We should ensure personal income tax rates on “super donors” are not starving them from funding, writes Sean Speer.

We should ensure personal income tax rates on “super donors” are not starving them from funding, writes Sean Speer.

By Sean Speer, July 15, 2019

A special Senate committee struck in 2018 to investigate the intersection between public policy and charitable giving released its first study to minimal fanfare last month. The report, titled “Catalyst for Change: A Roadmap to a Stronger Charitable Sector,” provides a useful primer on the current state of Canada’s charitable sector and the opportunities and challenges that it faces. But one cannot help but feel like the committee’s neglect of the role of personal income tax rates in influencing charitable giving is a major omission.

The report rightly observes that the number of charitable donors fell by 50,000 in 2017. It cites various representatives from the sector who are concerned about this “downward trend” and the consequences of sustained “underinvestment” in Canadian civil society. One witness even estimated a “social deficit” (representing the gap between charitable giving and charitable needs) of $26 billion by 2026. And, of those who responded to the committee’s survey questions, 68 percent indicated that the funding stability of their organizations was “very concerning.”

In response to these overwhelming concerns about the overall funding environment for charities, the committee considers different options to try to catalyse more charitable giving, such as increasing the generosity of the Charitable Donation Tax Credit or extending its preferential treatment to different types of assets. Ultimately it recommends that:

[T]he Government of Canada, through the Minister of Revenue and the Commissioner of the Canada Revenue Agency, direct the Advisory Committee on the Charitable Sector to review existing tax measures available to individual donors in order to strengthen the culture of giving among new and current charitable donors.

Such a review must extend beyond the design and generosity of the Charitable Donation Tax Credit and consider the role of high marginal tax rates on individuals in contributing to the decline in charitable donors in Canada.

New MLI research aims to initiate this work. Our new paper provides a primer on charitable giving in Canada and examines the scholarly literature on the relationship between personal income tax rates and charitable giving.

The latter point is key: Ottawa and several provinces have enacted a series of rate increases for high-income earners in recent years and can anticipate that the upcoming election campaign will involve the spectre of further tax hikes. Seven of ten provinces now have combined top marginal tax rates exceeding 50 percent and the others are close. It only seems prudent to attempt to understand how these tax rate increases may affect charitable giving and in turn enlarge the “social deficit” described to the Senate committee.

What does our paper find?

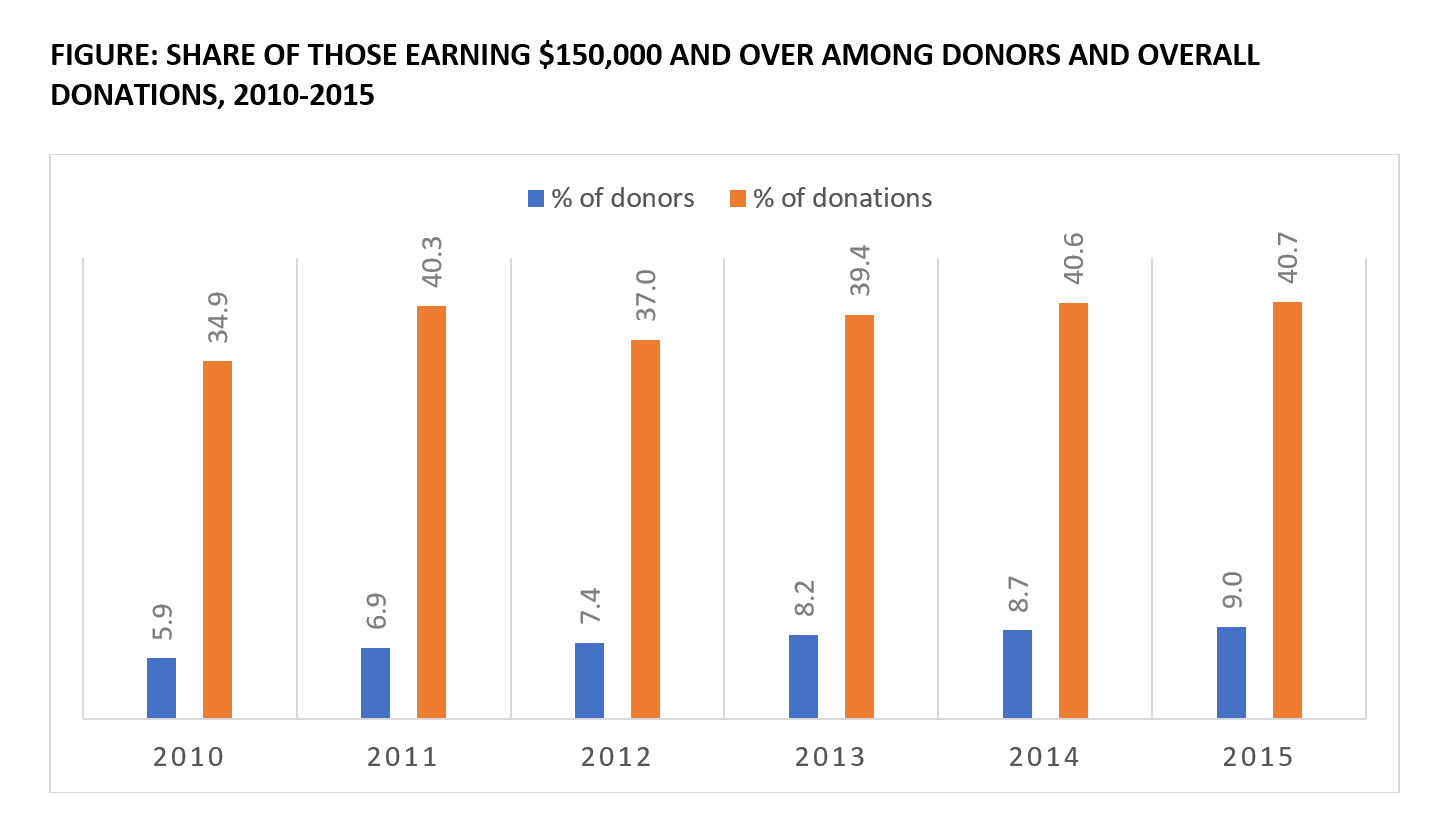

The same high-income earners who have been targeted to “do a little more” with tax rate increases are disproportionately responsible for philanthropy and charitable giving in Canada. Those earning $150,000 or more represent only 9 percent of all charitable donors but have consistently provided about 40 percent of the total value of charitable donations across the country (see figure below). These “super donors” are critical to financing the operations and activities of Canada’s charitable sector.

It only makes sense therefore that policy-makers try to understand the potential behavioural effects of rising personal income tax rates on charitable giving by this cohort. Especially since the outcome of less charitable giving will result, as one witness before the committee observed, “in longer waiting lines at food banks, longer waiting lines for health care, congestion, overstress on staff, and charities trying to do too much with too little.”

Our paper finds that the relationship between taxation and charitable giving is complex for four reasons. It is worth unpacking them for readers.

The first is that the motivations of donors are multi-faceted; they can include tax reasons, income levels, religious views, community solidarity, and so on. These various factors were on the display at the committee where some witnesses contended that tax incentives can have a statistically significant effect on giving and others argued that there was “no correlation between tax credits and giving levels across Canada.” The point is trying to discern what informs and shapes charitable giving is messy and not prone to simple answers.

The second is that there is a scholarly debate about whether charitable giving is more influenced by after-tax income (what is known as the “income effect)” or the interaction between one’s marginal tax rates and tax preferences for charitable giving (known as the “price effect”). Think about charitable giving just like the purchase of another commodity. Contributions are determined by a combination of how much we earn and how costly it is to give. Basically, the debate comes down to whether people give more if it is cheaper to donate or when they have more disposable income.

The third is that the relative role of “income” and price” differs among donor and income groups. Research seems to indicate that “super donors” are more responsive to changes in after-tax income than to marginal price of charitable giving. This is highly relevant for our purposes given that “super donors” play a disproportionate role in charitable giving in Canada and are the ones who have been targeted with a series of rate hikes.

The final is that evolving research methodologies and data sources are producing new and dynamic results about how donors respond to price and income changes including difference behavioural responses to transient and long-term changes. There have also been attempts to understand the interrelationship between tax policy, macroeconomic conditions, and charitable giving in the context of the 1980s personal income tax reductions in the United States. The point is that this is a dynamic area of economic research that is becoming more and more sophisticated.

What is the upshot?

Our analysis finds that, on balance, the research seems to point to the “price effect” being more significant than the “income effect” in charitable giving overall but that tax-induced changes to disposable income can also affect giving – particularly for “super donors.” It seems to us that this insight has been neglected in the ongoing policy debate in Canada about the potential benefits and costs of higher tax rates for high-income earners. And it is certainly neglected in the Senate committee’s work on how to better support Canada’s charitable sector.

The Senate report is a powerful affirmation of Canadian civil society. The members have done an important service by drawing public attention to the role of our charities and the “unsung heroes [who] are essential to the well-being of our nation.” But it is not merely enough to laud their work. We need to create an environment where they can generate the resources required to deliver on their critical community-based missions.

This means ensuring that personal income tax rates on “super donors” are not starving them from funding. It should start with reworking the recommendation to review “existing tax measures available to individual donors” to also consider the role of rising marginal tax rates on charitable giving. Otherwise the social deficit will grow. And charities will be left “trying to do too much with too little.”

Sean Speer is a Munk senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and author of the MLI report, Harming Charity: The Potential Effects of High Personal Income Tax Rates on Charitable Giving.