Bill C-69 should be revamped in order to clarify key issues and avoid future project frustration, writes Joseph Quesnel. A good first step is the decision to proceed with consultations on this legislation.

Bill C-69 should be revamped in order to clarify key issues and avoid future project frustration, writes Joseph Quesnel. A good first step is the decision to proceed with consultations on this legislation.

By Joseph Quesnel, February 14, 2019

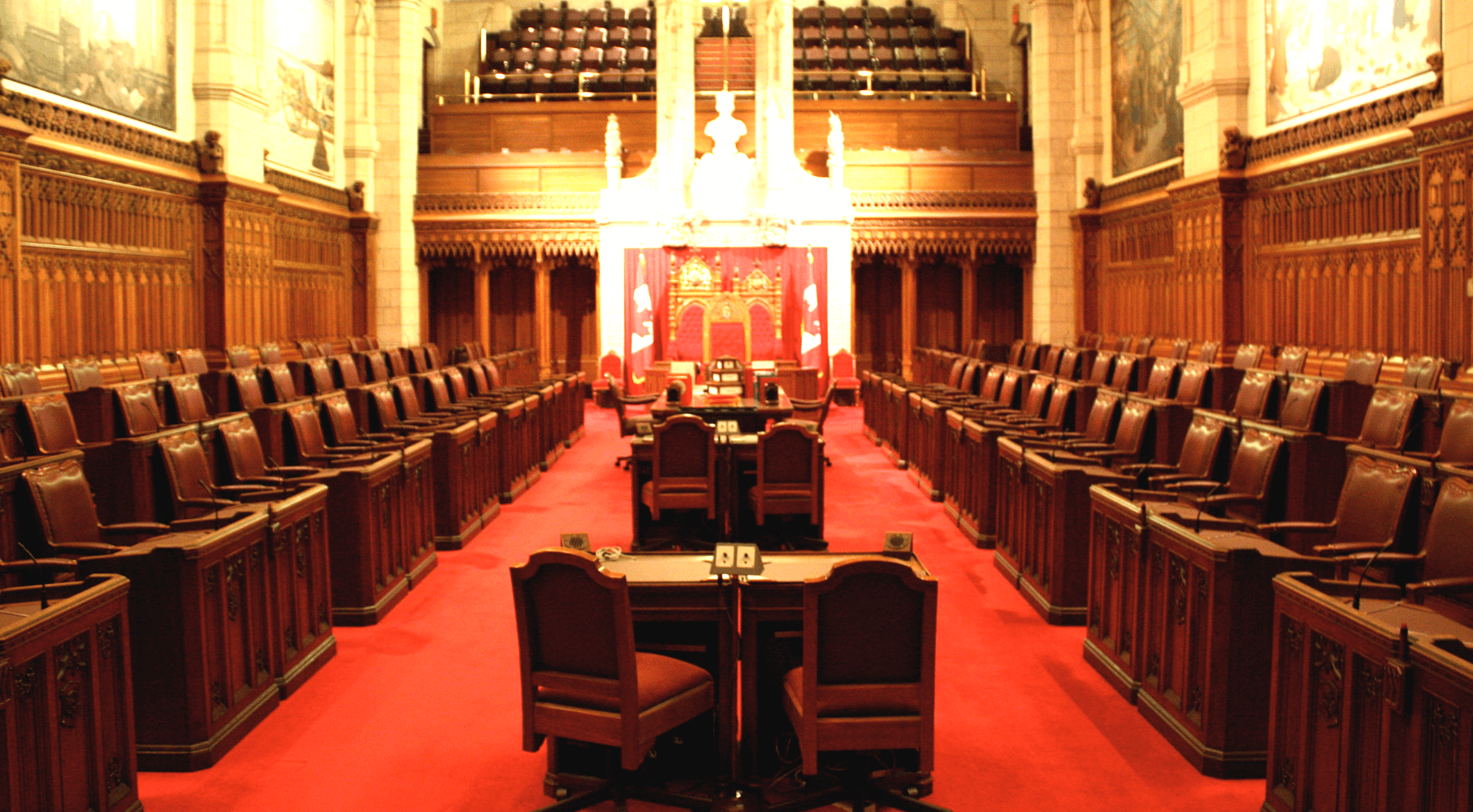

The Senate of Canada appears determined to serve as the chamber of sober second thought for Bill C-69, which is the Government of Canada’s sweeping revamp of environmental proposal processes. Good thing! While there are solid and important elements in the proposed legislation, the proposal is too big, too open-ended, and poorly timed.

Rarely have pieces of legislation attracted such odd alignments of supporters and opponents. Some First Nations and the Canadian Mining Association have backed the bill. So too, understandably, have environmental organizations. But other resource-dependent First Nations are pushing back, as are many companies and communities in the oil and gas sector.

For opponents of oil and gas development in Canada, Bill C-69 is a formidable weapon to use against the industry – one that further demonstrates the government’s weak response to energy development. In the case of the mining industry, the sector’s impressive efforts to work with local Indigenous groups means that existing practices are already at or beyond the bar established by Bill C-69.

In contrast, the oil and gas sector sees Bill C-69 as a uniquely and poorly timed intervention in an industry that – contrary to the expectations of most Canadians – has one of the most impressive pattern of engagement with Indigenous communities. As Indian Oil and Gas Canada likes to remind Canadians, there are over 130 oil and gas producing First Nations in Canada. First Nations are even contemplating buying into the Trans Mountain Expansion Project in an attempt to jumpstart that initiative and secure better markets and prices for their resources.

The decision by the Senate committee to take their environmental assessment reform bill on the road is fortuitous. If there’s environmental legislation that needs comprehensive consultation, this is it. While the bill contains improvements to the project assessment process, legislators and the Canadian public should still be greatly concerned about the legislation.

While the critic’s nickname for the legislation as the “no more pipelines bill” is a tad exaggerated, there is still potential for “mischief” and the bill adds further levels of complexity and expenses to project approval processes that are already grinding to a halt. The prospect for the loss of further billions of dollars in oil and gas investments looms large.

Opponents – mainly in the oil and gas industry – call for the bill to be completely withdrawn and reworked; others say it should be amended and saved. At this stage, the latter option is best, if only to allow a full assessment of its economic impact. This past week, the Standing Senate Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources examined and debated the merits of Bill C-69, with tense moments when certain senators grilled senior civil servants on the bill’s contents and likely adverse effects on an already-reeling Canadian energy sector.

The key strengths of the bill are its attempts to tighten and streamline the timelines for assessments. The new Act requires the participation of Indigenous communities earlier in the review process. Also, during a 180-day early planning phase, the newly-created Impact Assessment Agency must consult affected Indigenous parties. The Act also seeks to better identify Indigenous governing bodies that must be consulted, although adding more Indigenous groups to already complex consultations can be unwieldy and costly. The Act’s provisions for government funding for Indigenous peoples to help them engage in the assessment process is quite positive. Project proponents often complain that a problem occurs where they are not sure exactly who they need to work with on the Indigenous side. The bill also caps the length of a review at 300 days, a welcome change for industry but a concern for Indigenous groups facing pressure to engage on an externally imposed timeline.

So, the authors of the bill had good instincts in drafting it. It does address some of the long-standing concerns of industry. However, there is still potential to create mischief. C-69 will replace the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act with the Impact Assessment Act. This goes well beyond traditional environmental impact towards more nebulous and unquantifiable areas, such as health, gender, and even climate change.

The ambiguity thus created will likely lead to more assessment frustration and possible litigation down the road. During one of the recent Senate committee hearings, one senator on the committee asked about how environmental impact was defined or measured. One of the civil servant witnesses quickly pointed to scientific data on air and water quality. However, when it comes to climate change impacts, the appropriate metrics are unclear and hotly contested.

Efforts to mitigate climate change are important, but focusing on individual project assessments are not the place for addressing national and ambitious climate change targets. Dealing with climate change is more a regulatory and fiscal issue and it is one that must, to be effective, focus even more on consumers and energy users than producers.

Gender impacts are even more difficult to define and measure, even though it has become a favoured theme of the Liberal government. Some business groups argue that at minimum, if the government wants to keep gender impact as a project approval criterion, it must be clearly defined and measurable. This criterion seems well outside the scope of individual project assessment.

On the Indigenous aspects, there is much potential for assessment confusion and conflict. The first concerns the inclusion of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in the latest edition of the bill. Although only mentioned in the bill’s preamble, this can often be used in interpreting statutes later by courts. The chief concern about including UNDRIP is the provisions related to “free, prior, and informed consent” of Indigenous communities affected by projects. At a minimum, the bill’s references to UNDRIP should be qualified so as not to constitute a veto for Indigenous communities

The bill’s requirement to consider traditional Indigenous knowledge in assessments appropriately elevates local Indigenous experience and wisdom, but confusion remains about its relative weight when measured against peer-reviewed environmental science. On this the bill is unclear.

Lastly, the bill’s removal for any sort of “standing test” for public participation in the process vastly increases the chances for procedural mischief from project opponents. During the hearings on the bill, Alberta Senator Patti LaBoucane-Benson of the Independent Senators Group (ISG) – herself a Métis from Alberta – said it best: “However, by removing the standing test for participation, I wonder if the Indigenous voices for projects and against projects might be drowned out by the lack of a standing test so that anybody can participate. I wonder if the ability for resources and money to be put into the environmental side might drown out the Indigenous nations that are for projects, and oil and gas money might drown out the voices of the people who might be opposed to projects.”

With growing evidence of foreign-funded environmental foundations and groups becoming increasingly involved in obstructing Canada’s oil and gas sector, specifically Alberta’s oil industry, Canadian legislation must not allow these groups to frustrate the assessment process, marginalize Canadian voices for and against development projects, and undermine Canada’s economic interests.

In the end, legislators were quite right to engage with Canadians on this bill. They also must immediately amend the current version to clarify certain issues and avoid future project frustration.

But there is a final point worth considering. Bill C-69 and earlier environmental assessment legislation were designed to shape the review processes for individual projects, which are the focus on industry investment and community engagement. Bill C-69 is sweeping in reach and allows for every project approval to become a testing ground for the government’s sweeping agendas for climate change, gender, and environmental stewardship.

Each project, effectively, creates an opportunity to contest the very existence of the Canadian oil and gas industry. Canada has already become a high-risk venue for oil and gas development, as seen by the ravages to the sector caused by pipeline delays. Bill C-69 has the potential to create a permanent battleground for the sector, one that will scare off much-needed investment, delays production, and undermine the aspirations of numerous Indigenous groups seeking to build local economies. It is vital that the Senate takes the time and makes the effort to get this right.

Joseph Quesnel is program manager for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Aboriginal Canada and the Natural Resource Economy project.