This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Richard Shimooka, June 19, 2024

It has been a dramatic week for the Royal Canadian Navy and the government of Canada. The situation could be straight out of any coming-of-age teen drama as Canada, confident as can be, is cruising around a house party only to stop dead when they see their rival, posted up by the punch bowl, smirking and flirting with the host: “What are they doing here?”

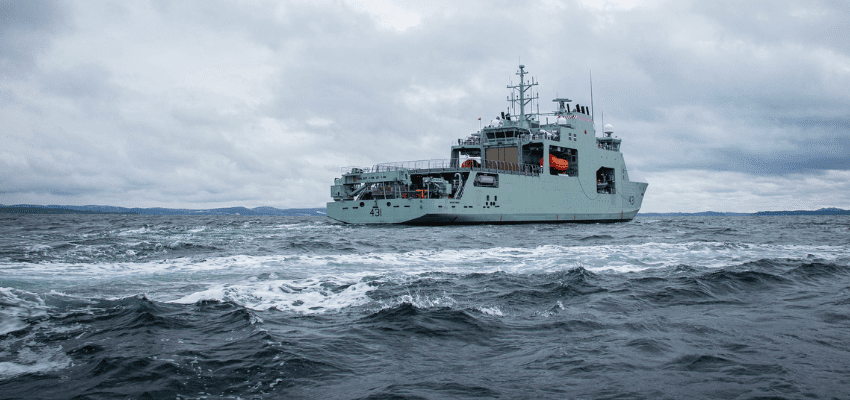

The setting, in this case, is Havana, Cuba, where the RCN’s HMCS Margaret Brooke was participating in a port of call. The arriving rival? Five Russian naval vessels visiting their Caribbean ally. While this may all seem like an overblown coincidence, the entire series of events illustrates some of the strengths of the Canadian military’s capabilities and, more importantly, some of its long-standing weaknesses in policy formation and implementation.

What is a port of call?

For the uninitiated, port visits have come to occupy a critical place in Canada’s diplomatic and security policy over the past decade. While they have a very long tradition, since 2015 the government has made a significant effort to use them to cultivate diplomatic relations with states, particularly in the Indo-Pacific. During a visit, the local ambassador and Global Affairs Canada (GAC) in Ottawa will organize events around the ship. This includes hosting delegations and meetings on the vessel, arranging shore visits, and engaging in humanitarian activities.

Planning a port visit usually occurs months before a vessel departs for a deployment as they require an extensive inter-departmental process. A request to undertake a port visit to Havana, given its sensitivities, would almost certainly come from GAC and/or the prime minister’s office. In these cases, they should be viewed more as a very high-level diplomatic event, with the PMO and the minister of foreign affairs directly involved. From here, the military starts studying the requests’ feasibility as naval vessels tend to have packed itineraries over a deployment—there are exercises with allies, temporary secondment to ongoing multilateral operations, and other port visits that all pull on a schedule.

In this case, it is highly unlikely that the idea would have originated from within the Department of National Defence. Cuba is not an ally, and there are very limited military benefits that would be accrued from a port visit. They are particularly troublesome for crews, requiring a number of additional measures to secure the vessels and personnel in port, as well as extensive diplomatic negotiations. These considerations are part of the reason why visits to Cuba occur relatively infrequently.

Understanding the policy effort involved, it is very unlikely that the government of Canada scheduled the Havana port visit to coincide with the Russian squadron’s arrival. The most reasonable explanation is it was, for Canada, an unlucky coincidence, given that the HMCS Margaret Brooke’s visit was planned in the months before April when the ship left port, yet the Russian deployment was only officially announced on June 6th, when the squadron departed Severomorsk in the Russian high Arctic.

Does this let the government off the hook? Not necessarily. It is almost assured that Western intelligence-gathering efforts would have known that such a deployment was in the offing, perhaps several weeks in advance.

Russian visits to the Caribbean are not an uncommon occurrence; since 2008 its vessels have visited the region at least a half dozen times, coming to Havana and Russia’s other close ally, Venezuela. Once deployed they tend to participate in exercises and drills to improve their capability to operate in the region with allies.

This case is different in two respects. The clearest one being that the squadron was accompanied by a Yasen-Class SSGN, the Kazan, one of Russia’s most advanced submarines and a notable leap in capabilities compared to earlier visits. Second, the visit’s announcement came a day after President Putin stated that the Russian Federation would take asymmetrical steps to counter increased U.S. support of Ukraine, including supplying arms to groups in conflict with them. This visit was clearly a case of Putin flexing his muscles in America’s backyard.

Canada’s response

The optics are not good for Canada, and what it says about the capabilities of Canadian political planning and leadership is even worse.

Ottawa’s initial response to the Russian deployment was measured and effective. As the Russian squadron neared Canada’s exclusive economic zone, it was shadowed by the HMCS Ville De Quebec along with the USS Truxton and U.S. Coast Guard cutter USCGS Stone, as well as CP-140 maritime patrol aircraft. The Ville de Quebec’s participation is noteworthy as the vessel is the first of the class to receive the Underwater Warfare Suite Upgrade—a new set of systems that allows the vessel to better detect and track submarines and surface vessels. Shadowing the Russian vessels then is certainly an important intelligence-gathering opportunity. Gleaning data on their electronic emissions and acoustics, especially for relatively new vessels like the Admiral Gorshkov and Yasen classes, is very useful for Canada and allies’ defence planning.

All that being said, these benefits have not outweighed the harm done by the now clearly problematic port visit. Most glaringly, the episode is indicative of a long-standing issue with Canadian foreign and defence policy that has been apparent over the past thirty years: the lack of a true interdepartmental national security apparatus that is able to effectively implement and manage foreign policy. Canadian governments have generally reacted to crises ineptly, often pursuing inconsistent policy positions that undermine overall objectives.

On its own, a port visit to Cuba is not necessarily a problem. As noted earlier, maintaining cordial relations with an adversary has benefits, and a visit every eight years should not be seen as a major policy departure.

In this case, however, once the Russians showed up, continuing the port of call undermined Canada’s strong support for Ukraine, especially given that this incident occurred right on the heels of the G7 meeting and Switzerland peace summit. Cuba is a strong supporter of Russia in the Ukrainian war, largely mirroring the latter’s point of view on Western aggression and the need for the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine. Its official state-run newspaper dismissed the Swiss summit as effectively a ploy to continue imperialist aggressions against Russia. Providing them the prestige of a port visit with the HMCS Margaret Brooke in the same harbour as Russian vessels could be trumpeted as a tacit acceptance of Cuba’s support for its Russian ally in this conflict.

Other explanations, like the one made by Minister of National Defence Bill Blair that the visit was intended to “deter” Russia, are patently ridiculous when Cuba is a close ally to Moscow and even hosts a major Russian intelligence collection facility on their territory. The optics of a G7-nation vessel sharing an anchorage with Russian vessels is an unequivocal political win for the Russian side and again brings into question the government’s overall judgment on this matter.

And not just internationally. Domestically, the optics are perhaps even worse. This incident comes after several weeks of news on foreign election interference where the government’s lacklustre response to that overall threat—potentially including meddling by Russia—has undermined confidence in Canada’s democratic systems.

What Canada should have done

What should have occurred was for a senior government official to convene a meeting with senior bureaucrats and political representatives and weigh the port of call’s benefit against the much more important support for Ukraine and hemispheric security. Any rational assessment would have spotted the mismatch.

Yet it is unclear whether this happened. Speaking on CBC’s Power and Politics, Minister of Foreign Affairs Melanie Joly said she had not heard about the situation when prompted by the host to comment. If we take her comments at face value, then that is the clearest possible evidence of a failure in the interdepartmental policy process. Yet her surprise is questionable given how, as mentioned, deeply involved GAC would have been in pushing for and planning the HMCS Margaret Brooke’s port visit.

The correct course of action would have been to send an unequivocal and strong message: cancel the port of call as soon as the Russian port visit was known about.

Certainly, a last-minute scrub of the visit would have elicited negative reactions from Havana, but there are benefits to that. It would clearly signal to the ruling party that its position on Ukraine is unacceptable to Canada, as is hosting a Russian deployment that was clearly intended to provoke the United States and deteriorate regional security. This would have much better served Canada’s overall interests and avoided the poor optics and marginal benefits that the port visit accrued.

In the end, this event will blow over and there are not likely to be any lasting marks on Canada’s reputation. But it is just another unforced error that illustrates all too clearly the government’s inability to craft and implement an effective foreign policy for the much more dangerous age in which we live.

Richard Shimooka is a Hub contributing writer and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who writes on defence policy.