This article originally appeared in the Toronto Star.

By Stephen Buffalo, August 29, 2022

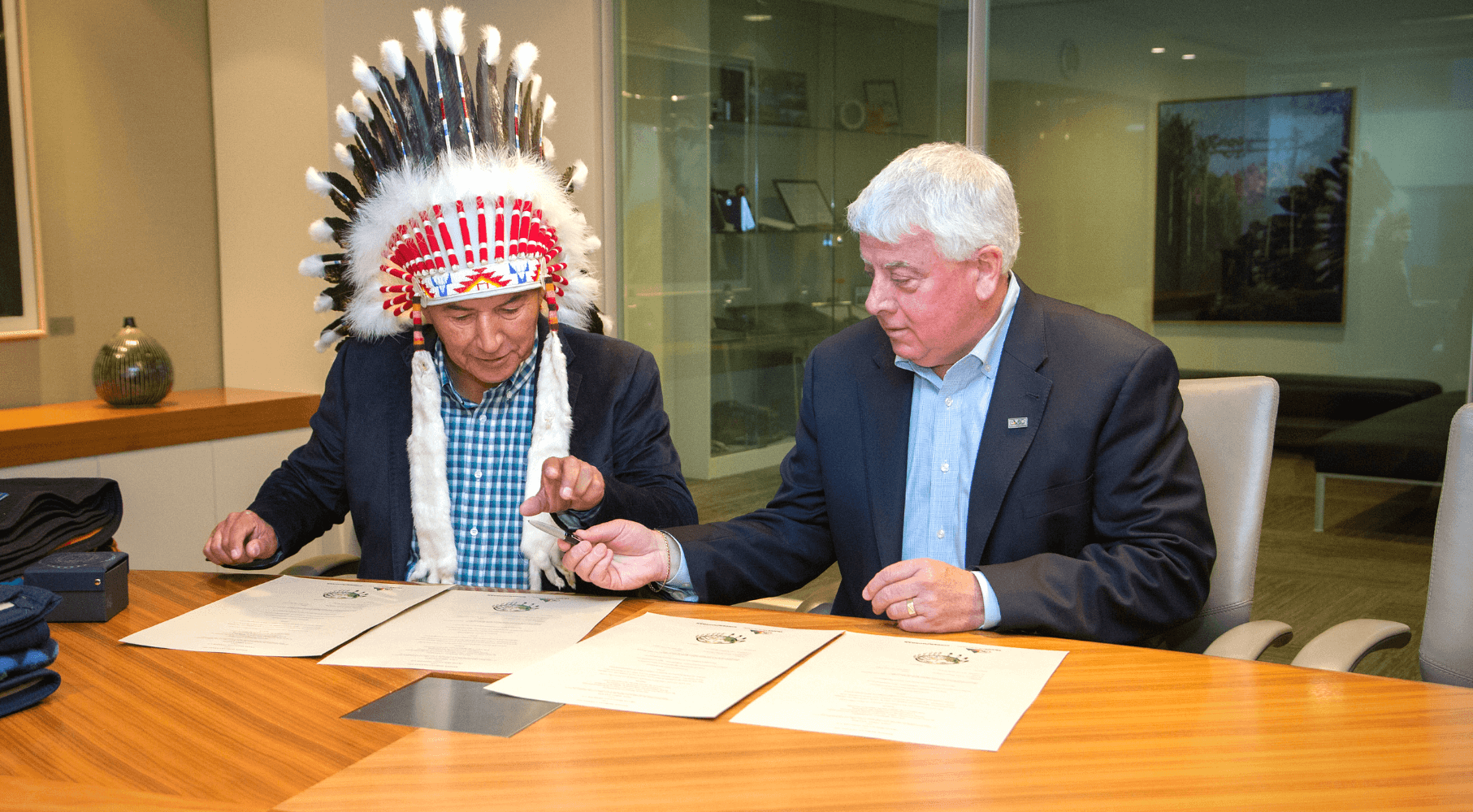

On a recent trip to Bay Street in Toronto, several chiefs and I met with the five big banks, major institutional investors and pension funds to talk about ways they could direct more capital to help First Nations purchase equity in the projects taking place on our traditional territories.

The fact is, First Nations aspire to be more self-determining. We understand better than anyone the toll that imposed dependency on the federal government has taken on our people and communities. The paternalism of the Indian Act, the bureaucracy of Indigenous Services, and the shackles of income assistance have sucked energy out of our cultures and our economies.

Many of us have been working for years to develop alternative revenue sources so that we can make our own decisions without government permission. Like any nation, that means developing our resources and attracting investment to our territories. While our legal rights have been strengthened in recent decades, access to capital remains limited. (The Indian Act ensures that reserve lands are not assets that can be leveraged, but rather held in trust by the Crown.)

What we discussed that day on Bay Street is a win-win strategy: resource projects get access to more capital, investors can pool their risk, and First Nations get stable long-term revenues as well as a real voice at the boardroom table. Building First Nations’ equity into projects also demonstrates informed consent for a project, removing regulatory and legal uncertainty.

Because ESG — environment, social and governance — metrics are already influential in the investment world, we asked our discussion partners to focus on putting the ‘I’ in ESG. Currently, decisions about lending tend to fixate on the ‘E’. This not only reduces the capital that is available to many energy projects with First Nations partners, it pinches the supply of energy that the world needs to meet the basic needs of its eight billion people — including those who live on reserves and are struggling to pay their utilities, buy groceries, or pay for gas.

We already have sustainable lending, and bonds that reward low greenhouse gas emissions. If reconciliation is to be more than a buzzword, we should include Indigenous goals as well.

First and foremost, interest rates can be discounted based on a project’s Indigenous participation: from equity level to Board and executive representation, and from workforce proportion to procurement. This would make resource projects with Indigenous participation more competitive, more profitable, and thus more likely to move ahead.

Similarly, insurance companies could be given incentives to offer a discount on premiums for resource projects that involve Indigenous participation.

Large funds such as the Canadian Pension Plan, which manages half a trillion dollars, could dedicate a portion of its holdings to projects with Indigenous ownership, as it does already with green assets.

The organization I work for, the Indian Resource Council, represents First Nations that produce oil and gas on reserves. Some crude oil marketing firms are proposing that our barrels could attract a slight premium to the market, as a provider of choice. Banks could join this movement through their gas and crude hedging divisions. This kind of thinking would help Indigenous communities prosper by increasing our royalty revenues and attracting investment.

Finally, banks can work with Indigenous communities to develop creative ways to make financing available at reasonable costs, rather than running us through the same template as non-Indigenous businesses and watching us come up short. I know of multibillion-dollar projects with anticipated rates of return of 9 per cent, but where the First Nations partners were offered financing with interest rates of 12 to 15 per cent — worse than a credit card. We can do better than that.

Solving the challenge of Indigenous access to capital will help bring our communities out of poverty, build capacity in our people, and attract investment into resource projects that the world needs. This is not simply a way to make well-meaning investors feel good, as many ESG funds have become. When resource projects have Indigenous ownership and engagement, the regulatory and construction process is going to be faster and smoother, and the outcomes will be better. Indigenous lending is smart money.

Net zero is a worthy goal, but so is Indigenous reconciliation. We have had wealth taken from our territories for more than a century. It’s time for Canada’s investment community to get serious about bringing it back.

Stephen Buffalo is the CEO and president of the Indian Resource Council of Canada, a member of the Samson Cree Nation, and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.