By Lawrence Herman, December 13, 2022

“Friend-shoring,” “near-shoring” and the related though elastic concept of “supply chain resilience,” are all part of the same piece, aimed at reconfiguring supply chains to protect national interests. The following article looks more closely at these concepts in light of the current global trading environment.

What do we mean?

The terms are used frequently these days, including in the Canadian government’s recently released Critical Minerals Strategy (Canada 2022b, 35) as well as its Indo-Pacific Strategy (Canada 2022a, 18).[1] In the current global context, it means, in large part, de-coupling from China, especially in high-tech manufacturing, related services, artificial intelligence (AI) and other sensitive intellectual property fields.

While the idea of friend-shoring has been percolating for a while, in a May 2022 speech in Brussels, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen talked about supply chain arrangements – friend-shoring – with “trusted countries.” As he goes on to say:

Favoring the friend-shoring of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries, so we can continue to securely extend market access, will lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners. (Atlantic Council 2022)

She went on to cite Russia and China, little wonder, the latter being a major competitor in rare earths used in aviation, vehicle production, battery manufacturing, renewable energy systems and technology manufacturing.

Finance Minster Chrystia Freeland said much the same in an October 2022 speech at the Brookings Institution. Friend-shoring, she said:

can make our economies more resilient, our supply chains true to our most deeply held principles, and protect our workers and the social safety net they depend on from unfair competition created by coercive societies and race-to-the-bottom business practices.

. . . if we are to tie our economies even more closely together, we must be confident that we will all follow the rules in our trade with each other, even and especially when it would be easier not to. We will friendshore more quickly and effectively if we work together to develop shared approaches, and if we make an explicit commitment to each other to implement them. (Freeland 2022)

Freeland said that democracies must make a conscious effort to build supply chains through each other’s economies, meaning countries with shared democratic values. While this suggests some form of intergovernmental friend-shoring agreement among like-minded countries, neither Yellen nor Freeland went quite that far.

With China in the background, supply chain resilience has been discussed in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development for the last few years (OECD Undated), as well as in other forums. China is the motivation for the US-led Supply Chain Ministerial Forum, a group of like-minded countries meeting to exchange ideas (US Department of State 2022). But given the politics and legal complexities, there’s no real likelihood of agreement or arrangement among governments emerging from these exercises.

For one thing, it would take endless time and enormous political capital to reach any kind of friend-shoring deal, even among friends and allies. Any such initiatives could also run up against the World Trade Organization and other trade agreement strictures forbidding discriminatory measures favouring domestic suppliers over foreign producers. Finally, other methods can be employed to achieve a good number of friend-shoring objectives in the absence any international agreement. These are discussed below.

Advances

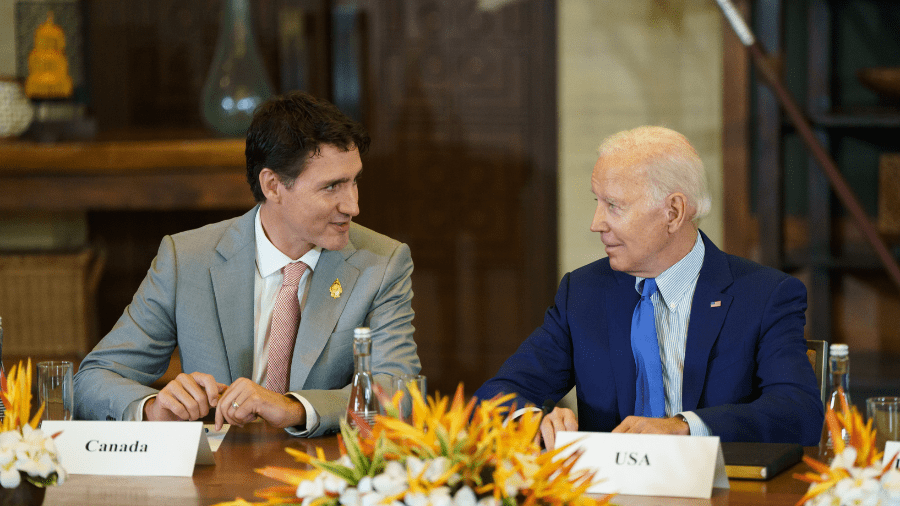

The bilateral Canada-US front shows prospects for at least some kind of policy alignment and even informal arrangements on re-shoring, part of the Biden-Trudeau declaration of February 2021 for a “Roadmap for a Renewed Canada-US Partnership.” This has led to two initiatives, the Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals (Canada 2020) and the Canada-US Supply Chain Working Group (Canada 2021) which, together with Canadian discussions with the European Union (EU) and Japan, are part of the December 2022 Critical Minerals Strategy referred to earlier.

While these discussions are going on, other elements have led to significant commercial disengagement with Russia and Iran, and now to partial de-coupling from China, which amount to supply line reconfiguration and a kind of friend-shoring at the corporate level.

Sanctions and export controls

First, China’s aggressiveness, Russia’s war in Ukraine and actions of bad actors such as Iran, have resulted in national security becoming a front burner issue for western allies. These countries and their companies. businesses, government entities and identified individuals persons are subject to a complex set of westen sanctions, led by the United States, with the EU in second command, typically followed by others in close formation, including Canada.

Because of wide geographic and sectoral scope, especially in regard to American measures impacting banking and financial transactions, sanctions have forced extensive supply chain reconfiguration, including moving away from sourcing goods or services from China.

A second element in supply line reconfiguration is the expansion of export controls by western governments. These differ from sanctions in that they are prospective and strategic, as opposed to sanctions being reactive and tactical.

There’s a history to these controls. Long-standing intergovernmental agreements among supplier countries require governments to control exports of nuclear goods and technology, weapons of mass destruction and an array of dual-use items. On the unilateral front, there’s the recent and expansive US Commerce Depart Rule that controls direct and indirect exports on semiconductors with any American content – both goods and related technology – to China.[2]

The effect of sanctions and export control systems is that supply chains are being recalibrated, resulting in a large degree of re-shoring and friend-shoring in the absence of any kind of agreement among like-minded allies.

Private sector “rule-making”

Supply chains are series – often a complex series – of interrelated purchase and distribution arrangements plus related financings. Supply chain re-arrangements will only work if the business sector changes these commercial arrangements. This is happening now. While governments exchange ideas on supply chain resiliency, the private sector has often acted on its own without treaties or laws mandating action (Herman 2021). Businesses have adopted policies and standards for re-shoring and friend-shoring independent of laws, regulations or governmental policies.

Private sector rule-making, as its often called, actually started about 20 years ago, with voluntary standards of corporate social responsibility (“CSR”), then morphed and expanded into the matrix of today’s environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) standards.

These have not resulted from corporate generosity and altruism but rather from investor and social pressure, such as public opprobrium in doing business with regimes like Russia or China, which are guilty of an array of human rights abuses. Whatever the motivation, the fact is that private sector rules, practices and standards – private, non-binding governance – are an indelible feature of international business.

The challenge is for like-minded countries to agree to facilitate these kinds of voluntary rules and make it easier for business to enter into friend-shoring arrangements among a mix of suppliers, distributors and end-users within the framework of public policy. That includes policies that encourage a move away from countries like China, Russia and Iran that threaten the public interest.

The subsidization spectre

Yellen spoke about “incentivizing” friend-shoring. Freeland talked about designing government procurement and “incentive programs.” This raises concerns over subsidization of friend-shoring transactions, a highly fraught issue, particularly in regard to US policy and the massive financial resources and incentives committed to green energy projects under the Inflation Reduction Act (Rauhala and Nakashima 2022).

It’s not clear how friendly or trusted allies, including Canada, will deal with the subsidy issue.[3] While Canada and the US have agreed that IRA tax credits will be available for all electric vehicles (EVs) qualifying under North American content rules under the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), other subsidies and credits in the measure could have serious impacts on Canada.

The result is that while formal friend-shoring agreements are out of the question, there has to be some kind of understanding about the use of both domestic and export subsidies and agreement on those subsidies that are permitted to enhance friend-shoring operations. Otherwise, the bold idea of some kind of coordination of supply chain reconfiguration among allies as voiced by Yellen and Freeland will come to naught.

The way ahead

It’s a fraught world, with the pre-existing global order shattered and geopolitical relations unended by the ascendency and commercial aggressiveness of China, with another major blow to international trading order caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Added to this are unsettling events elsewhere, notably in Iran.

In response, there has been a corresponding de-coupling of commercial dealings with these countries, impelled by Western sanctions and export controls sanctions and export controls. These have become firmly embedded in the international trading system and will be with us for decades to come. That is the reality of today’s destabilized state of international trade. The effect has been re-shoring and friend-shoring, as supply chains are reconfigured.

The prospects for any kind of intergovernmental friend-shoring agreement, however, is unrealistic. What leaders in the West, such as Janet Yellen, Chrystia Freeland and others have talked about is possibly an informal network among western governments, some of which has been augmented by notable private sector voluntary action in supply chain adjustments.

While this is happening, the spectre of state subsidies exists, led by recent developments in the United States. Unless some kind of accommodation is reached, national subsidies could pose difficulties for even informal coordination of supply chain adjustments. Friend-shoring arrangements, even if talked about optimistically in some quarters, could prove to be short-lived.

Lawrence L. Herman is international trade counsel at Herman & Associates and Senior Fellow of the C .D. Howe Institute, Toronto.

References

Atlantic Council. 2022. “Transcript: US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen on the next steps for Russia sanctions and ‘friend-shoring’ supply chains.” Atlantic Council, April 13. Available at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/news/transcripts/transcript-us-treasury-secretary-janet-yellen-on-the-next-steps-for-russia-sanctions-and-friend-shoring-supply-chains/.

Canada. 2020. “Canada and U.S. Finalize Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration.” News Release. Natural Resource Canada, January 9. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2020/01/canada-and-us-finalize-joint-action-plan-on-critical-minerals-collaboration.html.

Canada. 2021. “U.S.-Canada/Canada-U.S. Supply Chains Progress Report.” Government of Canada, November 18. Available at https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/supply_chains_progress_report-rapport_etape_chaine_approvisionnement.aspx?lang=eng.

Canada. 2022a. Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. Government of Canada. Available at https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/indo-pacific-indo-pacifique/index.aspx?lang=eng.

Canada. 2022b. The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy. Government of Canada. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/campaign/critical-minerals-in-canada/canadian-critical-minerals-strategy.html.

Freeland, Chrystia. 2022. “Remarks by the Deputy Prime Minister at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.” Government of Canada, October 11. Available at https://deputypm.canada.ca/en/news/speeches/2022/10/11/remarks-deputy-prime-minister-brookings-institution-washington-dc.

Herman, Lawrence. 2021. “Reshoring initiative targets behaviors, not laws.” Globe and Mail, April 12. Available at https://www.cdhowe.org/expert-op-eds/reshoring-initiative-targets-behaviours-not-laws-globe-and-mail-op-ed.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD]. Undated. “Keys to resilient supply chains.” OECD. Available at https://www.oecd.org/trade/resilient-supply-chains/.

Rauhala, Emily and Ellen Nakashima. 2022. “European officials object to Biden’s green subsidies as protectionist.” Washington Post, December 4. Available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/04/america-first-ira-biden-eu/.

United States Department of State. 2022. “U.S. Convenes Supply Chain Ministerial Forum.” Fact Sheet, Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs, US Department of State, July 19. Available at https://www.state.gov/u-s-convenes-supply-chain-ministerial-forum/.

[1] The Critical Minerals Strategy says that it will be aligned with its Indo-Pacific Strategy. The two are linked in this way.

[2] On October 7, 2022, the US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (“BIS”) issued rules aimed at restricting China’s ability to obtain advanced computing chips, develop and maintain supercomputers, and manufacture advanced semiconductors (87 FR 62186),

[3] “In Brussels, the de facto E.U. capital, diplomats are assessing different points of leverage, including potentially using the Biden administration’s desire to coordinate on China strategy, to press their points. . . . There has also been talk in Brussels of raising the issue at the World Trade Organization. While few have the appetite for a trade war, some feel such an extreme recourse may be necessary if the U.S. side presses ahead.” See Rauhala and Nakashima (2022).