Resolved, that the House of Commons of Canada desires to express its deep sense of the loss sustained by the Dominion and the Empire in the death of the late Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Tupper, Baronet, G.C.M.G., C.B. For many years a commanding fixture in the Parliament and Government of this Dominion in the confederation, expansion and development of which he played so great a part, Sir Charles Tupper’s name and career will ever be held by Canadians in intimate association with the progress and upbuilding of our country. Full of years and honours he has passed away, leaving behind him a long and impressive record of public service. The House of Commons avails itself of this opportunity to record its tribute of respect to the memory of one of its most distinguished members.

Right Hon. Sir Robert Borden (Prime Minister):

Mr. Speaker, Sir Charles Tupper entered public life in the province of Nova Scotia, of which he was a native, just sixty years before his lamented death last autumn.

For twelve years before Confederation he was a leading and commanding figure in that province, and his record and career in that provincial arena was what we might expect from one who displayed the great qualities which characterized him in after years in the wider Federal arena. Under his leadership the province of Nova Scotia entered upon a policy of free public education and of active railway development. His proposal for the union of the Maritime Provinces led to the holding of a conference at Charlottetown, at which delegates from the united provinces of Canada made their presence known, and in that way he directly led up to the great movement which resulted in the founding of this Confederation.

For nearly twenty years after Confederation he was a member of the House of Commons; and in that historic building on the Hill, now in ruins, his was one of the most commanding figures during all that time. He occupied many and important portfolios, and in 1886, or thereabouts, left the active discharge of political duties in this country to undertake the not less important duties of High Commissioner at London.

All those who had an opportunity of knowing his record and his work during that time agree, I am sure, that Canada could have had no more able, no more indefatigable, and no more faithful public servant than Sir Charles Tupper. I came into Parliament when the Government of which he was Prime Minister was defeated in 1896. I had known him, of course, but not intimately, as a great Nova Scotian, before I entered public life, and I can pay with every sincerity this tribute to his memory.

After serving under him for four years, while he was leader of the Opposition from 1896 to 1900, I was impressed and inspired with an even higher appreciation of his great ability, and an even greater admiration of his wonderful qualities than when I first, in the autumn of 1896, as one of his followers, took my seat in the House of Commons.

He had splendid qualities.

Not only his political friends, but his political opponents admired and paid tribute to him. He had a magnificent courage which never quailed before any danger, or in the face of any odds. He had a fine optimism. He was a firm believer in every sense in the resources of this Dominion, and in the greatness of its future.

His constructive statesmanship was evidenced in the various policies which he advocated for the development and upbuilding of the country. Whatever difference of opinion may have existed with regard to the wisdom of those policies, no difference of opinion could possibly have existed as to his sincere conviction that they were wise policies, or as to the remarkable ability and the wide vision which he displayed in defending them, both in Parliament and in the country.

He was undoubtedly a great protagonist, a man who, in the course of his public career delivered and received as many hard blows as any public man in Canada. But those who knew him intimately, not only his political friends, but his political opponents, will agree that, behind the vigour of his attack, behind the strong and earnest effort which he always brought to the advocacy of the policies which he upheld, there was absolutely no personal bitterness.

I had the privilege of an interview with him in the month of August last; I went to his home in the country, near London, for the purpose of seeing him before I returned to Canada. So far as his physical condition was concerned, he was, of course, very feeble, but I do not remember ever having spoken to him when his mind was clearer, his intellect more vigorous, or when he took a keener interest in the welfare of this Dominion, in its relations to the Empire, and in all that concerned the Empire at large. I spent about an hour with him on that occasion, and I came away inspired by the wonderful interest he displayed in the great events through which we are passing; by the boundless optimism and courage which still animated him with regard to the conduct of the war, with regard to our duty in the war, and with regard to its ultimate outcome.

In him passed away the last of the Great Canadians who took a leading part in laying the splendid foundations of this Dominion. He lived to see its boundaries extended to the great oceans on the West and on the North. He lived to see amply fulfilled the prophecies of early days which his far see-ing vision had inspired. At the last, as at the first, he held an abiding faith in the future of his country, and in its great destiny as one of the sister nations of this vast Empire.

Among the thousands who followed his mortal remains to their last resting place, I was privileged to be present. Years ago, he marked the spot where after life’s fitful fever he should sleep. There in the quiet God’s acre, in the suburbs of Halifax, where he desired to be laid at rest, he reposes by the side of her who for more than sixty years was his faithful companion and help-mate.

I trust that in the not distant future, upon Parliament Hill, there will arise a monument worthy of his memory; but, his most enduring monument will be the splendid record of achievement which commemorates his name in every province of Canada.

Upon the tablet above the tomb of the great architect of St. Paul’s Cathedral, there is written this inscription, “Si monumentum requires, circumspice.” So of him, one of the greatest founders of our Confederation, this may justly be said; if you seek his monument, look around you and behold all he wrought for the Canada that he loved so well and served so faithfully.

* * *

Right Honourable Sir Wilfrid Laurier:

Mr. Speaker, the House of Commons will honour itself, even more than it will honour the memory of Sir Charles Tupper, by testifying in the most solemn manner its appreciation of the many services and arduous labours of one who was in his time, and who must remain for all time upon its roll of honour, one of its most illustrious members, one who contributed in no small degree to make Canada what it is today.

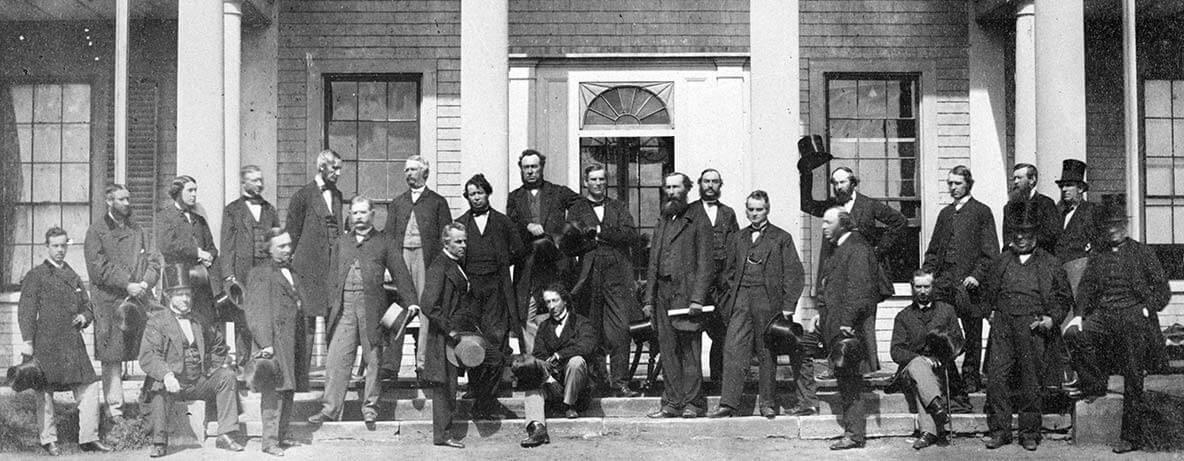

Sir Charles Tupper was the last survivor of that galaxy of strong and able men whom the Canadian people delight to honour with the name of Fathers of Confederation. Amongst the able men, who in the fall of 1864, assembled in the city of Quebec with the object of finding a basis of union for the then disjointed provinces of British North America, and whose united efforts brought forth the Canadian Confederation, the name of Tupper stands eminent among the most eminent.

Fifty years and more have passed since that date, and perhaps now, we are sufficiently removed from those stormy times to be able to frame a correct estimate of the part played by the statesmen of Canada in that intensely dramatic period of our history.

Undoubtedly to George Brown was due the first initiation of Confederation. He it was, who, by his strong and persevering agitation against the unwieldy union of Upper and Lower Canada, directed the destinies of Canada towards the Confederation of the older provinces of British North America.

It seems to me to be equally true that it was Sir George Cartier who first put the idea into shape when he set upon it the seal of his essentially practical mind, and brought to it the support of the one province which was material to the idea, if the idea was ever to become a fact.

By his talent and ability, Galt lent aid to the movement; still more did he do by obtaining for it the influential adhesion of the strong minority in the province of Quebec, of which he was the illustrious representative. It was the good fortune of Tilley to be able, almost from the first, to bring his province to support the idea with a minimum of division and difficulty.

Macdonald was the last to come into line. It is of record that for many years he objected to any change in [the] then existing condition of things, and only a few days before the coalition of 1864 he had almost passionately antagonized the very idea of a federal union. But when he did adopt the principle he became at once the captain and the pilot. It was his master hand that took hold of the helm, met difficulties as they arose, arrived at solutions of unforeseen obstacles, and steadily and unerringly directed the course until port was reached.

And what was the part of Tupper? In his day, this question of Confederation antagonized friends and divided foes. Now that we may look upon it in the calm judgment of history, it must be admitted, I think, that Tupper brought to the cause more firm conviction and took more chances than did anyone else.

It must be remembered that at that time Nova Scotia was completely against him, and that instead of using time and patience to win the province over to the idea of Confederation, he forced it into the union by the doubtful authority of a dying legislature. The grandeur of the idea strongly appealed to his mind, and he would not let pass the opportunity which if missed might not occur again for many years. If he erred at all, he erred because he loved not wisely but too well.

Indeed, in order to understand the action of Sir Charles Tupper at this important juncture in the history of our country, we must remember what was the chief characteristic of the man. In my judgment the chief characteristic of Tupper was courage; courage which no obstacle could down, which rushed to the assault, and which, if repulsed, came back to the combat again and again; courage which battered and hammered, perhaps not always judiciously, but always effectively; courage which never admitted defeat and which in the midst of overwhelming disaster ever maintained the proud carriage of unconquerable defiance.

This attribute of courage was the dominant feature of his whole public career, and perhaps never shone more prominently than in the manner in which he entered public life. It had not been his lot to be born to wealth or affluence. The son of a poor Baptist clergyman, he had succeeded by his own efforts in obtaining an education, and winning a diploma in the medical profession. He was a young practitioner, not known at all outside the precincts of his own town, and hardly known within them, when with splendid audacity he threw himself against one who was the darling of the people, the most potent influence in Nova Scotia and, perhaps the brightest impersonation of intellect that ever adorned the halls of a legislature in any part of what is now Canada.

Joseph Howe was then the member for Cumberland. In the province of Nova Scotia there is a tradition still extant, transmitted from father to son, and repeated at many firesides, that on one occasion, when Howe had addressed a meeting of his constituents and had brought his auditors to a pitch of enthusiasm even greater than that which his magnetic eloquence had ever before elicited, a young man rose from the audience to reply.

It is stated that Howe was somewhat surprised and perhaps not a little amused but at once yielded assent with something like patronizing condescension. If he was surprised at first, he had greater reason for surprise when he listened to the address of his hitherto unknown opponent. He found that in the speech of this young man there was meat and substance which moved the people and which gave cause for reflection and worry. The tradition further has it, that when Howe returned to Halifax he stated to his friends that he had met in Cumberland a young doctor who would be a tower of strength to the Conservatives and a thorn in the side of the Liberals.

The truth of his prediction was soon borne out, even at his own expense. At the elections which followed in 1855 young Tupper came forward against Howe in the county of Cumberland and wrested it from him. Howe at that time was at the zenith of his fame and it may certainly be said of his successful opponent that no one ever crossed the portals of any legislature through so wide an entrance.

Sir William Johnson was the leader of the Conservatives in Nova Scotia. He was a man of eminent ability, but being far advanced in years and in poor health, was only too glad to rely on the services of a young man of so much promise. From the day that young Tupper came to the fore in the legislature of Nova Scotia he became the guiding spirit of his party and the inspiration of all his followers.

Almost from that day his life became associated with the life of Canada, because it was only a few years afterwards, when he had become premier of his province, that the movement for Confederation was suddenly started. In that movement for Confederation, with all the excitement that it produced, and with all the agitation to which it gave birth, he found a genial field for his great parliamentary ability.

I have said that courage was his chief characteristic; but it was not his only characteristic. His mind had been cast in a broad mould. Whatever question he had to deal with he never approached it from the narrow sphere of parochial limitation; on the contrary, he approached it always from the broadest conception it was susceptible of. When I entered this House, more than forty years ago these were the two things which particularly struck me in him.

He was then in the prime of life and in the full maturity of his powers; he seemed to me the very incarnation of the parliamentary athlete, always strong, always ready to accept battle and to give battle. Though often my judgment was against him, in every case I could not say that he was animated by anything else than the broadest view of Canadian problems.

When Confederation had become an accomplished fact he rose to the front in the broader arena, just as he had taken the first rank in the legislature of his own province. From the day that he first entered the Chamber of the House of Commons, now unfortunately destroyed, his power was at once asserted and at once acknowledged by everybody.

He came into the Federal House under the most distressing circumstances, for in the elections of 1867, the first after Confederation, his whole province had gone against him; he alone had succeeded in retaining a seat. His conduct under these circumstances was worthy of all praise. He applied himself with unretiring zeal and unselfishness to the task of binding the wounds of his province, and of reconciling the people to the new conditions.

At first he met with but indifferent success; the feeling of resentment persistent only to be assuaged by the soothing hand of time. He had not the supreme gift of which Sir John A. Macdonald was pre-eminently the master: that of reconciling conflicting elements and, with the minimum of friction, of bringing them together as if they had always been one.

In this House his name must ever remain attached to two measures – measures very different in character, but each of which brought forth the particular qualities with which he was endowed; I refer to Protection, and the Canadian Pacific railway.

This is not the time nor the occasion to discuss Protection as an economic principle, but I think everybody, friend or foe, must admit that the introduction of Protection into Canada was, be it for weal or woe, was due to Sir Charles Tupper. Sir John A. Macdonald, as in the case of Confederation, had at first been rather indifferent and doubtful; Sir Charles Tupper never had a doubt. He it was who first became its advocate in this House, and he it was who carried on the agitation in the country; and in my humble judgment, great as was the personality and prestige of Sir John A. Macdonald, the victory of 1878 was due more to Sir Charles Tupper than to anyone else.

But it was not he, after all, who introduced the principle of protection as an actual measure. He had been the champion, but he was not its artisan in this House. That honour was reserved for Sir Leonard Tilley. But if Sir Charles Tupper did not introduce the protective measure in this House, it was simply because he did not choose to do so. He might have had the portfolio of Finance, but he rather chose the portfolio of Public Works, which at that time included railways.

With this portfolio he had the occasion to attach his name to another very great measure, the construction of the Canadian Pacific railway. All parties in this country had been in favour of a transcontinental railway, but no party had taken up the question with anything like serious earnestness until Sir Charles Tupper took it up with all the vigour of his nature.

He organized the syndicate which built the railway. These terms were much criticised as extravagant and yet though we may yet criticise the terms granted the syndicate as extravagant – such was the immensity of the enterprise that it was more than once on the eve of collapse. Nothing daunted the courage of Sir Charles Tupper. He never had any doubt of its ultimate success, and it was his good fortune to see all his predictions more than fulfilled.

Sir Charles Tupper had reached the zenith of his fame and power in this House when suddenly he withdrew from parliamentary life to accept the High Commissionership in London. The reasons which induced him to that step never were given to the public. But whatever they might have been, we who were his opponents thought that he had committed a great mistake. Undoubtedly his services in London were honourable and useful to the country, but in my opinion he was more fitted for parliamentary life, and his services to the country would have been still greater had he remained on the floor of this Parliament.

Though absent from Ottawa and in far-away London, his heart never deserted the field of his former activities, and whenever there was a battle to be fought he appeared on the scene, and, with his characteristic vigour, was always in the thickest of the fray.

Next to Sir John A. Macdonald, he was undoubtedly in his time the most powerful figure in the Conservative party. Indeed, it has always been a mystery to me and to those who sat on this side of the House that Sir Charles Tupper was not sent for when the old chieftain died. He was sent for at last, but then it was too late. The battle was already lost, and notwithstanding the vigour and brilliancy with which he threw himself into the battle, he could not redeem the fortunes of his party.

The public life of Sir Charles Tupper ended with the elections of 1900, when he had reached the age of almost eighty years. His strong constitution had at last been shaken by a life of arduous labour, and he withdrew to a well-earned rest. But though he retired from public life and [to] the seclusion of his family circle, he continued from day to day to follow with passionate interest the fortunes of Canada.

In that daily spectacle he had this great satisfaction, that the correctness of his estimate and of the resources of this country, when they were still unknown and undeveloped, was abundantly justified. When at last the end came his eyes closed upon a Canada whose population had doubled and more than doubled, whose national revenue had trebled and quadrupled, whose commerce had risen from a comparatively small figure to the billion dollar mark and more, whose products in agriculture and industry had reached figures that would have seemed fantastic in the first year of the Union – a Canada whose people were united even to the shedding of their blood in the defence and for the triumph of those principles of freedom and justice which the Fathers of Confederation had placed under the aegis of British institutions.

To say that the life of Sir Charles Tupper was without fault would be to say what cannot be said of any human life. But it must be said, and should ever be remembered, that but for the life of Sir Charles Tupper, Canada would not be what it is today.