By Jerome Gessaroli

June 10, 2022

How long (How long) will interest rates stay low?

That’s the question, the whole world wants to know

How long (How long) will interest rates stay low?

It seems like if they’re going up, they’re going pretty slow

‒ Merle Hazard (2016), country singer/economist

Introduction

Canada’s strong economic recovery from the pandemic induced shutdown has come with inflation the country has not experienced in over 30 years. The pandemic economy has indeed posed challenges for the Bank of Canada. It correctly acted to put into place programs that ensured credit market liquidity. It also reduced its policy interest rate from 1.75 percent to 0.25 percent. The bank soon after began quantitative easing (QE), which further lowered medium- and longer-term interest rates, allowing for very low borrowing costs. QE facilitated a large increase in the money supply and set the stage for the federal government’s massive stimulus program.

Who has the economic crystal ball?

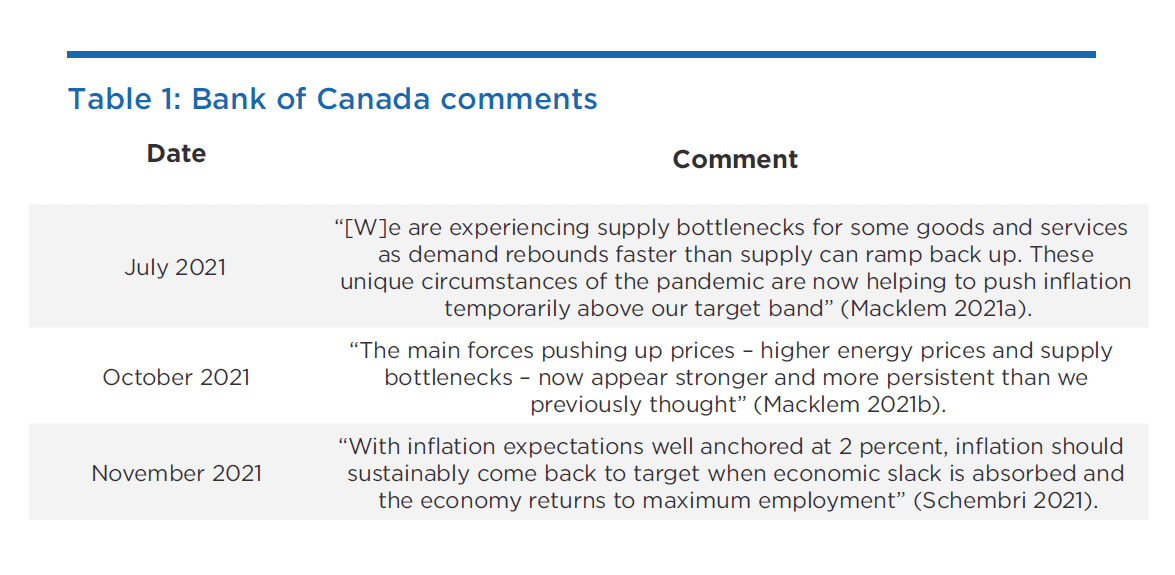

What is more puzzling, however, is the bank’s handling of inflation after the economy re-opened. The central bank has often reiterated its commitment to maintain low inflation, consistent with its past target of 1 to 3 percent, allowing for some short-term flexibility. However, it has underestimated inflation throughout 2021. Table 1 shows some of the Bank of Canada’s thoughts on inflation.

Even as high inflation numbers came in, and acknowledging additional inflation challenges, the central bank’s revised inflation forecasts were still overly conservative. Table 2 shows how the Bank of Canada consistently under forecasted 2021 year-end inflation. The bank also maintained its 2022 forecast at 2 percent until it finally revised its forecast upwards to 4.2 percent. While no one knows what final inflation numbers will be for 2022, their 4.2 percent forecast seems optimistic. To the Bank of Canada’s credit, it slowed down its quantitative easing earlier than the US Federal Reserve.

While some economists expected inflation to be relatively subdued and transitory, others were more concerned. In February 2021, quite early in the recovery, Scotia Bank economist Derek Holt wrote that:

growth rates in broad money supply are shattering multi-decade records…if this truly proves to be a transitory shock marked by one really bad quarter for GDP last year…then this kind of sustained monetary policy expansion is extraordinarily aggressive. … Until the present time, we’ve never had a period like this that can be modelled within-sample by way of the inflation consequences because we’ve never had a period in which central bank balance sheets have expanded as strongly with no countervailing forces. (Holt 2021)

A June 2021 RBC report wrote that “Underlying inflation pressures also firmed with 54% of goods and services within the CPI basket posting increases of more than 2% … Historically, when market-based and surveys of inflation expectations increase, actual prices and wage demands follow suit” (Wright, Desjardins, and Janzen 2020).

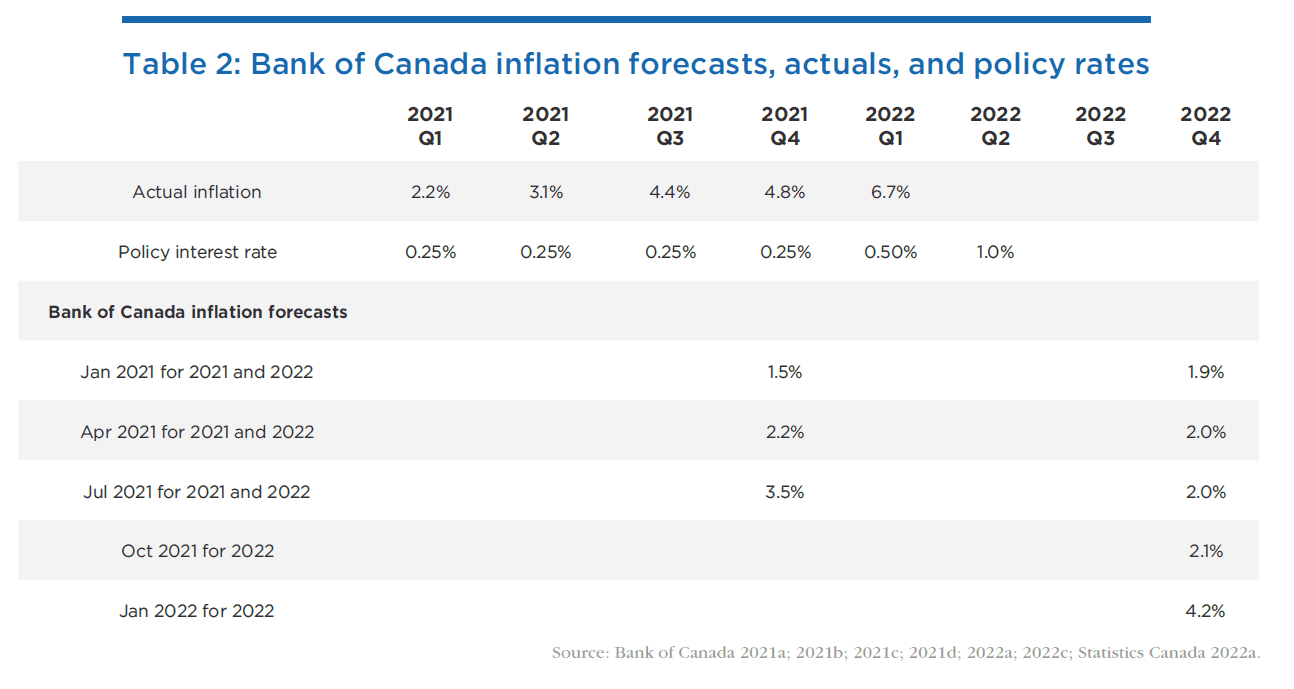

Several central bank and government actions are of note. Figure 1 shows the rapid increase in the Bank of Canada’s assets over a one-year period, beginning in March 2020. Buying $380 billion in government securities lowered interest rates across the yield curve and injected mass liquidity into the economy. In 2020, the top three federal government COVID-related benefit programs provided $82 billion to individuals (Statistics Canada 2022, 2). During the same time, many businesses shuttered. Even those remaining open reduced their output because of pandemic-related bottlenecks. The government added large stimulus on the demand side, when much of the money could not be spent due to the lockdown.

It’s important to note that some government support to laid-off workers and some businesses whose cash flow abruptly stopped was useful. However, the stimulus overall was massive and significant funds went towards savings and paying down household debt. Both these became big reservoirs, which households started using when the economy reopened. Stanford economist and Hoover Institution senior fellow John Cochrane explains the situation this way: “A pandemic is, to the economy, like a huge snowstorm. Sending people money won’t get them out to closed bars, restaurants, airlines and businesses” (Varadarajan 2022).

While supply constraints are still an issue (such as China’s continuing COVID lockdown policies), inflationary pressures are more than transitory. Supply chain issues affect the price of certain goods, not all. In those cases, the prices of supply constrained goods will rise relative to others. But our current inflation is showing broad-based price increases, suggesting inflation is coming more from the demand side of the economy (Cochrane 2022).

The central bank’s response to inflation

The central bank is taking a cautious approach to tackling inflation. Usually, to bring down inflation, there should be a positive real interest rate yield (with the real interest rate yield being the nominal interest rate minus inflation). Based on a 4.7 percent core inflation[1] and an extra 0.5 percent, the nominal rate would be 5.2 percent. The Taylor rule, a well-known concept in monetary economics, is another guideline used when considering the bank’s policy rate.

r = p + 0.5y + 0.5(p – 2) + 2

Where

r = nominal policy interest rate

p = the rate of inflation

y = percent deviation of real actual GDP to full employment GDP

The 2 percent in the formula is the bank’s target inflation rate. Based on a 4.7 percent inflation rate, and assuming the real actual GDP equals full employment GDP, the policy interest rate would be:

r = 4.7% + 0.5(0) + 0.5(4.7% – 2.0%) = 6.05 ≈ 6.0%.

Both estimates, 5.2 percent and 6.0 percent, are a far cry from the current policy rate of 1 percent. Even factoring in expected rate increases, which will bring the rate to 2.5 percent before the end of 2022 (TD Economics 2022), still suggests an underwhelming response to tackling inflation.

The bank’s cautious policy interest rate reflects their inflation forecast for 2023, which they expect will substantially ease. They write that the “decline reflects decreases in energy prices, a dissipation of global supply chain constraints and a rebalancing of supply and demand in the Canadian economy” (Bank of Canada 2022b, 1). The central bank is still assuming that transitory issues such as energy prices and supply chains (both supply side factors) are behind much of the inflation. If, however, inflation is due to demand for goods and services, driven by money supply growth and government spending, the central bank’s interest rate moves will be insufficient.

Bank of Canada expectations of the market’s expectations

Inflation targeting by the Bank of Canada is used to manage the market’s inflation expectations. The bank clearly and regularly communicates that one of its priorities is to keep the overall inflation rate between 1 to 3 percent, with a midpoint target of 2 percent. The bank’s message is simple: if inflation goes beyond the 1 to 3 percent band for more than a short period, it will raise (or lower) interest rates to bring inflation back within its target range. Besides clear messaging, the bank’s willingness to act must also be credible. In other words, the market must believe the bank will move interest rates in response to higher or lower inflation.

Expectations are essential to maintaining low and stable inflation. If market participants expect inflation to remain low, then when prices increase over the short-term, the market will collectively make business decisions in a manner that keeps inflation low. Consumers will not change their purchasing behaviour by buying earlier, in anticipation of product prices increases. Workers will not demand large wage increases to keep up with inflation, and producers will not increase prices, based on expectations that input costs will remain unchanged. Since 1991, the Bank of Canada has successfully used inflation targeting to keep the market’s inflationary expectations anchored at 2 percent (Macklem 2021c).

Is the cure worse than the disease?

While there is a strong case for higher interest rates, the Bank of Canada knows the blunt instrument it carries with its policy interest rate. Raising rates can lower inflation, though often at the cost of an economic recession. In 1981, in response to particularly stubborn inflation, the central bank had to raise its policy rate to over 21 percent, before inflation fell. Canada subsequently suffered its worst recession since the Second World War, with unemployment reaching 12 percent. The conditions in 1981 are not the same as the present. Rather, it simply illustrates the widespread impact high interest rates can have on the economy.

The federal government spent much treasure in 2020 and 2021 to avoid a painful recession with many job losses. Federal debt increased by 65 percent, or $475 billion to $1.2 trillion, over the two-year period (Canada 2021a; 2021c, 23), with significant amounts spent on pandemic stimulus. The Bank of Canada surely wishes to avoid carrying out rate hikes that would lower inflation but simultaneously raise unemployment and undo all what the government spent billions of dollars trying to avoid.

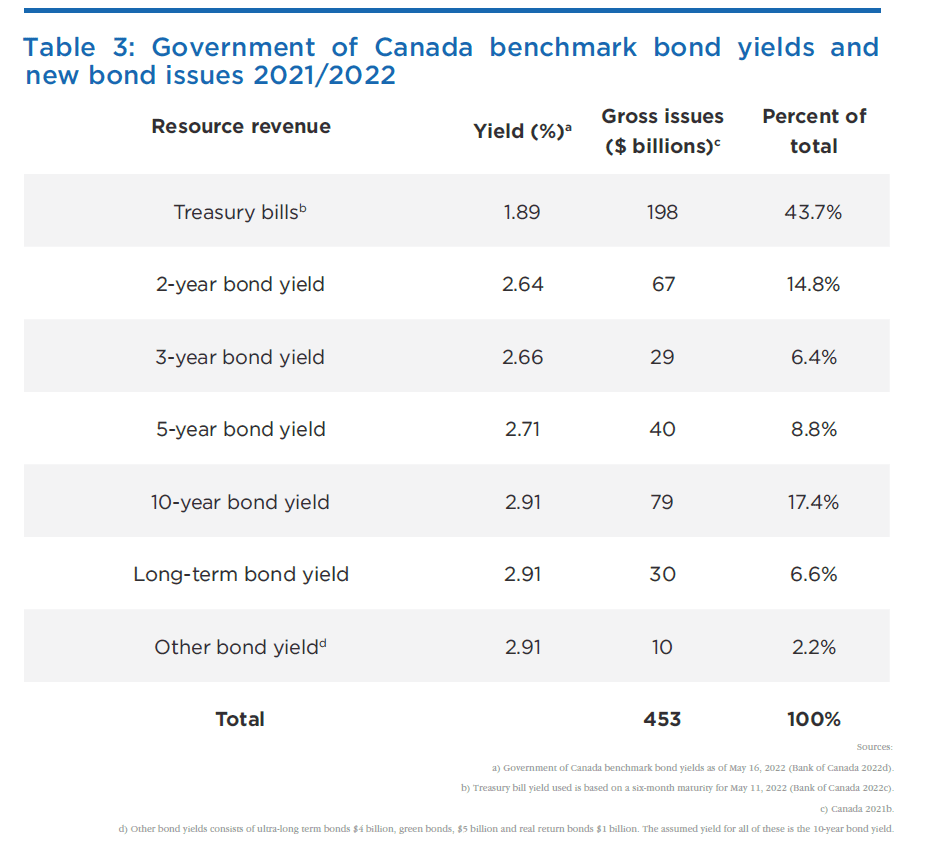

Another consequence the central bank wants to avoid is burdening the federal government with significantly higher interest charges. Federal government gross debt for 2021-22 totals about $1.2 trillion while interest charges are $24 billion (Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer 2022, 5). The government plans on issuing over $453 billion of market debt this year (Canada 2021b). If the Bank of Canada did increase interest rates so there was a positive real yield of 0.5 percent (as discussed earlier), the incremental debt charges for the new bond issues in the 2021-22 fiscal year alone would be approximately $12 billion or 50 percent more than the forecasted charges (see Appendix 1 for details). This would then force the government to cut $12 billion from its budget or allow its deficit for the year to increase by that same amount. Provincial government budgets would suffer a similar fate.

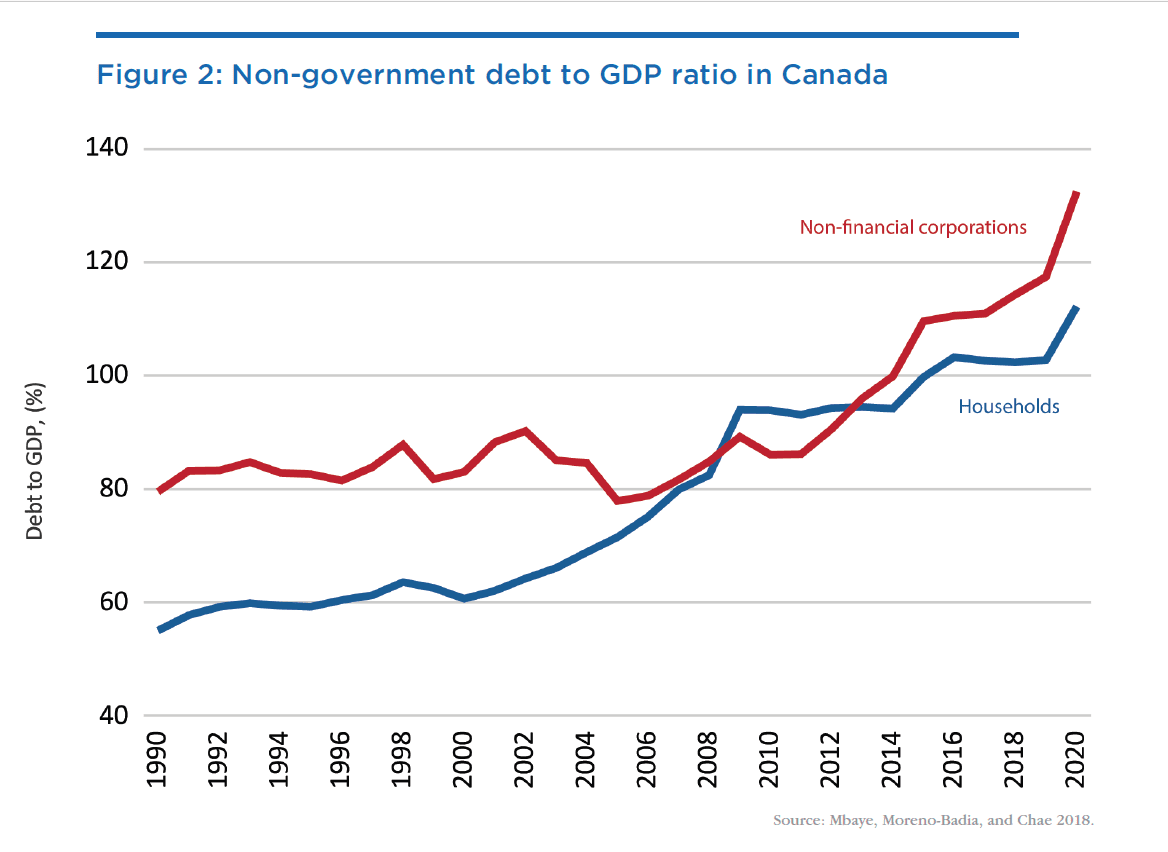

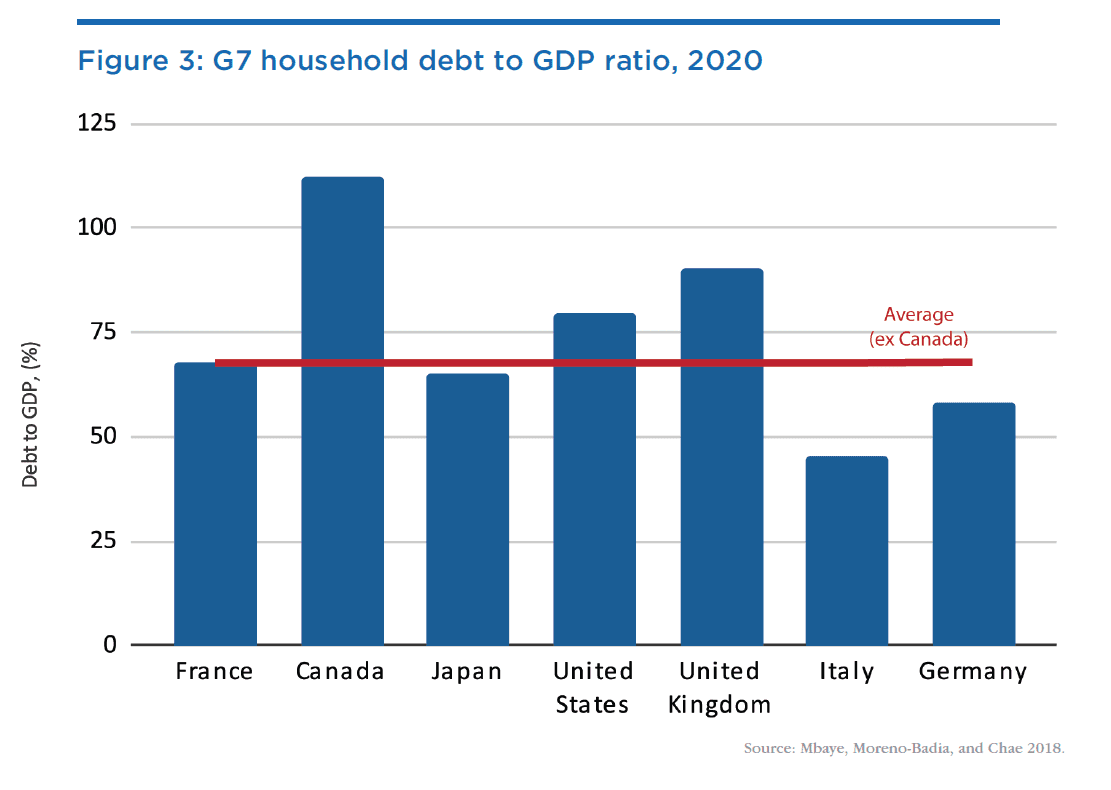

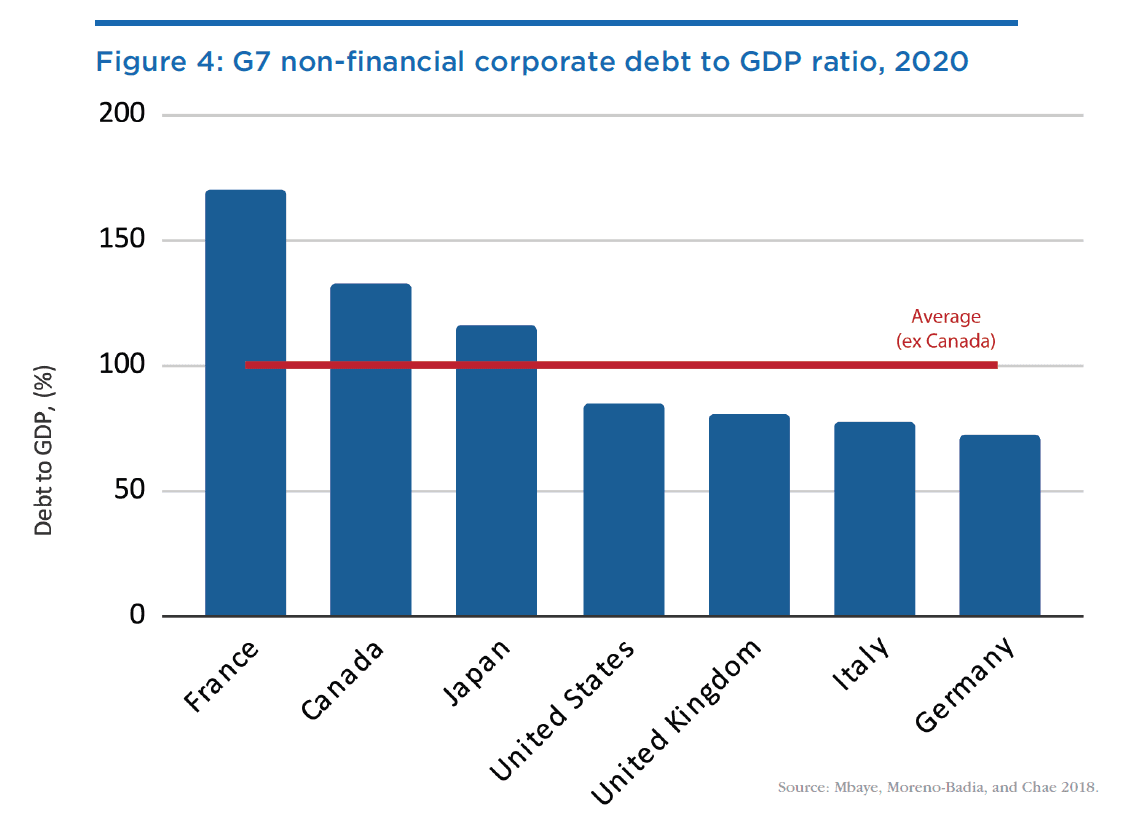

As shown in Figure 2, there has been a marked increase in household and nonfinancial corporate debt as a proportion to GDP. Figures 3 and 4 show Canadian households have the highest relative proportion of debt to their economy than any other G7 nation and is second highest for corporate indebtedness. Increasing interest rates therefore would have a disproportionate impact on households and businesses than say in the United States. These debt levels likely make the Bank of Canada even more reticent to move more aggressively on interest rates.

If not interest rates, then what?

The Bank of Canada’s recent modest interest rate hike is consistent with its hesitancy to use its interest rate tool extensively, as it could come at a high cost to all major parts of the economy. Instead, the bank is trying to manage inflation through its inflation targeting policy. While the bank’s inflation targeting message has remained clear in 2021 and 2022, its timid moves on interest rates belie its words. The Bank of Canada is leaning on its credibility of past inflation targeting success to convince market participants to keep inflation expectations low. If the bank succeeds, it will dampen inflation and simultaneously avoid collateral damage that higher interest rates would have otherwise caused.

The weakness to this approach is that the longer core inflation exceeds the bank’s target inflation range, the less credible and effective the bank’s inflation target messaging becomes. And when that happens, market participants will revise upwards their inflation expectations. If businesses expect 5 percent inflation, then they will raise prices by 5 percent. If workers and unions expect 5 percent inflation, then they will demand 5 percent wage increases in their collective agreements. If consumers expect 5 percent inflation, then they will be more likely to purchase goods such as automobiles earlier, to avoid paying more later.

When this occurs, higher inflationary expectations become entrenched in the economy, and lowering inflation becomes much more difficult. There is prima facie evidence this may be occurring. For instance, the Public Service Alliance of Canada is asking for a 4.5 percent wage increase annually in a three-year contract (Pittis 2022). The BC Government Employees Union is holding a strike vote to back up their demand for a 5 percent, or a cost-of-living wage adjustment, annually for the next two years (McSheffrey 2022).

The Bank of Canada realizes that their combination of modest rate hikes and messaging is not having the desired effect. It has now begun to use “interest rate guidance”[2] to strengthen its message and credibility to keep inflation expectations in line. With interest rate guidance, the bank more aggressively communicates its future interest rate moves, so the market will take future higher (or lower) interest rates into their current decision-making. The Bank of Canada said “it is important that Canadians understand that interest rates are on an upward path so that they can plan according” (Gordon 2022). While it signals the bank’s likelihood of future rate changes, it does not necessarily align the market’s inflation expectations with those of the central bank.

Conclusion

The Bank of Canada faces a real challenge. Very loose monetary policy consisting of near zero interest rates, bond buying (quantitative easing), and money supply expansion, accompanied by large federal government stimulus programs, has created demand side inflation. Adding to these pressures, though not the principal cause, are pandemic-driven supply chain disruptions. With inflation outpacing the bank’s forecasts, their interest rate moves have been seen as insufficient.

The bank is reluctant to aggressively increase interest rates since the likelihood of a recession would increase. This would undo the employment effects of the government’s pandemic stimulus measures. It would also add billions of dollars to federal government debt charges, causing a significant impact on their budget spending or deficit target. Given that Canadian households and businesses are some of the most leveraged in the G7, interest rate hikes would hit harder both sectors than those in other G7 countries.

Instead, the Bank of Canada’s intention is to increase interest rates more modestly, and forcefully voice its intention to lower inflation through significantly higher rates – if required. The latter communication strategy is to raise the market’s confidence that the bank will lower inflation. And if the market adjusts its inflationary expectations lower, the bank will subdue inflation and engineer a soft economic landing. This outcome is plausible; though if it does not work, eliminating inflation expectations in the economy later will require even higher interest rates, resulting in greater collateral damage to the economy overall.

About the author

Jerome Gessaroli is a Visiting Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He writes on economic and environmental matters, from a market-based principles perspective. Jerome teaches full-time at the British Columbia Institute of Technology’s School of Business, courses in corporate finance, security analysis, and advanced finance. He was also a visiting lecturer at Simon Fraser University’s Beedie School of Business, teaching into their undergraduate and executive MBA programs.

Jerome is the lead Canadian co-author of four editions of the finance textbook, Financial Management Theory and Practice. He holds a BA in Political Science and an MBA from the Sauder School of Business, both from the University of British Columbia. Prior to teaching, he worked in the securities industry. Jerome also has international business experience, having worked for one of Canada’s largest industrial R&D companies developing overseas business opportunities in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and India.

References

Bank of Canada 2020. Bank of Canada. 2020. “Annual Report 2020.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Annual-Report-2020-Bank-of-Canada.pdf.

Bank of Canada. 2021a. “Monetary Policy Report, January 2021.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/01/mpr-2021-01-20/.

Bank of Canada. 2021b. “Monetary Policy Report, April 2021.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/04/mpr-2021-04-21/.

Bank of Canada. 2021c. “Monetary Policy Report, July 2021.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/07/mpr-2021-07-14/.

Bank of Canada. 2021d. “Monetary Policy Report, October 2021.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/10/mpr-2021-10-27/.

Bank of Canada. 2022a. “Monetary Policy Report, October 2021.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/01/mpr-2022-01-26/.

Bank of Canada. 2022b. “Monetary Policy Report, April 2022,” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2022/04/mpr-2022-04-13/.

Bank of Canada. 2022c. “Interest Rates.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/interest-rates/.

Bank of Canada. 2022d. “Selected Bond Yields.” Bank of Canada. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/interest-rates/canadian-bonds/.

Canada. 2021a. Economic and Fiscal Update 2021. Government of Canada, Annex 1. Available at https://budget.gc.ca/efu-meb/2021/report-rapport/anx1-en.html#economic-projections.

Canada. 2021b. Economic and Fiscal Update 2021. Government of Canada, Annex 2. Available at https://budget.gc.ca/efu-meb/2021/report-rapport/anx2-en.html#adjustments-to-the-2021-22-borrowing-plan.

Canada. 2021c. Fiscal Reference Tables 2021. Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/fin/publications/frt-trf/2021/frt-trf-21-eng.pdf.

Cochrane, John H. 2022. “Fixing Supply Problems Won’t Stop Inflation.” Chicago Booth Review, January 26. Available at https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/fixing-supply-problems-wont-stop-inflation.

Gordon, Julie. 2022. “Bank of Canada turns to interest rate guidance as it battles inflation.” Reuters, May 10. Available at https://www.reuters.com/business/bank-canada-turns-interest-rate-guidance-it-battles-inflation-2022-05-10/.

Hazard, Merle. 2016. “How Long (Will Interest Rates Stay Low).” Track 1 on Tough Market. Available at https://www.merlehazard.com/Songs-and-Videos.html.

Holt, Derek. 2021. “US-Canada Rates Outlook 2021–22: So Long Emergency, Hello Inflation?” Scotiabank, February 12. Available at https://www.scotiabank.com/ca/en/about/economics/economics-publications/post.other-publications.interest-rates.capital-markets–special-reports.us-canada-rates-outlook-2021-22–february-12–2021-.html.

Macklem, Tiff. 2021a. “Monetary Policy Report Press Conference Opening Statement.” Bank of Canada, July 14. Available at. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/07/opening-statement-140721/.

Macklem, Tiff. 2021b. “Monetary Policy Report Press Conference Opening Statement.” Bank of Canada, October 27. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/10/opening-statement-271021/

Macklem, Tiff, 2021c. “Our monetary policy framework: Continuity, clarity and commitment,” Bank of Canada, speech to the Empire Club of Canada, December 15. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/12/monetary-policy-framework-continuity-clarity-and-commitment/.

Mbaye, S., Moreno-Badia, M., and K. Chae. 2018. “Global Debt Database: Methodology and Sources,” IMF Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. Available at https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/GDD.

McSheffrey, Elizabeth. 2022. “BCGEU to hold strike vote for 33,000 public sector employees amid wage impasse,” Global News, May 6. Available at https://globalnews.ca/news/8815463/bcgeu-strike-vote-bc-public-service/.

Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. 2022. “Economic and Fiscal Outlook – March 2022.” Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer. Available at https://distribution-a617274656661637473.pbo-dpb.ca/3b26ede6fae896559139165f58afe8e6bf10ca44163553a90673a2a202748f9b

Pittis, Don. 2022. “New signs of wage inflation may force Bank of Canada’s hand in raising rates,” CBC News, February 3. Available at https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/jobs-wages-parliament-column-don-pittis-1.6334912.

Schembri, Lawrence L. 2021. “Labour market uncertainties and monetary policy.” Bank of Canada, November 16. Available at https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2021/11/labour-market-uncertainties-and-monetary-policy/.

Statistics Canada. 2022. “Canadian Income Survey, 2020.” The Daily, Statistics Canada, March 23.

TD Economics. 2022. “Latest Forecast Tables.” TD Economics. Available at https://economics.td.com/ca-forecast-tables.

Varadarajan, Tunku. 2022. “The Weekend Interview with John H. Cochrane: How Government Spending Fuels Inflation.” Wall Street Journal, February 19.

Wright, Craig, Dawn Desjardins, Nathan Janzen. 2020. “Economic recovery shifts into higher gear.” RBC Economics, June 9. Available at https://thoughtleadership.rbc.com/economic-recovery-shifts-into-higher-gear/?_ga=2.254276680.1358594266.1652416852-1342863623.1650925329.

Appendix 1

Estimating debt charges with higher interest rates

Table 3 shows a forecast of planned new federal bond issues for 2022, along with yield-to-maturities (YTMs) as of May 2022. Assuming the existing planned scenario, all new debts issued in 2022 have interest payments based on the YTMs shown in Table 3. The weighted average YTM is 2.39 percent. 2.39 percent × $453 billion = $10.8 billion in debt charges. If the bank instead raised interest rates to 5.2 percent, which is equivalent to a real rate of 0.5 percent (4.7 percent core inflation + 0.5 percent), total debt charges increase to $23.5 billion (0.052 × $453 billion). The incremental increase in annual debt charges is $12.7 billion ($23.5 billion ‒ $10.8 billion). This estimate is obviously simplified, as it does not account for a number of factors, including maturity risk premiums.

A quick check suggests it is consistent with government figures. Based on government data, new bond issues make up 38 percent of total debt ($453 billion/$1,187 billion). Thirty-eight percent of the government’s forecasted total debt charges is $9.3 billion (38 percent × $24.4 billion) versus the calculated estimate here of $10.8 billion. The difference is likely because of the higher YTMs in May 2022, as used here, rather than the rates used to forecast the earlier government budget estimates.

[1] The core inflation rate is 4.7 percent for March 2022; this number is used by the Bank of Canada. Total inflation, which is widely reported, was 6.7 percent at that time.

[2] Interest rate guidance is not the same “extraordinary forward guidance” which is only used in exceptional circumstances. With extraordinary forward guidance, the central bank explicitly states which conditions must be met before it changes its policy interest rate. For example, in 2020, the Bank of Canada stated its intent to keep its policy rate at 0.25 percent until “economic slack is absorbed and the 2 percent inflation target is sustainably achieved.” See Bank of Canada 2020.