This article originally appeared in the Epoch Times.

By Peter Menzies, February 9, 2024

Hands up everyone who thinks it’s a good idea to allow kids to watch pornography?

Anyone? No? Sure? Anyone?

I didn’t think so. Neither do I. But that’s exactly why Canada is on the cusp of passing what could turn out to be its most invasive, privacy-threatening, internet-freedom suppressing, anti-free speech legislation yet.

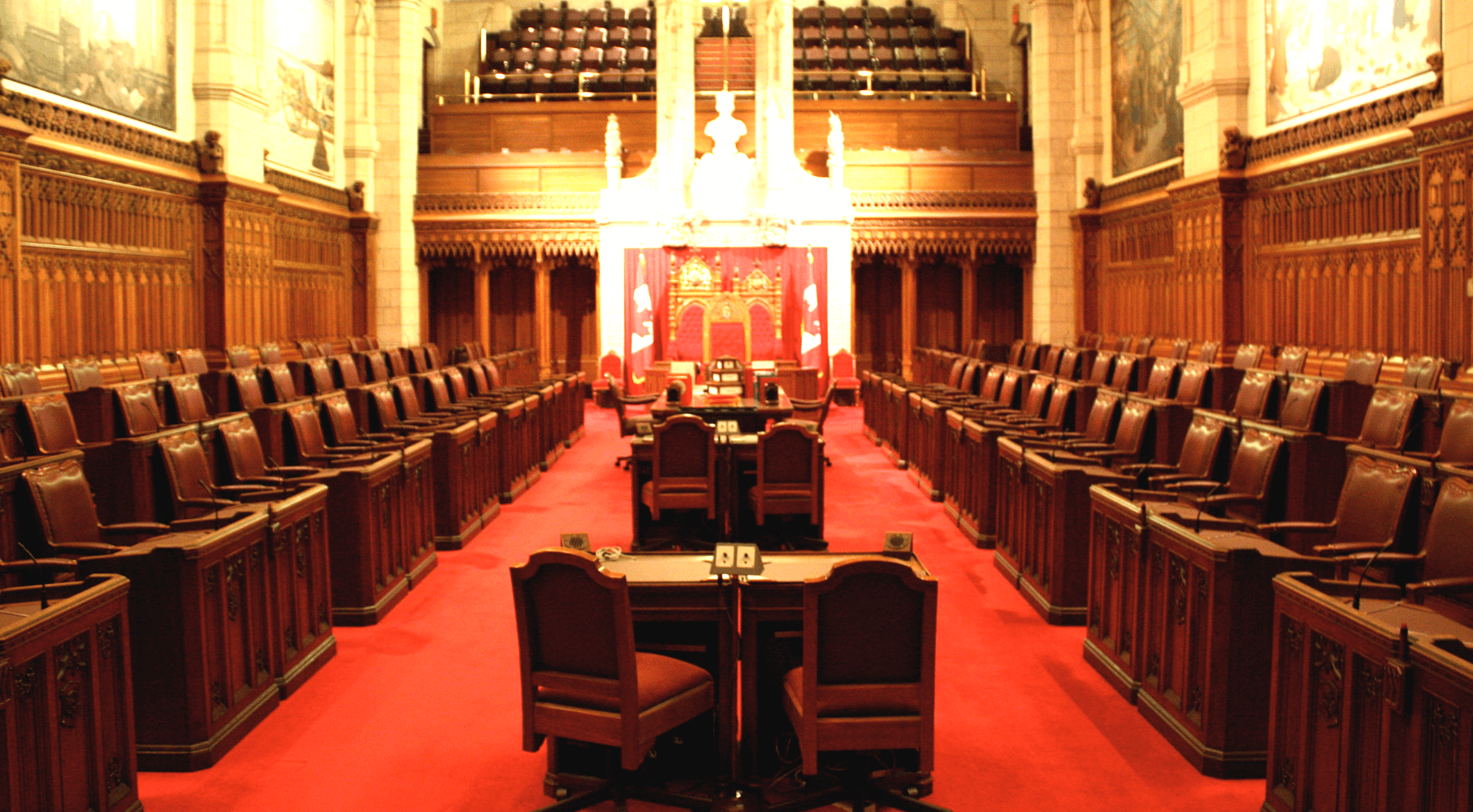

And all in the name of a good cause. Welcome to Bill S-210, the Protecting Young Persons from Exposure to Pornography Act. It’s a private member’s bill introduced by Sen. Julie Miville-Dechene. It has passed three readings in the Senate, where it was introduced, and is now in committee with the House of Commons, having sailed through its first two readings there.

It’s a bill with significantly frightening flaws and truly problematic potential. But it might very well become law because there aren’t enough politicians out there with the guts to oppose it.

Halifax privacy lawyer and law school lecturer David Fraser calls it a “clear and present danger to a free and open internet” that “shockingly” has gained political traction.

University of Ottawa law professor Michael Geist describes it as the “most dangerous Canadian internet law you’ve never heard of.”

“While there are surely good intentions with the bill, the risks and potential harms it poses are significant,” he wrote on his blog.

The internet freedom advocacy organization OpenMedia is equally appalled.

“If S-210 is passed without major fixes, Canadians could see most internet services require us to provide a government-issued ID to log on, have our faces repeatedly scanned and stored in leaky databases to simply live our online lives; and see many websites and services that refuse to participate in this draconian system blocked in Canada altogether,” OpenMedia’s Matt Hatfield states.

“Protecting kids is important, but not at this cost.”

Sen. Miville-Dechene, who was appointed by the Trudeau government in 2018, certainly didn’t set out to destroy internet freedom. She genuinely just doesn’t want kids being prematurely exposed to porn (we’re not talking grandpa’s Playboy magazines here) and having their lives distorted by it.

But her bill lacks the finesse required to achieve that goal. For instance, it refers to “sexually explicit” content, a definition that could just as easily apply to scenes in “Romcom” movies or even television programs.

That’s one of the reasons why 133 Liberal MPs voted against the bill in December and why a department of Heritage spokesman told the Globe and Mail: “We share the goal of a safer internet experience for children and youth. However, this bill is fundamentally flawed.”

That’s right, the issue this time when it comes to a controversial internet bill involving massive overreach and data farming is not Justin Trudeau’s minority government—it’s Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives along with Jagmeet Singh’s NDP and the Bloc Québécois. None of them want to be accused of opposing it and all of them are happy to let the Liberals look like the ones who do. And if all of them support it, it doesn’t matter what the Liberals do—Bill S-210 will become law.

But just because the intentions are good—as the song goes, “Oh Lord, please don’t let me be misunderstood”—doesn’t mean the legislation is appropriate.

Pornography—not just sexually explicit material/erotica—has been available to Canadian cable customers for decades via subscription. And it is made so without a requirement for proof of age verification. The homeowner/cable subscriber has always been trusted by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to manage its accounts. Additionally, parental controls are available on most home routers via your internet service providers as they are on smartphones.

Bill S-210 removes the responsibility for management of content available to children from parents and puts it in the hands of the state. You may agree or disagree with that approach, but there is no question that such a move within the context of this bill would have severe consequences when it comes to freedom of expression.

As Emily Laidlaw, a University of Calgary law school associate professor, put it in her assessment of Miville-Dechene’s legislation, “Prior restraint is the worst form of censorship, because it prevents the communication from happening in the first place.”

There is considerable evidence that exposure to pornography at the level it exists today is harmful to children. Laidlaw points to a British study by the UK Children’s Commissioner that puts the average age at which a child is first exposed to pornography at 13, with 10 percent viewing it before the age of 9. The U.S. surgeon general has issued an advisory on negative impacts of social media use on young people. Still others argue that child-proofing of the internet, while possible for parents within their home, is impossible from a regulatory perspective. Australia, as Laidlaw reminds us, explored age verification for porn sites but then abandoned it.

In the case of Bill S-210, Canada would be well-advised to do the same.

Peter Menzies is a senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, an award winning journalist, and former vice-chair of the CRTC.