This article originally appeared in The Hub.

By Trevor Tombe, December 12, 2024

As the possibility of a broad-based U.S. tariff on Canadian goods grows, many—including myself recently for The Hub—have understandably focused on the big-picture economic hit.

In recent work with the Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s Business Data Lab, I found a 25 percent across-the-board tariff by the United States could shrink Canada’s economy by 2 to 3 percent—depending on if, and how, we retaliate.

But focusing only on GDP risks overlooking the most personal dimension of all: jobs.

So, how many positions could be disrupted by a broad U.S. tariff?

Some little-known (but incredibly valuable!) data and analysis from Statistics Canada can shed light on this question.

How many jobs might be affected?

We don’t need a model of Canada’s economy to simulate the effect of a tariff to appreciate the potential scale of disruption that might occur. The raw data itself presents a stark enough picture.

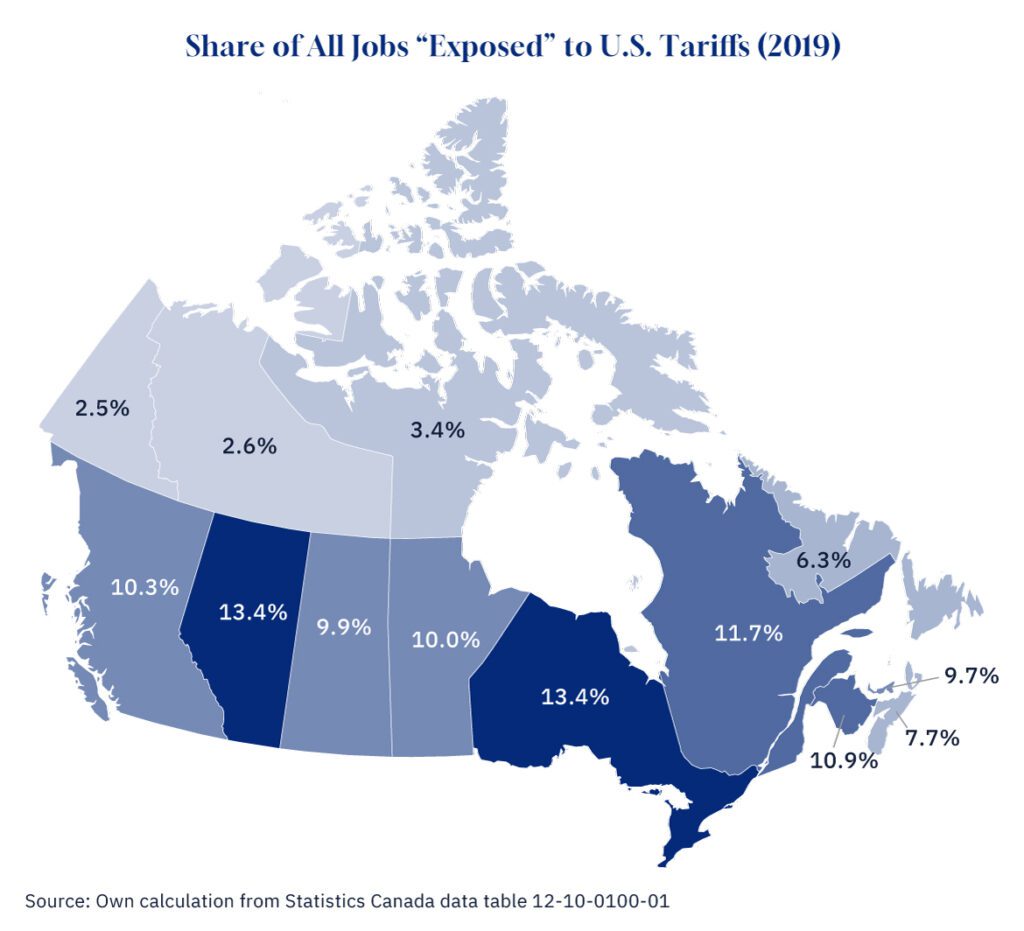

In total, I estimate that approximately 2.4 million Canadian jobs are exposed to U.S. tariffs. That’s about one in seven jobs in Ontario and Alberta at the high end, to a low of one in 16 in Newfoundland and Labrador, with other provinces falling somewhere in between.

Of course, “exposed” doesn’t mean all these 2.4 million jobs would vanish overnight following a 25 percent U.S. tariff. Not at all. Most will almost certainly remain, though potentially with reduced hours, lower pay, or, at the very least, heightened uncertainty.

Disruptions to national supply chains

We also need to consider the diverse range of products and sectors that would be affected.

In Prince Edward Island, over half of all U.S. exports last year were potatoes, totaling roughly $800 million. In Nova Scotia, tires topped the list with $1.2 billion, surpassing seafood’s impressive $1 billion. Meanwhile, New Brunswick sent $11 billion worth of fuels south, and Quebec sent $10 billion in aluminum shipments. Add in Ontario’s $71 billion in automotive exports and Manitoba’s mix of pharmaceuticals, machinery, and food products, and it’s clear that no single region or sector looks the same.

This complexity matters for jobs at risk of a tariff disruption. A tariff that squeezes potato or tire exports puts pressure on vast supplier networks, potentially causing shockwaves nationwide.

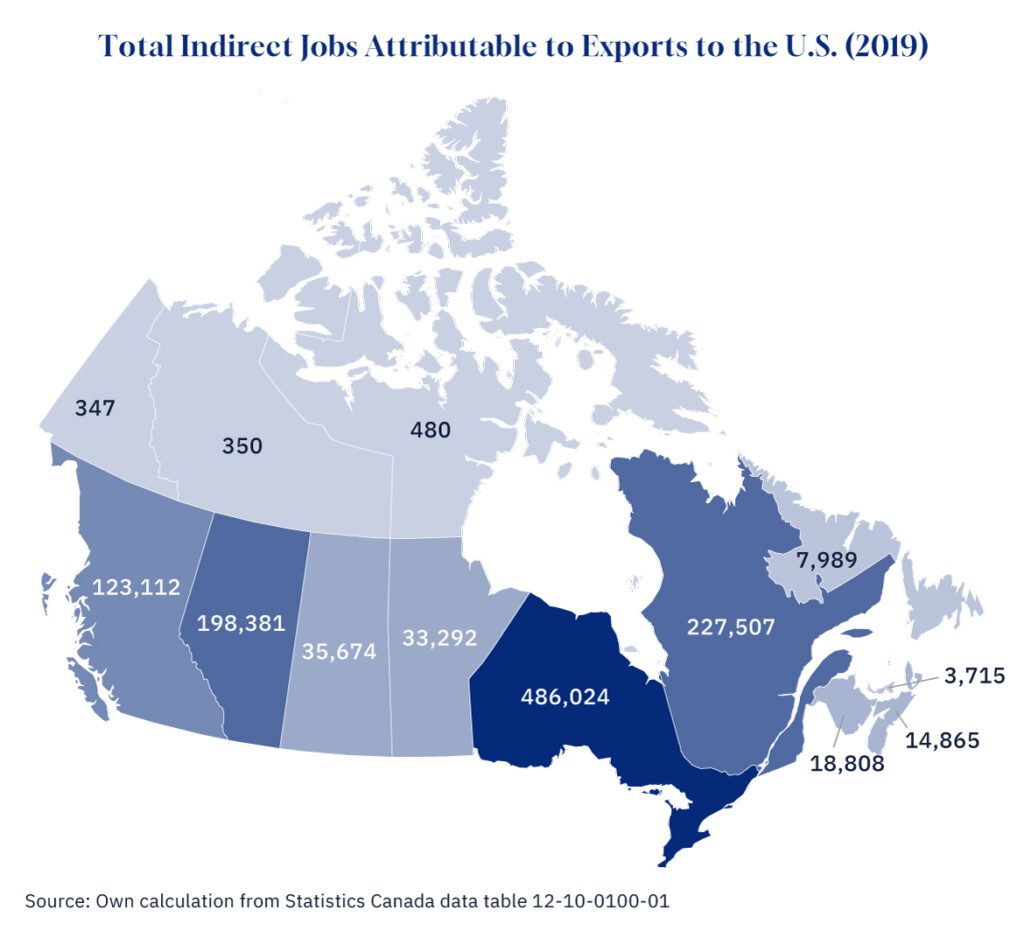

I estimate that only about half of Canada’s tariff-exposed jobs are employed by the exporting companies themselves. The other half—approximately 1.2 million jobs—belong to suppliers and service providers who don’t export directly but still depend on that cross-border demand.

That’s 6 percent of all jobs in Canada. And from half a million in Ontario to a quarter million in Quebec to almost 200,000 in Alberta, these indirect jobs exposed to U.S. tariffs also span the country.

Even more striking is the interprovincial nature of these connections. I estimate over 300,000 Canadian jobs support an exporter in another province—meaning one region’s tariff troubles can spill into another’s job market. Depending on the province, this accounts for 1 to 3e percent of all jobs. That’s huge.

How much of our income is tied to U.S. exports?

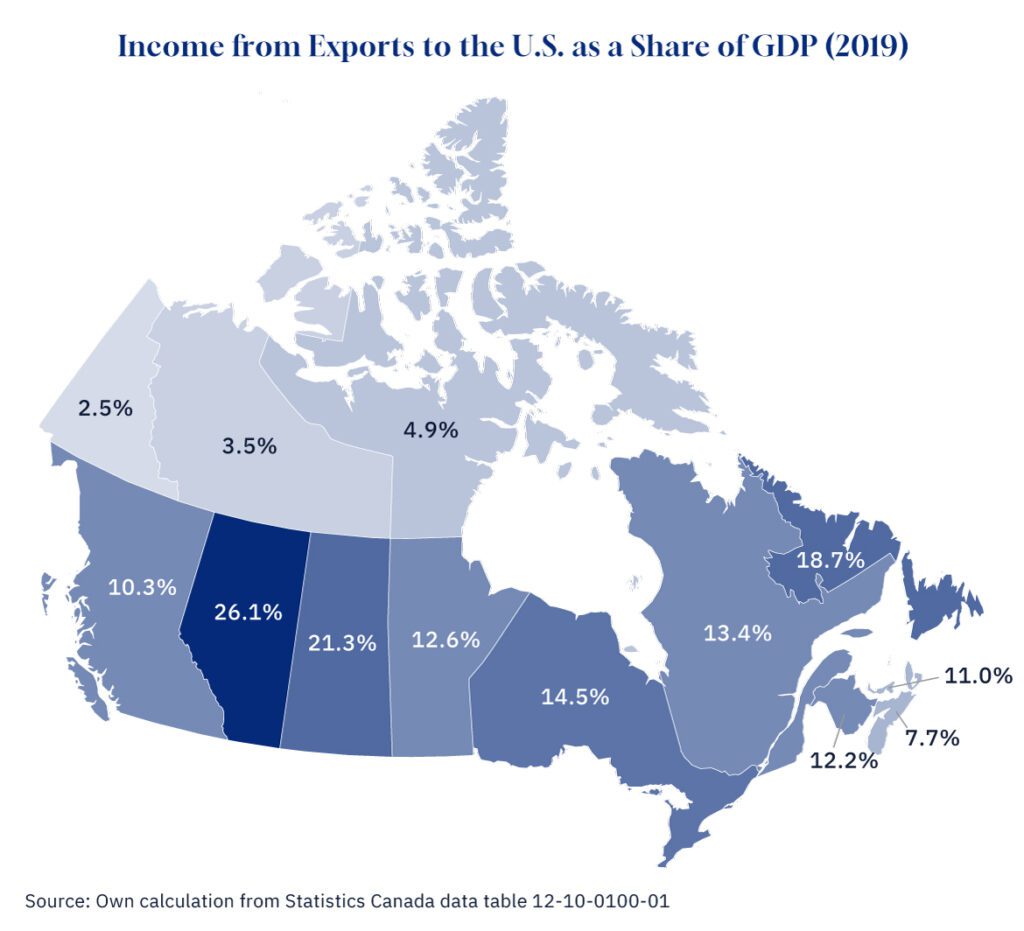

Of course, employment is only one piece of the puzzle. Income earned by workers and business owners is another. And to get at this, we can’t just add up the total value of exports.

A dollar in exports, after all, does not necessarily translate into a dollar of income earned by a Canadian. There are parts and other inputs that go into the exported final good, and the income generated by producing those inputs might not be located in Canada at all.

Indeed, nearly $55 billion worth of Ontario’s exports to the United States was actually accounted for by imported inputs from the United States. Combined with income earned by suppliers elsewhere in Canada (or elsewhere around the world, for that matter), I find that Ontario’s nearly $200 billion in U.S. exports (in 2019) generated less than $110 billion in income for the province. Of course, some of the exports by other Canadian provinces add to Ontario’s income too.

Accounting for all this, I find about 14.5 percent of Ontario’s total GDP is from income earned off exports to the U.S. That’s a lot, to be sure, but it’s not the highest share.

Alberta leads the pack at over one-quarter of each dollar earned coming from exports to the U.S. By this measure, it is the most exposed province to tariff disruptions by a wide margin. And of that, roughly 2.5 percent of income earned is from another province’s exports to the U.S.—among the highest shares of any province and fully one point higher than Ontario’s 1.5 percent.

Understanding all of these complicated spillovers from Canada-U.S. trade is essential if we want to cushion against the worst impacts of potential American tariffs.

Even if tariffs target only a single industry, the effects can ripple through supply chains and job markets nationwide. That’s why a “Team Canada” perspective matters—what happens in one region can affect every corner of the country.