Why teenagers are skewing our picture of youth unemployment

OTTAWA, Oct. 22, 2015 – Youth unemployment isn’t getting worse. We’re just measuring it wrong.

That’s the conclusion economist Philip Cross reaches in a new paper for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Cross delves into the numbers to show that chatter about a “crisis” in youth unemployment fails to stand up to scrutiny.

To read the full paper, Serving Up the Reality on Youth Unemployment, click here.

The reason? The numbers on which this overheated rhetoric relies treat teenagers and those in their early 20s as equal.

They’re not.

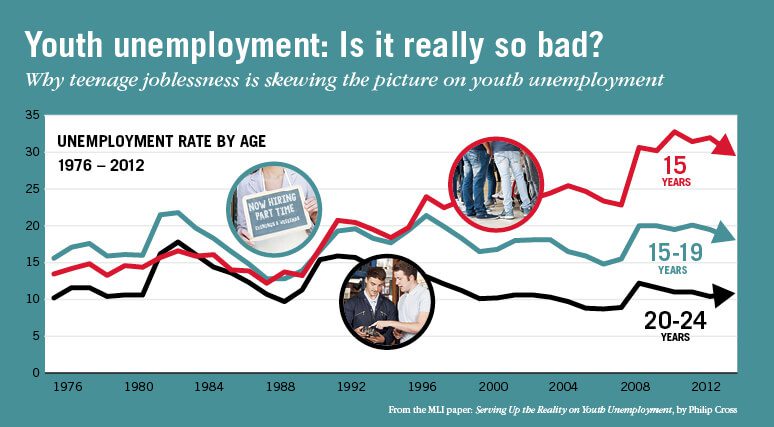

“Those who decry poor labour market conditions for young people are implying these trends disadvantage all the 2.9 million youth in the labour force, when it mostly affects the one million teenagers between 15 and 19 years,” writes Cross.

Teenagers versus young adults

This distinction is an important one. The challenges facing teenagers (those aged 15 to 19) and young adults (those aged 20 to 24) are different.

While a high percentage of teenagers are unemployed, they increasingly continue to live at home, attend school, and receive support from their parents.

“If (high unemployment among teenagers) is a problem, it is certainly a different one from the problems facing those young adults who are entering the workforce in earnest and preparing for careers, homes families, and the other challenges of adulthood,” writes Cross.

“If (high unemployment among teenagers) is a problem, it is certainly a different one from the problems facing those young adults who are entering the workforce in earnest and preparing for careers, homes families, and the other challenges of adulthood,” writes Cross.

When you subtract teenagers from the picture, the numbers show 20- to 24-year-olds are no worse off than they have been in recent decades. The 68.5 per cent employment rate for 20 to 24 year olds in 2014, for example, is nearly exactly equal to the average of 68.9 per cent over the past two decades.

The unemployment rate of 10.7 per cent in 2014 is close to the 20-year average of 11.0 per cent and far below peaks of 17.8 percent in 1983 and 15 percent in 1992.

The problem with 15-year-olds

Fifteen-year-olds in particular are distorting the youth employment picture.

Their unemployment rate has soared above 30 per cent in recent years, placing it well above the 13.2 per cent of 1990.

“Those who decry poor labour market conditions for young people are implying these trends disadvantage all the 2.9 million youth in the labour force, when it mostly affects the one million teenagers between 15 and 19 years”

This shouldn’t be surprising. Many provinces have labour laws, such as those that prevent teenagers under the age of 16 from working during school hours, that specifically restrict their ability to find employment.

Leaving the 15-year-olds out would knock at least a full percentage point off of recent years’ youth unemployment rates. In 2011 it would have lowered it by 1.4 points.

Leaving the 15-year-olds out would knock at least a full percentage point off of recent years’ youth unemployment rates. In 2011 it would have lowered it by 1.4 points.

Recommendations

Cross draws several recommendations from this study:

- Governments should consider returning to a separate and lower minimum wage for teenagers to address their high unemployment.

- Statistics Canada should start excluding 15-year-olds from its labour force survey. Fifteen-year-olds are an outlier and only distort our picture of youth unemployment.’

***

Philip Cross is a Senior Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He previously served as the Chief Economic Analyst for Statistics Canada, part of a 36-year career with the agency.

The Macdonald-Laurier Institute is the only non-partisan, independent national public policy think tank in Ottawa focusing on the full range of issues that fall under the jurisdiction of the federal government. Join us in 2015 as we celebrate our 5th anniversary.

For more information, please contact Mark Brownlee, communications manager, at 613-482-8327 x105 or email at mark.brownlee@macdonaldlaurier.ca.