The Canadian government falls short of its international legal obligations and fails to acknowledge an ongoing genocide, writes Gary Caroline.

The Canadian government falls short of its international legal obligations and fails to acknowledge an ongoing genocide, writes Gary Caroline.

By Gary Caroline, March 1, 2021

On January 12, 2021, then Minister of Foreign Affairs François-Philippe Champagne and Minister of Small Business, Export Promotion, and International Trade Mary Ng announced certain measures in response to the oppression of the Uyghur community in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

The Global Affairs news release described Canada’s position as follows:

Canada is gravely concerned with evidence and reports of human rights violations in the People’s Republic of China involving members of the Uyghur ethnic minority and other minorities within the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (Xinjiang), including repressive surveillance, mass arbitrary detention, torture and mistreatment, forced labour and mass transfers of forced labourers from Xinjiang to provinces across China. These activities strongly run counter to China’s international human rights obligations.

In coordination with the United Kingdom and other international partners, Canada is adopting a comprehensive approach to defending the rights of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities, including by advancing measures to address the risk of goods produced from forced labour from any country from entering Canadian and global supply chains and to protect Canadian businesses from becoming unknowingly complicit.

The news release states that Canada would be taking several steps in this respect: the prohibition of imports of goods produced wholly or in part by forced labour; a Xinjiang Integrity Declaration for Canadian companies; a business advisory on Xinjiang-related entities; enhanced advice to Canadian businesses; export controls; increasing awareness for responsible business conduct linked to Xinjiang; and a study on forced labour and supply chain risks. In reality, however, nothing either new or meaningful can be seen in these proposed actions.

This weak response by the Canadian government is in sharp contrast with the strong stand taken by the United States, including multifaceted legislation (Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020), sanctions, and the US State Department declaration, issued on January 17, 2021, that the Chinese government’s conduct in respect of the Uyghurs constitute a genocide and crimes against humanity.

Canada is a signatory to the Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, 1930. As such, the government is required to “sanction the perpetrators of forced or compulsory labour.” Clearly, the Chinese authorities are using forced labour in Xinjiang as an important instrument in their campaign to destroy the Uyghurs as a distinct people. Yet the recent announcement by the Canadian government to address the oppression of the Uyghur community in Xinjiang offers little in terms of immediate meaningful impact on companies operating in Xinjiang. We address why companies operating in the region should still be concerned.

The prohibition of imports of goods produced wholly or in part by forced labour

The government’s own Backgrounder states that the impetus for this welcome step in the fight against forced labour was the obligation contained in the revised Canada, United States, Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), which requires the three Parties to codify the prohibition through domestic legislation. As the government describes it, “This legislation provides a basis for enforcement against goods produced by forced labour originating in or transferred from Xinjiang.”

Yet this measure was not in response to the situation in Xinjiang. One might ask why Canada says that it moved to adopt these albeit tepid measures to ensure compliance with CUSMA when it was already obligated by the international conventions it has signed to make forced or compulsory labour punishable in Canadian law and to “adequately and strictly” enforce it.

A Xinjiang Integrity Declaration for Canadian companies

This “measure” relies on companies to self-report by signing a declaration that they are “aware of the human rights situation in Xinjiang,” will respect Canadian and international laws and OECD and UN guidelines, and “affirm that they are not knowingly sourcing products or services from a supplier implicated in forced labour or other human rights violations.” Moreover, the penalty for failing to report is toothless – the withdrawal of trade advocacy by the Canadian government. This is the same milquetoast approach and structure as used with the government’s Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise.

A business advisory on Xinjiang-related entities

Another government measure has been to issue “business advisories” which caution companies sourcing products in Xinjiang. That is certainly advisable but it’s hardly a “measure” in the fight against forced labour.

Enhanced advice to Canadian businesses

The same can be said for this – repetitive – point regarding “enhanced advice on due diligence and risk mitigation related to supply chains and forced labour.”

Export controls

It is welcome that Canada will deny export permits to Canadian companies supplying technology and services that could be used for “government surveillance, repression, arbitrary detention or forced labour” in China’s surveillance state in Xinjiang. But Canada should adopt a more aggressive stance by giving immediate consideration to employing Magnitsky and other sanctions on the leadership of Chinese or other companies deploying such technology throughout Xinjiang. Given the notorious use of this technology, there should be no hesitation on Canada’s part in punishing foreign and domestic participants in what Canada’s Parliament has declared to be a genocide.

Increasing awareness for responsible business conduct linked to Xinjiang

The government plans on convening discussions with businesses and other groups to “raise awareness about the risks of doing business in Xinjiang.” This is good, but again, tough penalties must be employed against any company violating clear prohibitions. Canada has neither clear legal prohibitions nor stiff penalties for companies sourcing, importing or manufacturing product made by forced or compulsory labour.

A study on forced labour and supply chain risks

It is astounding that Canada (Global Affairs) lacks the internal capacity to analyze “areas of exposure to forced labour involving Uyghurs.” Further, it would help Uyghurs much more if Canada contributed to the body of legal measures punishing the architects of forced labour in Xinjiang.

The risk to companies operating in Xinjiang

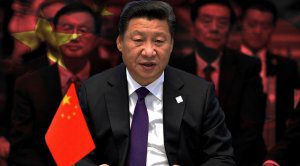

Sourcing, selling or operating in Xinjiang may be appealing to some companies which prize stability more than their responsibility to act ethically in conducting their affairs. Xinjiang is a “secure business environment” only until the light of human rights shines on what the Xi Jinping regime is doing to the Uyghur people.

The risks associated with ignoring what is going on there are great.

- Penalties for ignoring legislation prohibiting doing business in Xinjiang;

- class actions by Uyghurs and others working in the company’s supply chain; and

- shareholders and consumers challenging your decision to do business there.

Gone are the days when companies could operate where they wanted, in the manner of their choosing without bearing the consequences of their reckless behaviour.

Conclusion

While Canada’s hesitancy in confronting the many challenges posed by China may be somewhat understandable in responding to the incarceration of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, there shouldn’t be any quandary for the government when determining how it will respond to a genocide in the making. A nation’s moral principles must guide its response. Silence or tepid measures will accomplish nothing more than providing the basis for saying “we’re doing something.”

Canada knows that China’s goal is to eliminate the Uyghurs as a distinct people. For a government that believes in human rights for all, what it has or hasn’t done in respect of the Uyghurs is on both counts unacceptable.

There is no better, more urgent time than now for countries like Canada to enact comprehensive legislation against forced labour. It would have the immediate effect of communicating our solidarity with the Uyghurs of China and signal Canada’s recognition of the gross human rights violations being perpetrated by the Xi Jinping regime.

Based on legislation enacted by other countries such as Australia (in 2018) and the United Kingdom (in 2015), a Modern Slavery Act would demonstrate Canada’s resolve by imposing strict reporting requirements on all companies working in or importing product from China. The failure to report should result in stiff penalties aimed at ensuring compliance and not simply the loss of trade advice from the Canadian government.

The universal fight against forced or compulsory labour through potent measures aimed at combatting it, must be complemented by national initiatives to mount global pressure on the Chinese authorities to end their oppression of the Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in Xinjiang.

The United States’ Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020 provides an important precedent that Canada and other countries should follow – in particular, the imposition of sanctions against the Chinese officials primarily responsible for its actions as well as any company directly or indirectly engaged in the oppression of the Uyghur people.

Finally, and urgently, the Canadian government on its own or in conjunction with others must adopt strong measures aimed at convincing the Chinese government to end the genocide of the Uyghur and other Turkic people and punish any company doing business in or with Xinjiang. Where the origin of the product is unclear, Canada should simply ban the product from being imported.

Canada’s Parliament has spoken. The measures we suggest are among those that the Canadian government should adopt as a first step in what will likely be a long campaign to end the destruction of the Uyghurs. Let Canada live up to the clarion call of the very first Article of the Genocide Convention.

The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.

Gary Caroline is an international lawyer and the President of The Ofelas Group Inc. Follow him on Twitter: @Gary_Caroline