This article originally appeared in National Newswatch.

By Patrice Dutil, January 13, 2025

It’s been said that those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it. But what of those that seek to erase it?

Justin Trudeau’s resignation as prime minister after nine years came just days before the 210th birthday of the most important of all the men who occupied that position – Sir John A. Macdonald.

Trudeau – unlike his father, Pierre – had no appreciation for Canada’s first prime minister. One of his first decisions was to rename the Langevin Block, the beautiful beaux-arts building across Parliament Hill where the Office of the Prime Minister is headquartered (it was dedicated to Hector-Louis Langevin, Macdonald’s chief lieutenant, a loyal and hard-working Quebec minister and Father of Confederation who had been wrongly accused of corruption).

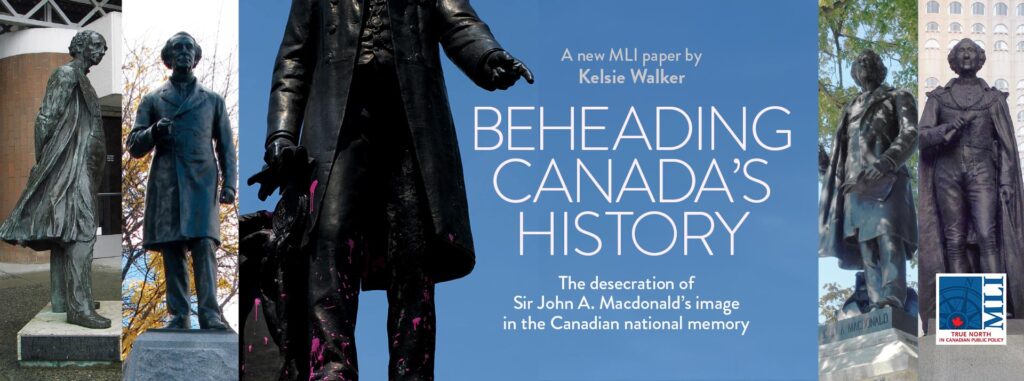

Trudeau worked to undermine and erase Macdonald’s legacy, including issuing a Cabinet order to review historical designations and plaques relating to Canada’s first prime minister in an effort to “decolonize” Canada’s history. When nine of the eleven monuments erected in honour of Macdonald were destroyed or removed, Trudeau did nothing. In fact, Trudeau showed precious little regard for his predecessors as he constantly apologized for what he considered their misdeeds. There is no better clue to his arrogance.

As if comparisons could be made! Macdonald dominated the politics and Parliament of his age by consistently and effectively responding to the issues of his day. He died while in office after winning a fourth consecutive majority – even taking more than fifty per cent of the vote in Quebec in 1891. Within years, grateful Canadians (not the state) raised money to build beautiful monuments to his memory in Montreal, Kingston, Toronto, and Hamilton.

In contrast, Trudeau leaves office with his reputation in tatters and his party sitting at an all-time low in popular support and facing catastrophe at the ballot box.

Perhaps, instead of denigrating and dismissing Canada’s first prime minister, Trudeau should have endeavoured to learn from his example.

Macdonald’s accomplishments have been largely forgotten, but they were as impressive as they were significant. He was the pivotal force behind the realization of the Confederation dream, playing a crucial role during the bitter campaign to unite the colonies of British North America between 1864 and 1867, and then leading the independence negotiations with Great Britain. He then settled the acquisition of the Northwest Territories, persuaded both British Columbia and Prince Edward Island to join Canada, and created the key institutions that governed the country in those difficult early years.

Justin Trudeau’s record will never match that of Canada’s first prime minister.

Some will say that this sort of comparison is simply impossible. The politics of today, for one thing, with its constant media attention, the endless demands on the state to deal with every issue imaginable, and the toxic political environment wrought by polarized opinions make this an insurmountable challenge.

It’s an idea worth contesting. Imagine a prime minister dealing with the problems of immigration and the challenge of integrating thousands of new arrivals, to dealing with a new president of the United States who doesn’t think much of his northern neighbour, to the demands of a foreign alliance calling on greater military contributions, to facing a revolt in Western Canada. Throw in a deadly epidemic to manage, a sluggish economy, swelling nationalism in Quebec, and a massive infrastructure project on the verge of collapse, and these calamities might overwhelm most politicians. Does it sound familiar?

Macdonald dealt with all the above at the same time, in 1885 – the most trying year of his life. In that year, the United Kingdom demanded that Canada supply men and materiel for its imperial campaign in Sudan. Macdonald refused but did allow Canadians to volunteer.

He also faced an incoming American president who sought to upend the commercial relationship between the United States and Canada. Macdonald negotiated hard with President Grover Cleveland, insisting that Canadian demands be met.

Meanwhile, as a smallpox epidemic swept Quebec, Macdonald ensured that vaccines were available. (Of the more than 6,000 who died, most were French-Canadian children who were not inoculated.)

In the West, Macdonald confronted and defeated Metis leader Louis Riel’s forces during the North-West Rebellion. After Riel was hanged for treason, Quebec nationalists unleashed a vehement campaign against Macdonald and his government. It did not last, as Macdonald quietly made his case. Quebec voters supported him in the election held fifteen months later.

Not least, the Canadian Pacific Railway was on the road to bankruptcy in 1885, threatening the future of Macdonald’s cherished intercontinental line. The Prime Minister sold his colleagues on the advantages of supporting the CPR to its completion. The benefits were felt almost instantaneously when the last spike was driven in November of that year.

How did the then-70-year-old Macdonald manage all these crises? Rather than rushing into quick fixes, he compartmentalized each challenge, and patiently waited for the right window of opportunity to open so that a solution was achievable. In many cases, he had anticipated the crises in advance and laid a policy groundwork that enabled his solutions. In contrast with his political rivals, Macdonald offered competence and vision.

Indeed, despite modern accusations to the contrary, Macdonald was a truly progressive politician in his day – a man who sought compromise and genially combined both liberal and conservative impulses when it came to determining public policy. (He even sought to extend the vote to both women and Indigenous men in 1885. He failed in the former but succeeded in the latter.)

The year 1885 was exhausting, but Macdonald displayed a master class in leadership that Canadians appreciated in his day. When Macdonald died in office in 1891, most Canadians wept at his loss. This is something to remember as Trudeau takes a final bow.

Macdonald still has lessons to offer today’s politicians. Sure, they can obsess about their images and their social media profile, but nothing beats good honest government and smart politics. That was one of Macdonald’s key lessons: work with colleagues in the party and in Cabinet to develop ideas, respect their views, and then do your level best to deal with the issues. Canadians can tell if they are getting good government. Despite all the efforts spent over the past decade to demean his legacy, Sir John A. Macdonald may well have the last laugh.

Patrice Dutil is a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. His new book is Sir John A. Macdonald and the Apocalyptic Year 1885 (Sutherland House).