This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Paul W. Bennett, March 17, 2025

The threats of Manifest Destiny, American annexation, and tariff war domination are hanging over us.

While most Canadian adults are resolute in resisting an American take-over, a January 2025 Ipsos Survey found the younger generation (ages 18-35) is far more open to the possibility and much more inclined, under favourable terms, to vote for joining the United States. Digging deeper, it becomes clearer why they are more susceptible to Trump and his appeals.

Our civic education is part of the problem, judging from the state of our current curriculum. Today’s students in high school and university are sadly unaware of their own history and democratic traditions. Knowing something about our political foundations, or the difference between a Tory and a Republican, is relevant, all of a sudden.

Youth disengagement

Civic education for school-aged youth is often presented as a remedy for generational disengagement. A December 2023 study, “Civics on the Sidelines,” conducted for the Canadian branch of CIVIX, raised more questions than it answered about the effectiveness of such programs. While citizenship education is “a priority on paper,” there’s a notable gap between the promise and the reality in today’s classrooms.

Student apathy, competing approaches, poorly prepared teachers, and fragmented social studies curricula jump out in that report.

Teaching politics and government to students is still considered the preserve of history and social studies teachers and their slice of the curriculum is getting smaller and smaller. Social studies teachers themselves are divided over the purposes of civic education and how best to deliver it in high school classrooms. Younger teachers, often lacking the subject background or teaching outside their field, tend to shy away from teaching our historical traditions, political structures, or filling the knowledge gap.

The curricular patchwork

Civics education tends to be hit-and-miss in K-12 education. Where civics is offered, it’s taught as an adjunct to social studies, but whether it is covered well is highly dependent upon the course structure and, to a large extent, the interests and capacities of teachers. Loose curricular integration tends to mean that teachers consider it optional. At the high school level, a specific civics course is only offered in three provinces: in grade 9 in Nova Scotia and grade 10 in Ontario and New Brunswick.

Three different approaches to teaching politics, government and citizenship, according to CIVIX, have emerged in recent years, ranging from teaching the foundations (why politics matter and how we are governed) to inculcating republican democratic values and processes to attempting to promote active engagement in “social justice” issues to effect change.

Teacher consultation groups cited in the CIVIX report revealed that much of the actual instruction tilts in the direction of the two models aligned with progressive pedagogy, namely the participatory democratic approach or the social justice approach.

The New Brunswick grade 10 Civics curriculum, introduced in September 2023, is typical because it takes an explicit “social justice” approach. It is essentially a one-shot deal that encourages youth activism, but is of little help in building student understanding of our historical tradition or in arming students with the political knowledge to meaningfully discuss the present threat to our sovereignty.

Decline of the youth vote

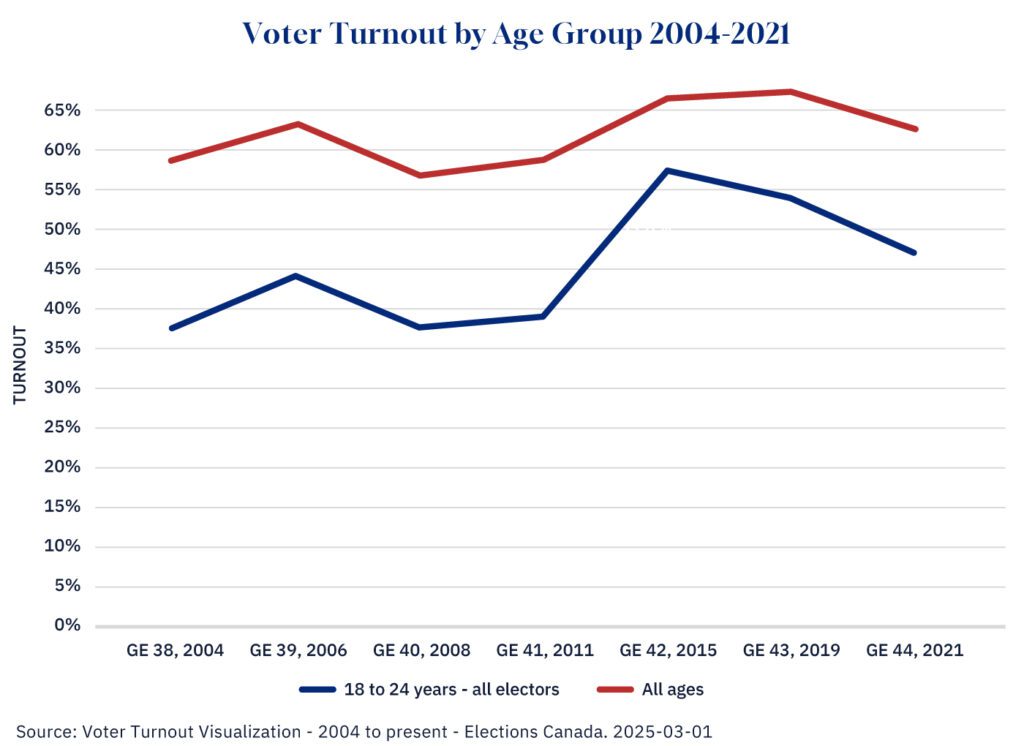

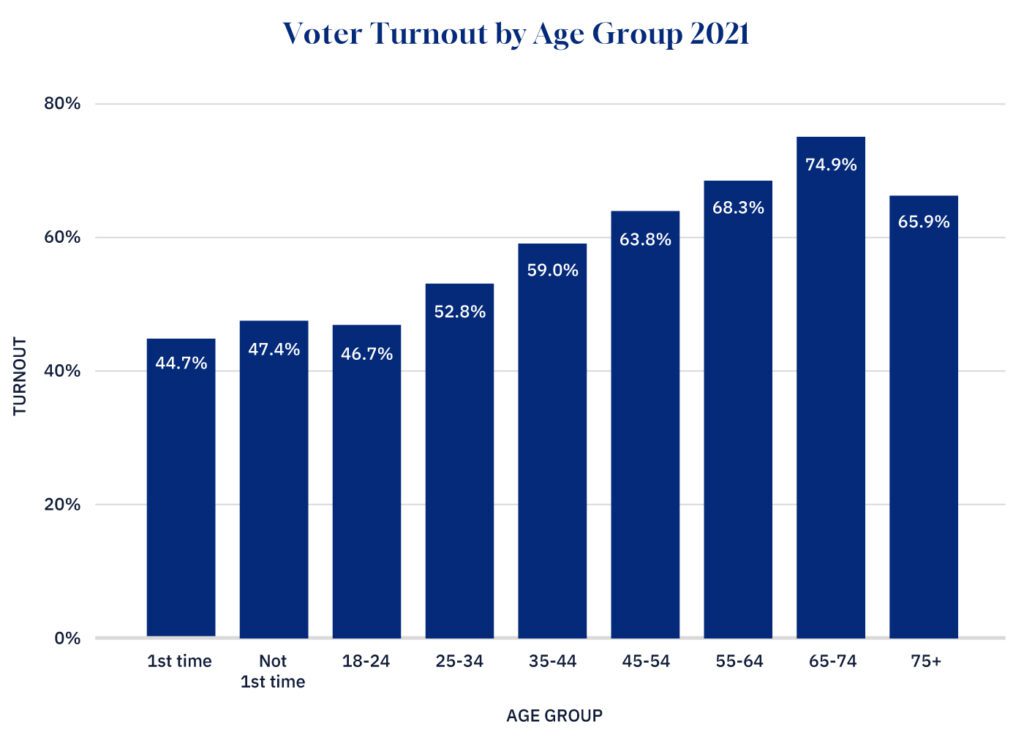

Voter participation in Canadian elections has been in steady decline over the past thirty years. That decline is most serious among youth, defined as young people between the ages of 18 and 24 who are eligible to vote. From the federal election of 1968 until 2000, voter turnout among youth cohorts trailed that of older, pre-baby-boomer voters by an average of twenty points. A notable spurt among younger voters in 2015, attributable to the appeal of Justin Trudeau, proved short-lived as it settled back in recent elections. In 2021, youth turnout plummeted to roughly 47 percent, 28 percentage points lower than the younger seniors.

A 2015 National Youth Survey, conducted for Elections Canada, identified two major barriers that prevented youth from voting—motivation and access—and identified the nub of the problem: fewer than half of youth (49 percent) see voting as a personal choice rather than a civic duty. Some 14 percent of youth (ages 18-24) were classified as “disengaged” compared to 8 percent of older adults.

Rethinking the purpose of civics

Traditional history and social studies courses attempted to spark students’ interest in public issues and to develop the political knowledge of future voters. While it was highly dependent upon the passion of the teacher, youth who voted in the federal election of 2015 were, in fact, more likely to attribute it to what they had learned about politics and government in high school or to the motivating factor of taking part in a mock election at school.

Steady declines in co-curricular activities have reduced the reach of public issues education. Mock parliaments, once wildly popular with aspiring young politicians, have all but vanished in high schools. The Ontario Model Parliament, for example, founded in 1986 and organized by and for high school students, lasted 30 years, and engaged over 7,500 students in the total political process before being absorbed into the Queen’s Park education program. School debating has declined, in spite of the herculean efforts of the Canadian Student Debating Federation and volunteer coaches, and fewer and fewer high schools have competitive teams.

Civic education organizations such as Toronto-based Samara Centre for Democracy’s Vote Pop Up program and Student Vote, organized by CIVIX with Elections Canada, emerged to fill the void and focus specifically on raising levels of student participation in elections. Classroom educators need to fully embrace those co-curricular initiatives from outside the school system.

Traditional civics provides the foundations of political knowledge necessary to take full advantage of political process simulations and mock elections. That approach is, it should be noted, at odds with current fashion aimed at empowering students with republican citizen’s rights values or tackling social justice issues in class, such as Indigenous claims, gender issues, and resolving lingering injustices.

Canada’s world has been turned upside down by Donald Trump’s return to the presidency threatening our national existence. It’s time for history and social studies classes, particularly in grade 9 and 10 civics, to get in the game instead of remaining on the sidelines.

Paul W. Bennett, Ed.D., is the director of the Schoolhouse Institute, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and an education columnist for Brunswick News/Postmedia.