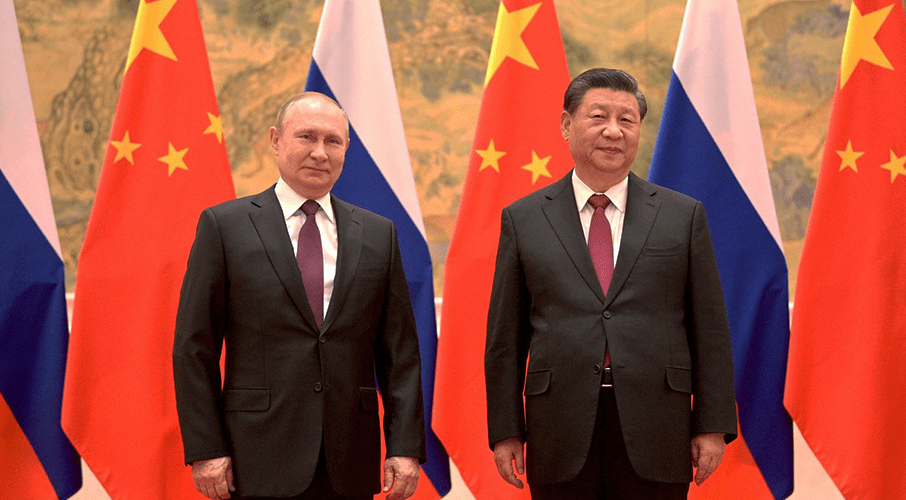

Days before Putin ordered his military to invade, he stood alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping, flanked by Olympic regalia and awash with the boundless ambition for the empires they seek to restore. The two lifetime rulers — undeterred by well-intentioned protestations, unbowed by democratic resolve — stood undeterred in a shared vision of their own dominance over their neighbours and the world.

From their vantage, at every turn over the last decade, the democratic world adhered to a pattern of half-measures to conciliate, failing to make the hard decisions that would defend the rules-based international order against their authoritarian ambitions.

In Venezuela, an unchallenged authoritarian consolidation. In Crimea and Donbas, a policy of strategic management. Between Syrian President Bashar Assad and ISIL, containment. In Hong Kong and Xinjiang, performative theatre. Tehran, entreaties; Kabul, retreat.

The democratic world’s aversion to confronting authoritarians for what they are, instead longing for a return to an elusive “normal” they wished they had, can be summed in one word: appeasement.

The leaders of the world’s democracies must define together the scale of the threat our rivals pose, and decide on a plan for their defeat. This is not just a war of the reunification of the Russian Empire under the shadow of Putin’s nuclear umbrella; it is also one that is waged economically and asymmetrically, backed by Xi Jinping’s Middle Kingdom. Whatever the outcomes of Putin’s miscalculations in Ukraine, Xi emerges with greater strength.

Until we confront this illiberal project posed by medieval rivals to the modern age of democracies, the threat will loom larger, not smaller. The task will grow more difficult, not simpler.

It will require some difficult realizations, starting with the fact that securing NATO’s borders means securing Ukraine’s, not negotiating them with an invading force. It also means realizing that the geography of this challenge extends beyond the Euro-Atlantic to the Indo-Pacific.

The challenge must be considered in light of new concessions being deliberated with an Iranian regime that launches strikes across the Persian Gulf and into Iraq, as well as the land and maritime borders that the People’s Liberation Army is challenging from the Taiwan Strait to the Himalayas.

Beijing views Russia as a gas station, a farm, a security contractor, some rocks and a pliant UN Security Council proxy with diminished economic influence. In response to western sanctions, the People’s Republic of China has locked in discounted long-term Russian oil and relaxed wheat imports.

It benefits from the adventures that Russian mercenaries undertake in Africa, and has secured Russian metals for its international electrification schemes. It has deployed Huawei to strengthen Russia’s surveillance state, and co-ordinated diplomacy against America in Iranian nuclear negotiations, where it holds a $400-billion Belt and Road economic interest.

In international organizations, it occupies strategic positions to hasten the displacement of the international order with one that is Beijing-centric. The PRC has taken up Putin’s “denazification” propaganda, while creating symbolic distance and deniability. Whatever Putin’s fate, Xi Jinping knows that Beijing wins. If Putin is successful in Ukraine, western weakness is laid bare. If he fails, Xi carves his interests out from the Russian collapse.

China’s weaponized commerce, its data colonialization and natural resource hegemony demand that democracies take on the task of decoupling from the risks of its strategic exploitation. Today’s proxy war being waged on Ukrainian soil isn’t just about European borders. It is about the terms of a larger contest that’s already underway.

We have arrived in a world where stronger tools are needed: imposing economic blockades against supply chains that fortify the Kremlin’s war machine, deploying secondary sanctions against PRC entities poised to supplant Russian industries and readying emerging and established alliances, from the capabilities of the Quad to NATO, to defend against the concept of a two-front war.

The time has come to reclaim and renew the doctrine of peace through strength. It is time to dispense with the frailties that democracies have found themselves obsessed with. Our town squares are burning. Mobs of collectivist narcissists threaten individual dignity and freedom, trafficking in identities over ideas. The time has arrived for the return of leaders with conviction — leaders who do not bow before the illiberal age upon us, but who instead unlock the economic and military strength required in this generation’s greatest test.

We need not look to 1945 or 1989 to see how this story will unfold. We need not experiment with various versions of appeasement, thus prolonging a decision to rise to the moment before us. History has recorded the resiliency of democracies, and of the violent collapse of unchecked authoritarians under the yoke of their states.

In this, Vladimir Putin has crossed all the lines. It is why he cannot be allowed to succeed. It is why the aspirations of the Ukrainian people to choose to join the European Union and NATO cannot be surrendered to Kremlin domination. It is why not an inch of Ukrainian territorial sovereignty can be ceded — not Donbas, not Crimea, not any of the territories being terrorized today by Russian forces.

Putin no longer holds the capacity to achieve his designs, having replaced the promise of perestroika and glasnost with the madness of imperiya, which is why this has to end with the end of his tyranny.

Shuvaloy Majumdar is Foreign Policy Program director and Munk senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and former director of policy to Canadian foreign ministers.