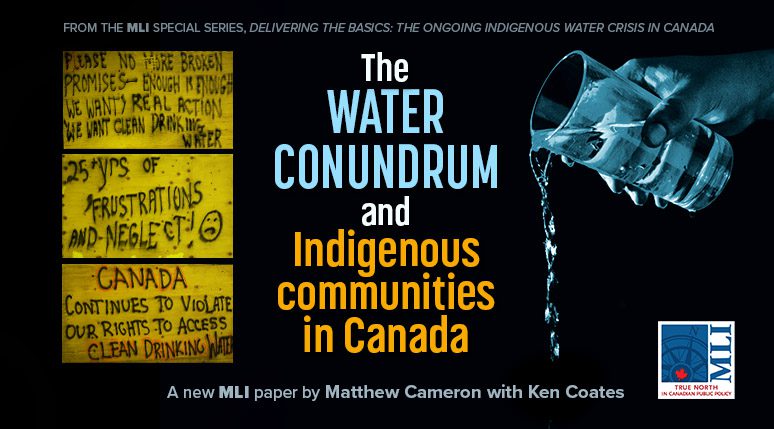

By Matthew Cameron and Ken Coates

November 22, 2023

Executive Summary

Most Canadians take safe, clean drinking water for granted – most, but not all. In fact, over 17,600 people in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario alone are currently living under a drinking water advisory that has been in place for longer than a year. These Canadians, the vast majority of whom live in First Nations communities, rely on bottled water for hydration, cooking and personal hygiene.

These communities go without access to clean water for years at a time despite the fact that Canada as a whole is incredibly well-endowed with clean, fresh and safe water; being home to 20 per cent of the world’s fresh water and seven per cent of its renewable water supply (despite making up less than 0.5 per cent of its population). How can this abundance be reconciled with the country’s inability to provide so many First Nations communities with secure access to one of the necessities of life?

This report finds that a variety of political decisions refracted through multiple levels of government, coupled with a host of geographical, logistical and informational challenges, have made providing consistent access to clean drinking water one of the most persistent and troubling problems in Canada, particularly in First Nations communities.

The federal government has devoted considerable resources into tackling this issue over the past two decades, investing more than $10 billion in water infrastructure for First Nations communities. Yet this spending has not been sufficient to fully eradicate the problem.

As of May 2023, there were officially a total of 31 long-term drinking water advisories in effect in Canada, impacting 27 Indigenous communities. This figure, however, does not capture the full scope of the problem as it excludes those public water systems that the federal government has not given funding to; nor does it account for long-term advisories in the territories. A full accounting, taking in these omissions from the official numbers, brings the current total across Canada to at least 55. Beyond the fragmentation of current figures, the lack of clear, consistent, and transparent data collection regarding long-term drinking water advisories, both historic and contemporary, makes it nearly impossible to get a clear picture of the extent of the problem within Canada.

The status quo is unacceptable as a lack of consistent access to safe drinking water is linked to myriad physical, mental, and emotional health issues, many far from obvious. In extreme cases, water insecurity has been linked to suicides in First Nations communities.

This report recommends that policymakers consider a number of policy initiatives to foster better outcomes. This includes implementing measures to enhance transparency, including publicizing information about delivery systems and down-times in water treatment facilities. Policymakers may also consider creating region-wide water management systems, which would allow for a sharing of personnel, nearby professional backup, and collective learning about water systems maintenance and treatment facilities (i.e., a maintenance economy of scale). They should also give greater attention to remote solutions and, in the most dire of circumstances, give affected populations the option to relocate to areas with safer water supplies. Finally, its imperative that policymakers adopt an increased sense of urgency in systematically addressing the problem, not just throwing money at it.