Indigenous communities rightfully view themselves as being more than just one more stakeholder group to consult in a long list of ticked boxes. They see themselves as full partners in the economy, and industry and government should pay attention to that new reality, writes Joseph Quesnel.

Indigenous communities rightfully view themselves as being more than just one more stakeholder group to consult in a long list of ticked boxes. They see themselves as full partners in the economy, and industry and government should pay attention to that new reality, writes Joseph Quesnel.

By Joseph Quesnel, January 31, 2018

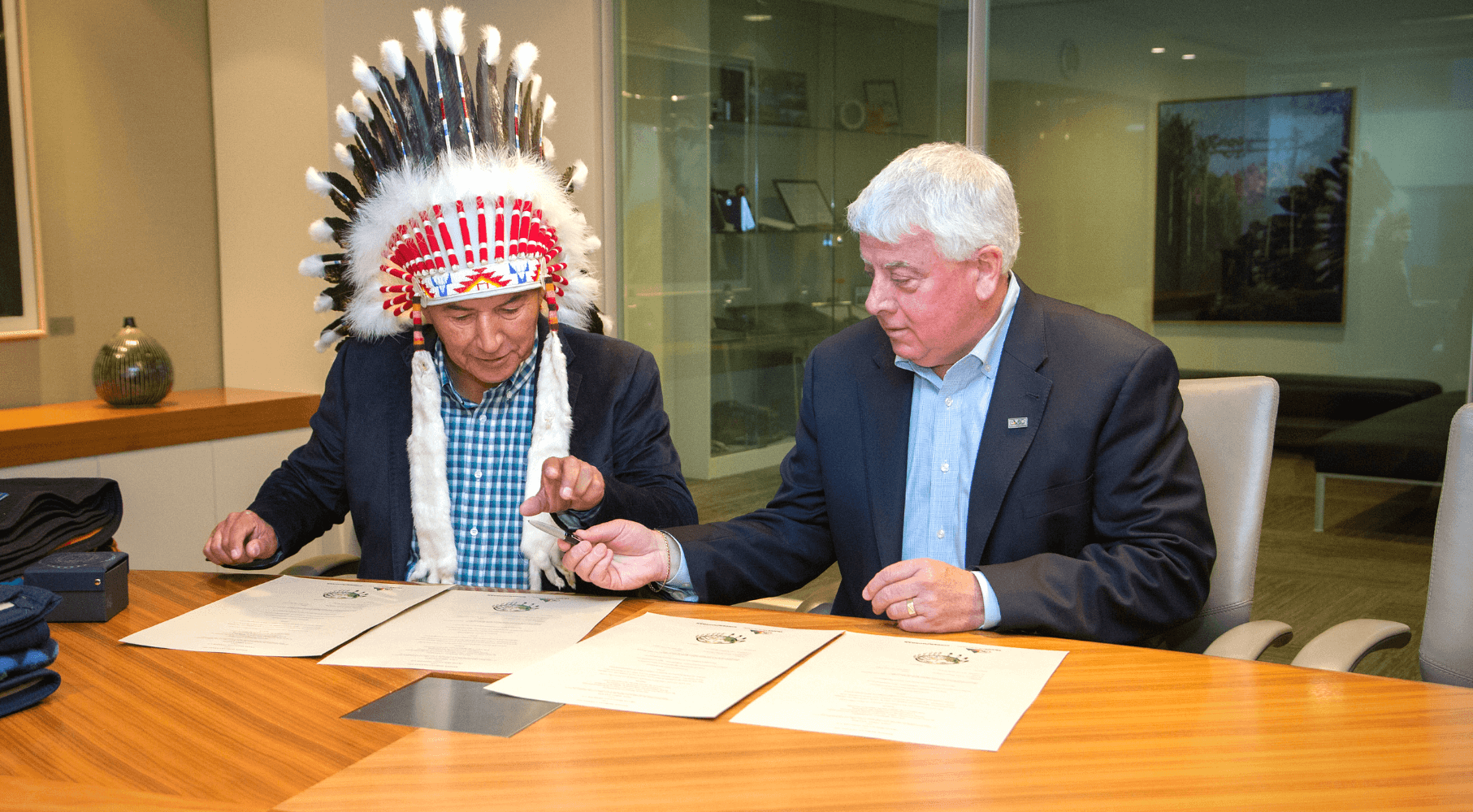

The desire of Indigenous groups to buy the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project should come as no surprise, especially to those who have been closely observing Indigenous resource investment for a while.

Indigenous communities over the past decade have become involved in big resource projects and partnerships that are turning them into major economic players in the sector. And they are set to play an ever-increasing role, as most resource projects that will be developed over the next decade are located on or close to First Nation traditional territories.

Governments in Canada should better facilitate and perhaps even incentivize First Nations to enter into partnerships with companies, especially at the level of equity partnership. The Crown is legally required to enter into collaboration with First Nations that find their rights and land title affected by resource development. Typically, this leads to an impact and benefit agreement. However, if Indigenous communities or partners secure equity participation in a resource project, they can secure long-term revenue sources. Some First Nations are dissatisfied with deals that only create short-term construction jobs that eventually disappear once the project is built; equity participation gives them a greater ability to control their own destiny through a stake in the company’s future success.

Indigenous communities are already breaking new ground on resource deals. For example, just recently, CN Rail and Wapahki Energy Ltd. – a company owned by the 250-member Heart Lake First Nation in northern Alberta – were in discussions on a joint venture plan to create a $50-million facility to process bitumen into solid pucks by mixing it with recycled plastic. The pucks could be loaded onto rail cars, trucks or shipping containers and would float on water, making them safer to transport by sea. Some recent technology observers predicted the pucks could someday reduce the need for oil pipelines.

To take another example, an Indigenous community in Saskatchewan is planning a $3-billion potash mine on their reserve – which would make it the first ever mine built on a reserve. Toronto-based Encanto Potash Corp. signed a deal back in 2010 with Muskowekwan First Nation (a small Indigenous community located 140 kilometres northeast of Regina) to develop the project.

In 2017, the federal government passed a law under the First Nations Commercial and Industrial Development Act (FNCIDA) that applies provincial mining regulations on the project lands involved. This harmonization of rules for federal reserve lands with provincial regulations helps create better economic certainty for investors. Most recently, Encanto launched a strategic plan to have the project shovel-ready in the next few years.

Another project is the 1,500 km-Eagle Spirit Pipeline, which brought together 35 First Nations to ship oil from northern Alberta to Prince Rupert, B.C. The plan was widely seen as a more environmentally friendly and safer alternative to the Trans Mountain expansion and the Northern Gateway. The project is currently threatened by the government’s tanker ban and delays associated with the National Energy Board (NEB) approval process.

Indigenous communities rightfully view themselves as being more than just one more stakeholder group to consult in a long list of ticked boxes. They see themselves as full partners in the economy, and industry and government should pay attention to that new reality.

Indigenous communities are also working and developing projects together. Government and industry need to show faith in them through their support to better facilitate Indigenous access to capital so that these communities can assemble the necessary funds when a deal comes around. There are already public and private institutions helping them to access capital, but there is much more work to do.

Federal politicians preparing platforms for the coming election, are you listening?

Joseph Quesnel is program manager for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Aboriginal Canada and the Natural Resource Economy project.