By Dylan R. Clarke

February 11, 2026

Court delay is not a new problem – but in recent years, it has taken on a new urgency in Canada. Since the Supreme Court’s 2016 decision in R. v. Jordan [Jordan], roughly 10,000 cases each year have been stayed because they took too long to reach completion (Ebner 2025).

Jordan imposed firm time limits – 18 months for cases in provincial court and 30 months for cases in superior court – from charge to resolution. At the time of the decision, critics were skeptical that a fixed ceiling was the right path forward given the complete absence of evidence behind the selected limits of 18 and 30 months.

The Supreme Court’s goal was clear: to force a complacent legal system marked by growing delays and spiralling populations in pre-trial custody to finally take the right to a timely trial seriously. However, the means were controversial from the outset. The Court selected these timelines without strong evidentiary foundation, betting that clear and hard rules would succeed where decades of exhortation had failed.

Nearly a decade later, that bet looks increasingly uneasy. Courts have struggled to reconcile Jordan‘s rigid ceilings with the realities of crowded dockets, uneven resources, and local variation. As a result, judges are turning more often to Jordan’s narrow “exceptional circumstances” carve-out – an approach now under scrutiny in R v. Vrbanic, a case before the Supreme Court of Canada. This judicial improvisation raises a deeper question: whether courts are being asked to solve a structural problem that may better be addressed by legislatures, with their capacity to consult experts, tailor responses to local conditions, and invest in system-wide reform.

Court congestion is among society’s oldest legal problems; protections from it are enshrined in constitutions around the world. We are told that in 42 AD the Emperor Claudius exhorted the Roman Senate to pass a law introducing a summer session into the congested Roman courts (Kalven Jr. 1963); in 1215, King John promised in the Magna Carta that “to no one will we deny or delay, right or justice”; around 1600, Shakespeare’s Hamlet lists “law’s delay” (3.1) fifth in his seven burdens of man; Kafka’s early 20th-century critique on Austro-Hungarian criminal procedure, The Trial, makes immediate mention of the phenomenon; in 1971, William Landes wrote in The Journal of Law and Economics that “[i]t is widely recognized that the courts are burdened with a larger volume of cases than they can efficiently handle” (p. 74). The list goes on. Indeed, the right to trial within reasonable time is enshrined in the Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution under the Speedy Trial Clause and in section 11(b) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

When justice is delayed, we deny the constitutional rights of the accused, who are presumed to be innocent but often held in pre-trial custody or under restrictive bail conditions. The costs of delay impose a substantial burden on the lives of those who interact with the criminal justice system.

Canada’s Charter protects the accused’s security, liberty, and fair trial interests by preventing trials or bail from lingering indefinitely and by ensuring proceedings occur while witnesses and evidence are available. These guarantees mitigate the undue costs of prolonged detention in pre-trial custody, such as failure to meet employment and housing obligations, deterioration of personal relationships, as well as the ability to prepare a defence. Prolonged delay can result from inadequate administrative resources, underscoring the need for constitutional protections to ensure swift justice.

While trial delay is a long-standing problem, it remains among the most pressing legal challenges today. In Canada, it has taken on renewed constitutional significance, making the issue particularly timely. In Jordan, the Court sought to bring in predictability to litigation under the right to be tried within reasonable time by establishing presumptive ceilings of 18 months from charge to disposition, extendable to 30 months for cases in superior court (or provincial court cases following a preliminary inquiry). The Court expressly acknowledged an underlying pathology of sluggishness in the administration of justice, with the majority opinion writing:

[w]hile this Court has always recognized the importance of the right to a trial within a reasonable time, in our view, developments since [R. v. Morin (1992)] demonstrate that the system has lost its way. The framework set out Morin has given rise to both doctrinal and practical problems, contributing to a culture of delay and complacency towards it (para. 29)

The Court went on to write that “[t]he first step in determining whether Mr. Jordan’s s. 11(b) right was infringed is to determine the total delay between the charges and the end of trial” (para. 119). The Court then set presumptive ceilings of 18 and 30 months, after subtracting defence delay and discrete events, beyond which the right under s. 11(b) is presumptively violated. The Court quickly offered avenues for rebutting presumptively unreasonable delays above the ceilings with either discrete events or particularly complex cases in 2017 in R. v. Cody [Cody]. The Ontario Court of Appeal then had to again clarify the amount of time required for sentencing in R. v. Charley in 2019. In doing so, the Court ultimately offered a much clearer interpretation of s. 11(b) that will make for much more predictable constitutional litigation in the future, but the shift has incurred growing pains.

However, the concurring opinion by Cromwell J. in Jordan expressed skepticism that the framework established by the majority in 2016 is the right path forward for the law. The ceilings chosen by the majority’s framework have no basis grounded in the particulars of a given case but for a preliminary hearing, nor do they stem from any form of statistical analysis of the empirical duration of criminal cases. The duration of criminal trials emerges from a series of factors specific to the case at hand, not just inadequate resources. While the majority’s framework allows for some of these factors, such as defence delay and discrete events, it may be too rigid a framework. The Court offered a release valve for Jordan‘s strictness in rare and exceptional circumstances, emphasized by the Court in Cody, but these are poised to become more of the rule than the exception that they were intended to be.

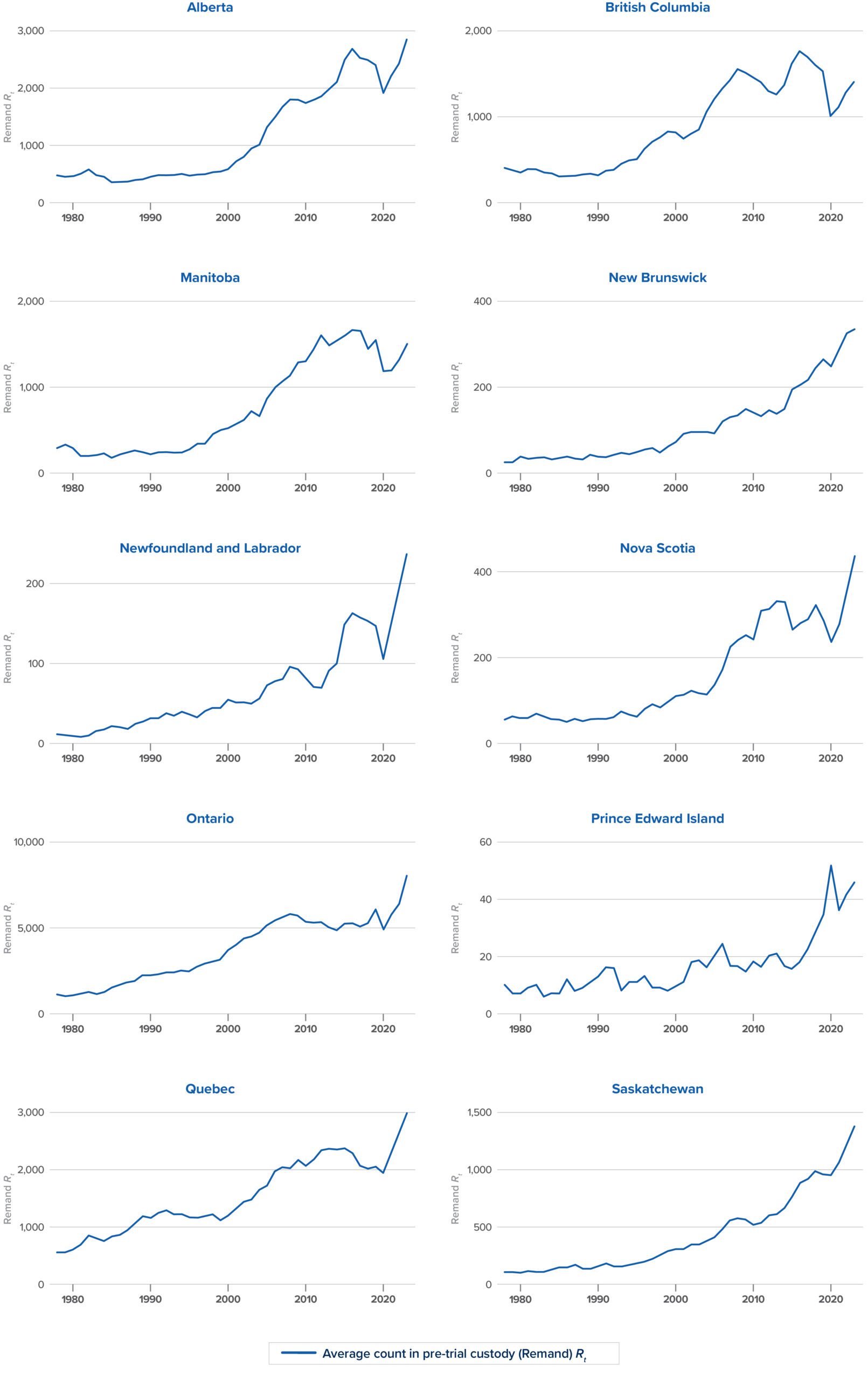

Ten years into the post-Jordan era, the concurring opinion of Cromwell J. has rung true in arguing that “creating these types of ceilings is a task better left to legislation” (para. 147) and thereby “informed by facts” (para. 293). Little is known about the extent to which the Court’s framework in Jordan reined in the so-called “culture of complacency” or if the criminal justice system continues to spiral out of control. A formal empirical examination is clearly required. The data displayed in Figure 1 conveys a troubling trend for the population in pre-trial custody (remand) across many provinces from 1978 to 2024. Research conducted by Clarke and Metzler (2025) shows that court congestion is a major problem. Using queueing theory, the authors find that the criminal justice system appears to be spiralling out of control, and that court congestion can resolve the paradox of the secular rise of the population in pre-trial custody with falling crime rates. To be sure, there is a congestion problem that Jordan attempted to fix.

Figure 1: Average counts of adults in provincial and territorial correctional programs

Populations in pre-trial custody continue to grow after being emptied during the pandemic. Serious offences with harmed victims go unpunished. The Court’s majority decision in Jordan attempts to stand up for our most basic constitutional liberties and incentivize state actors, but it may have just offloaded the problem to victims and society. We live in an obscure point in history where the Supreme Court of Canada in 2016 decided that it knew how long criminal trials across the country in every category of offence were going to take: 18 or 30 months. They were evidently wrong.

But we’ve seen this all before. The Court made the same error in R. v. Askov, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 1199 that it had to rapidly self-correct in Morin (Baar 1997), which was the prevailing framework up until Jordan. The Court in Askov held that 34 months to bring a case to trial was prima facie excessive. More than 700 days had elapsed from the time the case was first spoken to in the district court, and none of the delay could be attributed to the prosecution or the defence. A misinterpretation of Justice Cory’s language in Askov at p. 1240 led trial judges and provincial governments to assume that the Court’s unanimous judgment meant a six-to-eight-month standard for criminal cases. Justice Cory himself apologized publicly. The Court quickly reversed its decision two years later given the opportunity in Morin.

Six, 8, 18, 30 – none of these numbers have any special constitutional significance. What clearly did change – by a wide margin – between 1990 and 2016 was the definition of an “unconstitutionally lengthy” delay. Rather, as Scalia so aptly phrased the task of judicial policymaking, these ceilings appear to be drawn from “the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie.” The Court is clearly at the point where it is making public policy from the bench rather than performing its role in judicially reviewing acts of Parliament or executive action. The Court in Jordan attempted to shape incentive structures around the culture of complacency by setting out clear presumptive ceilings for unreasonable trial delay. However, Parliament and the Attorney General have evidently not properly responded to the Court’s demands set out in Jordan given the imminent wave of litigation on the right – a simple CanLII search of “s. 11(b)” from 2016 to present yields nearly three thousand results, the most of any legal right of the accused within s. 11 of the Charter.

The future of trial delay policy

While the impact in 2016 may not have been of the same magnitude as it was in 1990, the problem of fixed ceilings remains the same. The Court is policymaking from the bench, perhaps not because it wants to, but because it must. It is worth considering what the proper future of the right to trial within reasonable time looks like if we could simply scrap the judicial history and start all over again. The contextual US approach in Barker v. Wingo is precisely what Jordan attempted to move away from to address a culture of complacency, but some US states have legislated on top of that constitutional direction.

A more nuanced approach to the right to trial within reasonable time is needed, but the Court is not the most appropriate body to provide it. The separation of powers suggests Parliament or the provincial legislatures, and not the Court, are the best fit to deal with complex, polycentric issues. The Court can set hard limits to incentivize the State, but it lacks the expertise to decide whether a strict ceiling or some other constitutional limitation is most appropriate. The section 11(b) of the future should move toward judicial review of legislation on the matter and stop short-circuiting democracy with judicial policymaking.

Bill C-16 (the Protecting Victims Act) attempts to legislate discretion back into the rigid Jordan framework.

It would:

create a new Part in respect of unreasonable delay that requires a court to consider specific factors in relation to case complexity, directs a court to exclude time periods in respect of specific applications and requires that a stay of proceedings be ordered only if a court is satisfied, taking into account a list of factors, that no other remedy would be appropriate and just ….

and

create a new Division in respect of unreasonable delay that requires a court martial to consider specific factors in relation to case complexity, directs a court martial to exclude time periods in respect of specific applications and requires that a stay of proceedings be ordered only if a court martial is satisfied, taking into account a list of factors, that no other remedy would be appropriate and just ….

To quote Prince Hamlet, a procrastinator himself, this has the capacity to render the right to a speedy trial “more honoured in the breach than the observance” (1.4). The ongoing R. v. R.B.-C. deals with the question of unreasonable delay post-verdict in sentencing and whether to require an automatic stay of proceedings for breach. The Court is again asked to make determinations on matters of policy by upsetting well-established law from the 1987 case of R. v. Rahey which concluded that a stay of proceedings was the only appropriate and just remedy for a s. 11(b) violation.

While legislative efforts are welcome, the bill does not appear terribly nuanced or detailed with much scientific consideration that we would expect from Parliament, who is free to consult with experts. Rather, it looks drastically similar to the contextual framework from Morin. A more scientific approach would revisit the ceilings set out in Jordan with informed calculations of how long trials are actually taking. The correct approach would address the troubling rise of the population remanded in pre-trial custody without generating too many cases thrown out for delay. There is a congestion problem, but the appropriate framework must balance speedy trial interests with societal interest in deterring and punishing criminal activity. This complex issue belongs firmly in the domain of public policy rather than the courts.

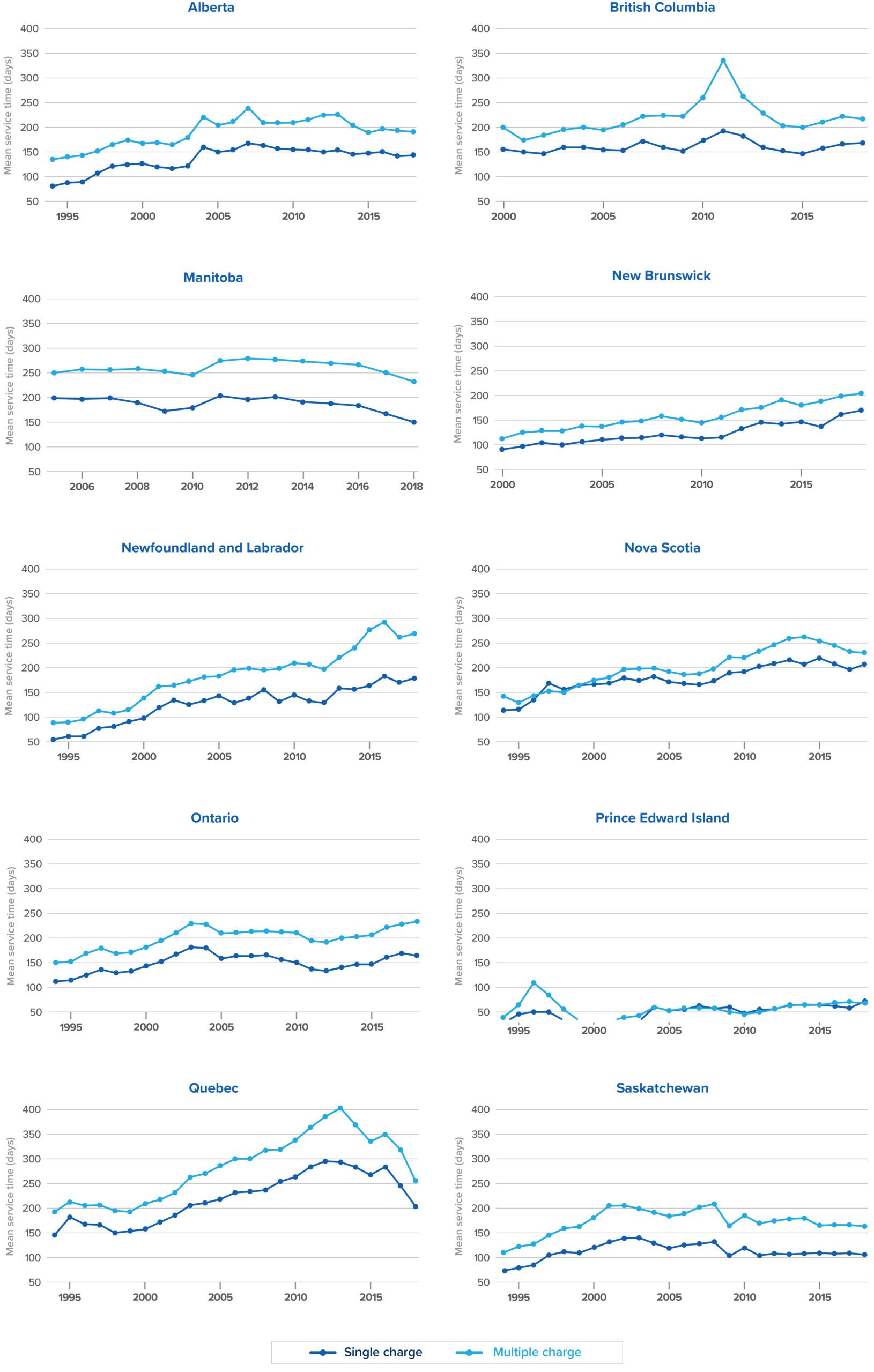

Figure 2 displays Clarke and Metzler’s average time from first appearance to final disposition across nine provinces by single- or multiple-charge cases.[1] The average time from first appearance to final disposition is close to around 200 days in most provinces in 2019, though the increasing trends in most provinces indicate that may change in the future. Based on the modelled distribution of trial durations, this implies that approximately one to six per cent of cases will exceed the Jordan ceiling of 18 or 30 months, or about 3,000 to 20,000 cases initiated each year depending on the percentage of cases that face the 18 or 30 month ceiling. This is close to what has been observed in reality.

Figure 2: Average time from first appearance to final disposition

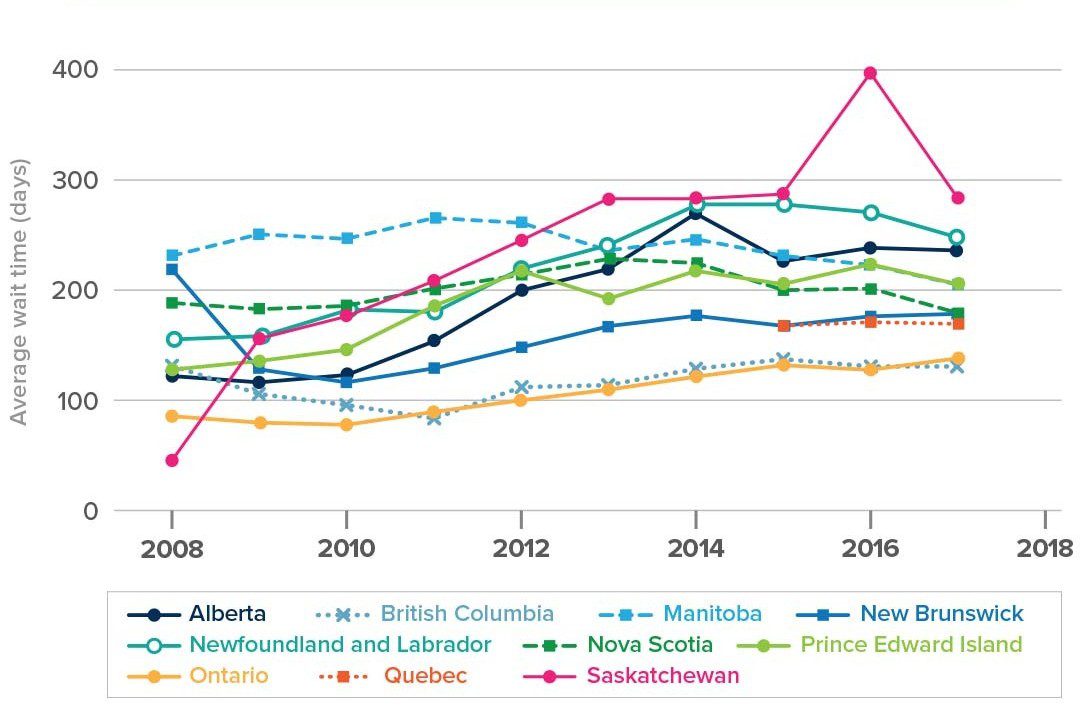

However, this does not include what Amsterdam calls the “pre-court phase” of trial, but only the “court phase” (Amsterdam 1975, p. 526), which is available in raw Statistics Canada data. Notably, Clarke and Metzler observe substantial variation across provinces in the implied average wait time that precedes it, which also considers the province’s caseload, suggesting that Jordan’s one-size-fits-all approach will have disparate impacts across provinces. Figure 3 displays the model-implied wait time as calculated by Clarke and Metzler using a workhorse queueing theory model.[2] Once variation in provincial caseloads is corrected for, substantial geographic variation arises in the total duration of the criminal trial, the sum of the pre-court and court phases. Trends indicate that courts are unable to manage their caseload under basic identities from queueing theory.

Figure 3: Model-Implied Average Time from Arrest to First Appearance

The principle of subsidiarity – that decisions should be made at the most local or least centralized level capable of addressing an issue effectively – suggests that these matters are best left to provincial legislatures or, with due care, by Parliament. While a single number may constitute presumptively unreasonable delay enshrined in the s. 11(b) right, that number will produce drastically different incentives and outcomes across the country. The wide variation across provinces – and even cities – calls for closer attention to which actors can constitutionally address local congestion and delay. As Justice Rowe reminded us in oral arguments during R. v. R.B.-C. “Canada doesn’t start in Scarborough and end in Mississauga.” The Court attempts to legislate this policy from the bench to encourage local actors to adjust their behaviour, but perhaps legislative efforts are better suited.

It is rather fitting that the Court used no data in the calculation of the Jordan ceilings, just as we might expect from an institution with insufficient competency on the matter. Justice Cromwell was correct in asserting that these matters are better left to fora that can tender a wide variety of expert evidence from different institutional actors and stakeholders.

Such future initiatives are welcome, but policymakers must dig deeper into the sea of available data on how to construct these ceilings, were that to be the correct approach. For example, certain crimes take substantially longer than others to reach a final result, and this may differ dramatically across provinces with different caseloads, creating an equilibrium where one-in-seven sexual assault trials was stayed or withdrawn in 2022–23. The separation of powers demands a new approach to the right to trial within reasonable time that confines the Court in its proper role in judicially reviewing acts of Parliament and not judicial policymaking.

Revisiting the law on the right to trial within reasonable time suggests several possible paths:

- Legislatively set ceilings drawn from consultation with experts;

- Ceilings that vary by offence and geography; and

- Clearly carved out exemptions rather than simple “rare and exceptional cases” (for example, national security or organized crime (Copeland and Chrustie 2025)).

The contrast between Jordan and the earlier Morin regime resembles the legal debate over rules versus standards. Jordan ceilings are a bright-line rule: clear, specific, and easy to apply. Meanwhile, Morin‘s contextual framework is a contextual standard. The typical rules versus standards theory applies: rules are cheap to enforce, but over- or under-inclusive with loopholes; standards are high in discretion and therefore subject to corruption; rules work well for frequent events, while standards are for rare, fact-specific events; rules offer clear guidance that can facilitate private ordering among actors.

The future of s. 11(b) must move beyond the rules-versus-standards debate by using data to create context-specific, algorithmically informed rules. One possibility is an actuarial table estimating trial length, with adjustments to determine what counts as an unreasonable trial delay in current circumstances. Radically reimagining the right to trial within a reasonable time cannot be left to the Supreme Court alone. If we fail to protect this relic of a right, tracing back to the Magna Carta, we risk losing it to policy reforms that undermine its effectiveness.

About the author

Dylan R. Clarke holds graduate degrees in law and economics and is currently a CUSP Fellow at the West Neighbourhood House. His research uses the tools of economics and statistics to study legal phenomena. His work has been published in the Journal of Urban Economics, Regional Science and Urban Economics, and the Journal of Law & Empirical Analysis.

References

Amsterdam, Anthony G. 1975. “Speedy Criminal Trial: Rights and Remedies.” Stanford Law Review 27:3 525–543.

Baar, Carl. 1997. “Court Delay Data as Social Science Evidence: The Supreme Court of Canada and ‘Trial Within a Reasonable Time.’” The Justice System Journal 19:2 123–144.

Clarke, Dylan, and Adam Metzler. 2025. “Estimating the Delay of Criminal Trials: Evidence from Canada.” Journal of Law & Empirical Analysis 2:1 33–59. Available at https://doi.org/10.1177/2755323X251341611.

Copeland, Peter, and Calvin Chrustie. 2025. “Modernize the legal system to confront 21st-century organized crime.” National Post, August 25. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/modernize-the-legal-system-to-confront-21st-century-organized-crime-peter-copeland-and-calvin-chrustie-in-the-national-post/.

David Ebner. 2025. “About 10,000 Jordan cases thrown out annually as Ottawa, provinces call on Supreme Court for change.” The Globe and Mail. Available at https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-jordan-cases-ottawa-provinces-supreme-court-change/.

Kalven Jr., Harry. 1963. “General Analysis of and Introduction to the Problem of Court Congestion and Delay, A Rules and Procedures.” American Bar Association, Section of Insurance, Negligence and Compensation Law. Proceedings 322.

Landes, William M. 1971. “An Economic Analysis of the Courts.” Journal of Law & Economics 61, 14:1.

Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime. 2023. Rethinking Justice for Survivors of Sexual Violence: A Systemic Investigation.

Barker v. Wingo, 407 U.S. 514 (1972)

R. v. Askov, [1990] 2 S.C.R. 1199

R. v. Charley, 2019 ONCA 726

R. v. Cody, 2017 SCC 31

R. v. Jordan, 2016 SCC 27

R. v. Morin, 1992 SCC 89

R. v. Rahey, [1987] 1 S.C.R. 588

[1] The mean is computed based on a maximum likelihood fit of the duration of trials according to an exponential distribution via a multinomial likelihood function for grouped data.

[2] The model-implied wait time is calculated as open caseload divided by cases initiated minus average time from first appearance to final disposition.