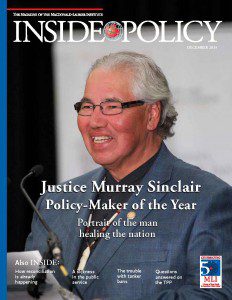

With the impressive impact of Justice Murray Sinclair’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Canadians want a new and more positive course for relations with Aboriginal peoples. Here’s how it’s already happening.

With the impressive impact of Justice Murray Sinclair’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Canadians want a new and more positive course for relations with Aboriginal peoples. Here’s how it’s already happening.

This is from the December 2015 edition of Inside Policy.

By Ken Coates, Dec. 16, 2015

After many decades of neglect and procrastination, Canada is finally open for reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Consider the impact of the Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission, chaired by Inside Policy magazine’s 2015 Policy-Maker of the Year, Murray Sinclair. The TRC travelled the country hearing from thousands of witnesses about the horrors they themselves endured after being removed from their families, and the lasting legacy of despair and dysfunction that grips so many communities. Contrast the nation’s reaction to the TRC with the much more tepid, long-delayed and largely inconsequential reaction to the even more extensive and detailed 1996 report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Canadians are, it seems, finally attentive.

The work of the TRC, whose final report will be released this month, has caused a tremendously positive public response, including the prominent place of pro-Indigenous policies in the 2015 federal electoral strategies of the Liberal Party and the New Democratic Party, and the post-election Liberal government policy. Let us not forget the important step taken by the previous government, in formally apologizing for the grievous harm caused by residential schools and commissioning the TRC. And then there were the strong words of Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, who described Canada’s past Indigenous policies as equivalent to a “cultural genocide”.

The phrase is apt. Residential schools were likely the most destructive public policies in Canadian history. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission has laid out for all to see the intensity of the residential school experience and the long-term legacy of this ill-advised, colonial system of cultural destruction.

After many decades of neglect and procrastination, Canada is finally open for reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

Surely the country can agree that a dramatically different approach is required. But it is not clear that all of the 90+ recommendations of the TRC, which range from a national day of recognition and public memorials to additional funding for the CBC, and nation-wide educational interventions, will solve the problems so carefully documented by the Commission. Many would be very positive. Some are cost-prohibative in the short term, or even impractical.

We should be concerned about the emphasis some have placed on government programs to fix these problems. Recall that it was big government programs – residential schools, but also the Indian Act, reserve creation and many other federal initiatives — that caused this mess in the first place.

We should be concerned about the emphasis some have placed on government programs to fix these problems. Recall that it was big government programs – residential schools, but also the Indian Act, reserve creation and many other federal initiatives — that caused this mess in the first place.

But the Trudeau government is determined to act, in keeping with its commitment to a more activist state. In a series of actions – symbolic, financial, practical and relational – Prime Minister Trudeau has made it clear that the Government of Canada intends to create new and different partnerships with First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples. That the public appears on board with this collaborative approach and that the Prime Minister has been warmly welcomed by the Assembly of First Nations and other Indigenous groups augers well for improved relationships and overdue progress on issues that matter deeply to Indigenous peoples in Canada.

It would be wrong for Canadians to assume that, with the federal government on the case, that non-Aboriginal individuals, communities and organizations can assume the role of spectators. Real reconciliation will have occurred when Aboriginal people have comparable educational outcomes, enjoy healthy and safe communities, have access to decent jobs, and experience a level of income and prosperity comparable to that of other Canadians. Substantial and sustainable reconciliation will be achieved when true equality of opportunity and a spirit of welcoming and inclusion exists across the land.

Reconciliation is, in practical and real terms, achievable in the short term. Indeed, even as the country focuses on the problems of the past, there are good reasons to see real progress and achievements in reconciliation already. Canadians can with cautious optimism, look to Aboriginal engagement in the natural resource sector as serving as the front lines of Canadian reconciliation.

Surely the country can agree that a dramatically different approach is required.

The newly elected Liberal government has, as noted, made positive overtures to Indigenous peoples, although with less attention than the previous administration to resource issues. The NDP government in Alberta, has shown willingness to support the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a commitment that is celebrated by Indigenous groups and is a matter of concern for resource companies, not for the spirit of UNDRIP but for the potential impact on development certainty.

The new approach by these governments to Indigenous affairs is matched by an aggressive agenda on climate change and environmental protection, which may be putting the brakes on global resource development. These initiatives, combined with declining oil prices and demand for commodities, have dampened enthusiasm for resource investments, ironic given the sector has demonstrated both engagement with Indigenous peoples and considerable success in responding to Inuit, Métis and First Nations expectations for sharing prosperity.

Canadians should remember that the country’s market economy emerged on the basis of long-standing and constructive partnerships with Aboriginal people. The collaboration was strongest in the transcontinental fur trade, but was also a key element in the West Coast salmon fishery, logging and mineral exploration. Three of the four people credited with discovering gold in the Klondike Gold Rush were Indigenous, after all. These connections are often forgotten. The social challenges that expanded in the 1960s and 1970s largely erased memories of extensive Aboriginal involvement in the resource economy.

Forty years ago, the resource sector was held up by Indigenous peoples as one of their top areas of concern. Aboriginal peoples were for too long on the outside looking in as resource development proliferated on their traditional lands. But recent years have been transformative times. Supreme Court cases from the 2004 Haida Nation decision that established the Crown’s “duty to consult and accommodate” Aboriginal communities on issues that affect them to the Tsilhqot’in decision on Aboriginal title 10 years later have given Aboriginal peoples tremendous new power to influence the terms of resource development. The resulting legal authority has been backed up by civil action, through the Idle No More movement, and through alliances with environmentalists against some resource projects.

Forty years ago, the resource sector was held up by Indigenous peoples as one of their top areas of concern. Aboriginal peoples were for too long on the outside looking in as resource development proliferated on their traditional lands. But recent years have been transformative times. Supreme Court cases from the 2004 Haida Nation decision that established the Crown’s “duty to consult and accommodate” Aboriginal communities on issues that affect them to the Tsilhqot’in decision on Aboriginal title 10 years later have given Aboriginal peoples tremendous new power to influence the terms of resource development. The resulting legal authority has been backed up by civil action, through the Idle No More movement, and through alliances with environmentalists against some resource projects.

There has been conflict, and many are still rightly cautious about the environmental and social implications of resource development. But there is also opportunity, as many resource firms have demonstrated a more open, collaborative approach.

The result on the ground for Indigenous peoples has been dramatic, and positive. There are now hundreds of collaboration agreements between resource developers and Indigenous groups, amounting to billions of dollars in jobs, skills training, business contracts, and payments to communities. More than 250 Aboriginal Economic Development Corporations are operating across the country, many with direct engagement in the resource sector. Many of these corporations have over $100 million in annual revenues; some are accumulating substantial assets that are being used to support regional businesses or to provide long-term financial foundations for Indigenous communities and governments.

Canadians forget how much has changed in recent years. Resource revenue sharing, once a distant dream, exists or is under development across much of the country. An increasing number of Indigenous communities are taking or considering equity positions on major resource projects. There are dozens of Aboriginal training and employment programs and there has been a dramatic expansion in Indigenous participation in college and university programs. The number, size and success of Aboriginal businesses has grown substantially, with many tied to the development sector, often capitalizing on preferential contracting arrangements that emerge from development agreements. Provincial and territorial governments have, in some instances, created positive space for Indigenous participation in environmental assessment, monitoring and remediation. While the collaboration may have been driven, in the first instance, by a combination of court decisions, an expanded sense of corporate social responsibility, and related business needs, it has produced positive results and growing business support. Reconciliation with Indigenous peoples – in the resource sector as elsewhere – is proving to be good for business and for all Canadians.

Canadians should remember that the country’s market economy emerged on the basis of long-standing and constructive partnerships with Aboriginal people.

Aboriginal participation in the resource economy has been challenged by the 2014-2015 downturn in the commodity markets and the resulting sharp reductions in exploration and development expenditures. These occurred at precisely the time that Indigenous groups were expanding their presence in the sector and developing substantial economic partnerships and collaborations. The current slump, critically, must be used as a time to formalize and stabilize relations with the resource sector, to convince Canadians of the value of long-term collaborations with Indigenous peoples and to demonstrate to Aboriginal communities that resource development does hold the promise of real and sustainable change. This is, in fact, the time to strengthen, renew and expand partnerships with Aboriginal communities. In doing so, we can demonstrate that reconciliation is real and possible. There is reason for optimism.

As reconciliation emerges through business engagement, several areas have shown considerable promise. Companies have discovered the benefits of showing a common face with their Aboriginal partners to government, and of demonstrating mutual support as a means of advancing specific projects. Collective responses to environmental concerns and protests, likewise, demonstrate common cause and provide a counter-balance to external criticism about projects located on traditional Indigenous territories.

Perhaps the greatest opportunity for ongoing collaboration rests with the intersection of the economic development corporations and resource firms. These Aboriginal run corporations already have billions of dollars in assets, with a rapid expansion possible. The firms are increasingly knowledgeable about the resource sector, want to diversity their holdings, and are looking to take a large share of the financial returns from the resource economy.

There are ways to improve on the partnerships that are leading the way for reconciliation with Indigenous peoples in Canada. It can be as simple as sharing what we’ve learned; making best practices in negotiated agreements available for all Indigenous groups and resource firms is an excellent way of spreading economic success and collaboration. Similarly, a number of resource companies have solid track records for capacity building, producing a larger skilled work force, providing long-term employment within the mine and development operations, and demonstrating the value of preparing companies for working with Indigenous people and cultures.

The largest resource projects, such as Vale’s Voisey’s Bay nickel mine in Labrador to choose one excellent example, are multi-generational in nature, providing a unique opportunity to develop long-term employment, training and investment plans. This requires, in turn, corporate engagement in regional Indigenous education and training in order to ensure that the firms have the skilled workforce needed to sustain operations in the future.

Indigenous peoples must be able to participate as meaningful partners throughout the development process. Collaboration from the outset – exploration, workforce development, environmental assessment, initial and long-term operations, environmental monitoring, post-project rehabilitation – would reassure Indigenous communities of the quality of the resource project and would maximize the potential return for the Indigenous peoples involved.

Reconciliation needs a new story, one that looks to beyond the problems of the past and that focuses on the achievements of the present and the prospects to do even better in the future.

General commentary on the Canadian resource sector focuses more on protests – a legitimate part of the contemplation of resource development – than on collaboration. Criticism of Canadian mines, pipeline companies, oil and gas firms, hydro projects and the like garners a lot more attention than joint business ventures, training and employment programs, and increased revenues for Indigenous communities. But this imbalance in public awareness has masked a promising story, one of true and widespread reconciliation, where Indigenous communities and governments have learned to work together and share, to a significant degree, the economic benefits of resource development

Reconciliation needs a new story, one that looks to beyond the problems of the past and that focuses on the achievements of the present and the prospects to do even better in the future. Canada can and must do much better than we have, and the Canadian public appears to agree. Reconciliation through resource partnerships may well lead Canada toward a more equitable and shared future.

Ken Coates is a Professor and Canada Research Chair in Regional Innovation in the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. He is also the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Senior Policy Fellow in Aboriginal and Northern Canadian Issues.