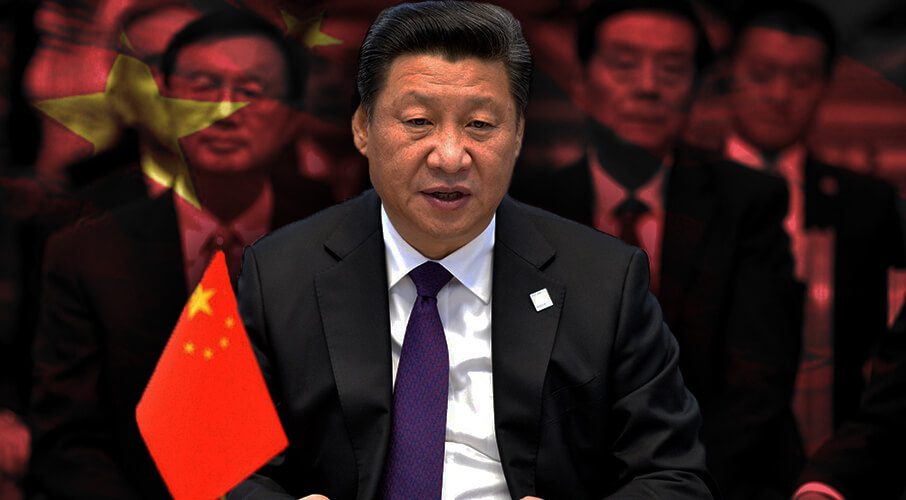

China attempts economic coercion all the time, and countries should be less intimidated by it than they often are, writes Duanjie Chen. This brief originally appeared in the Ambassador’s Brief.

China attempts economic coercion all the time, and countries should be less intimidated by it than they often are, writes Duanjie Chen. This brief originally appeared in the Ambassador’s Brief.

By Duanjie Chen, October 16, 2019

My new report, Countering China’s Economic Coercion, makes a study of China’s weaponization of trade flows. It looks at why it happens, how it happens, and what countries can do about it.

In a nutshell, China attempts economic coercion all the time, and countries should be less intimidated by it than they often are: there are now plenty of case studies of countries successfully standing up to China in smart ways.

Here, I unpack four lessons from the report, and their implications for policy makers:

1. China attempts economic coercion often and for a wide variety of reasons

China often attempts economic coercion if it perceives a challenge to its:

- Territorial integrity and sovereignty: e.g. in 2012, China instituted a sudden ban on imports of Filipino bananas, as a result of its Scarborough Shoal dispute with the Philippines in the South China Sea.

- Regime legitimacy: e.g. in 1992, China excluded France from bidding on a subway project in China as a result of the French selling fighter jets to Taiwan.

- Chinese norms: e.g. in 2010, China targeted Norwegian salmon sold in China with “food safety regulations” after the Norwegian Nobel Committee honoured a jailed Chinese dissident with a Nobel Peace Prize.

2. Chinese economic coercion attempts are typically well calculated

Chinese economic coercion is often:

- Discreet enough to evade WTO disputes: e.g. with the Norwegian salmon dispute, China issued no formal import restrictions, rather, it conducted prolonged inspections in the name of health.

- Tailored to split western allies: China often alternates the countries which it targets, effectively pitting those countries against each other in a competition for friendlier China policies. For instance, it has rotated its targeting of France and Germany.

- Calculated for maximum impact: often, when coercing democracies, China will target constituencies which are likely to be loud and insistent on “forcing” their own governments to yield to China’s demands – e.g. farmers.

3. However, targeted countries often have more capacity to push back against China’s economic bullying than they initially perceive

The size of the Chinese market means that the threat of Chinese economic coercion often strikes fear into targeted governments.

But countries are often in a better negotiating position than they initially realise.

The current case of Canada, whose farmers are enduring several Chinese agricultural bans as a result of Canada’s arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, is instructive.

Canada has multiple potential sources of leverage against China including:

- Favourable asymmetry in the trade relationship: the majority of Canada’s exports to China are commodities for which China has to rely on global markets where Canada is a major supplier. In contrast, all Canada’s imports from China are ordinary manufactured goods that are easily replaceable from competing manufacturers in other countries.

- The ability to withdraw funding from Chinese projects: Canada could withdraw its funding from the China led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). It could even reallocate some of those funds to compensate affected farmers.

- The ability to ban / restrict Chinese companies: Canada could ban Huawei from participating in its 5G networks. It could also block Chinese funded R&D efforts in Canada – some of which are intended to steal Canadian IP.

4. There are now plenty of case studies of countries successfully standing up to China’s economic coercion

Although some countries have chosen to capitulate to, or appease China, there are a growing number which have successfully stood up to China by demonstrating resolve, and restructuring their trade flows:

- South Korea demonstrated its resolve: in 2015, Chinese consumers boycotted the South Korean Lotte Group as a result of South Korea purchasing a U.S. Missile defence system. The South Korean government refused to yield to Chinese pressure. So, Lotte Group closed and divested its Chinese retail assets.

- Japan found alternative suppliers: in 2010, China triggered an “administrative halt” on exports to Japan of a rare earth element, as a result of the Senkakku / Diaoyu Islands dispute. Japan quietly found alternative suppliers of that element.

- Taiwan has actively diversified: Taiwan, which is most vulnerable to China, has long made conscious efforts to reduce dependence on Chinese markets. Its “New Southbound Policy” subsidizes Taiwanese companies to relocate from China to other countries in the Indo-Pacific.

These lessons have implications for policy makers:

- Pre-emptively diversify trade away from China: China weaponizes its trade flows frequently enough that it is not prudent to be highly exposed to China in any one sector. This is especially so for countries with values / interests which are likely to come into conflict with China’s.

- Don’t panic if subjected to Chinese coercion: begin by making a rational assessment of the potential economic costs. And then move onto an assessment of the sources of leverage held over China. The situation is likely less dire than it initially appears.

- Learn from analogous cases: there are now plenty of successful precedents to learn from in formulating an effective response.

- Demonstrate resolve and use your leverage: countering China’s economic coercion does not mean taking a blindly confrontational approach towards China. But it does mean standing up for values and refusing to be bullied.

- Investigate opportunities for collective action: we can mitigate China’s capacity for economic coercion if like-minded countries stand together to counter it.

Duanjie Chen, an independent scholar with a PhD in economics, is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Her latest report is Countering China’s Economic Coercion.