This article originally appeared in the Globe and Mail.

By Ken Coates, June 23, 2023

The $10-billion settlement announced this week between the Robinson-Huron First Nations, Ontario and the federal government signals a tectonic shift in Indigenous-government relations that extends far beyond the large sum awarded in this specific case.

The financial settlement, compensating First Nations in northern Ontario for more than a century of being denied a just portion of revenues generated by development on traditional lands, is a major precedent that will be useful to Indigenous peoples in western Canada.

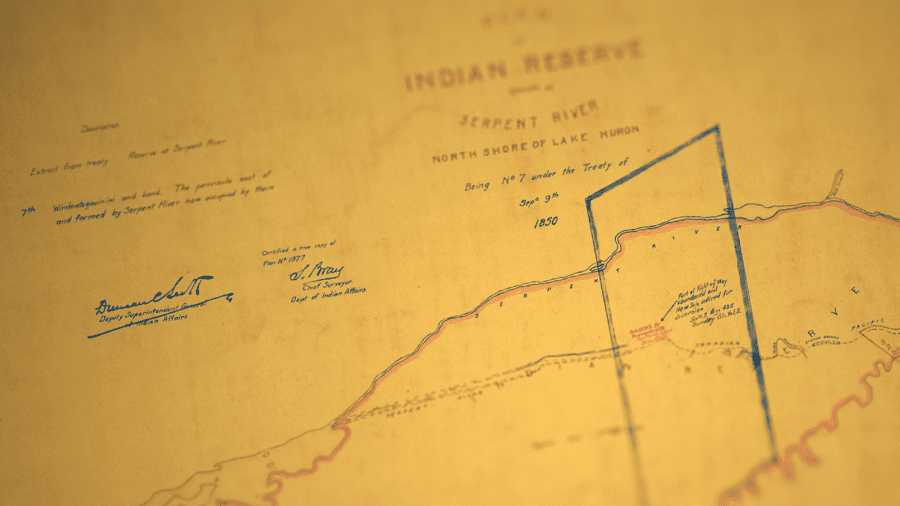

In 1850, the original Robinson Treaties, Huron and Superior, stated that if governments ever made money off the lands and resources around Lakes Huron and Superior, the First Nations would share in the bounty.

The small initial annuity was less than $2 per First Nations member. In 1874 it increased to $4, and has not changed since. Whenever First Nations demanded greater annuities, they were stonewalled by successive governments, even as the region experienced tremendous growth, seeing populations expand along with forestry operations, mining, tourism, road construction and energy projects.

More recently, First Nations signatories to the treaties sued the federal and Ontario governments for a fairer share of the wealth generated over the past 173 years, and in 2018 the courts agreed that additional compensation was due, but without settling on a final sum.

Responsibility for paying the $10-billion – an amount said to address historical grievances – will be divided between Ontario and Canada. The allocation will be shared, in ways yet to be determined by First Nations, between payments to individuals and community investment funds.

This resolution is long overdue. First Nations languished in long-term poverty while governments collected revenues from development of treaty lands. More should have been done to resolve this issue without the long, confrontational and expensive legal proceedings. However valuable the money is in the 2020s, it will never benefit those who were denied this justice over the last century and a half.

Meanwhile, negotiations continue, because while the settlement resolves First Nations’ claims going back to 1850, it does not establish compensation amounts going forward. But, as agreed in the original treaties, First Nations will receive payments tied to the use and development of the lands and resources in the treaty areas. This will, for the first time outside the modern treaty processes in the Canadian North, give First Nations an economic stake in the long-term economic prosperity of Ontario and Canada.

For Ontario, the settlement brings the provincial government to the table in a big way. Major developments of the Ring of Fire mineral properties and other northern Ontario projects are slowed by the absence of agreements with First Nations. A new prosperity-sharing formula will be critical in breaking future logjams.

Nationally, the significance of this agreement cannot be underestimated. Indigenous peoples deserve to be part of the development of their traditional territories. First Nations, Métis and Inuit groups have long held that federal and provincial governments ignore their right to benefit financially from land use and resource developments.

When Canada purchased Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1870, the federal government reserved for itself the lands and resources in the area. Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta became provinces without the same property jurisdiction that underpinned provincial economies in the rest of the country.

In 1930, Ottawa transferred land and resources to the three Prairie provinces through the Natural Resources Transfer Acts (NRTA). The West’s heavy financial dependence on resource development can be largely traced to this rejigging of provincial authority. First Nations were not consulted (in the 1930s, the lack of attention to Indigenous concerns was all-pervasive) and no arrangements were made to share revenues or commercial opportunities with Indigenous peoples.

First Nations have repeatedly threatened to take the federal government to court over the NRTA. The claim is legally untested and therefore casts uncertainty over Indigenous affairs and resource development in the West. For western First Nations, the Robinson treaty settlement – which focuses on the lack of attention to the spirit of the 1850 treaties – will stiffen the resolve of First Nations and strengthen their legal and political arguments.

Canada continues to pay the price for generations of neglecting treaty and Indigenous rights. Failing to recognize First Nations, Métis and Inuit aspirations slows development, perpetuates inequalities and is a constant reminder of Canada’s failure to deal honourably with Indigenous peoples.

Basic national self-interest, as well as moral and legal obligations to Indigenous peoples, speaks to the need for Canada and the provinces to quickly and fairly address unresolved Indigenous rights and claims. The 2023 settlement of the Robinson-Huron case is a major step in the right direction.

Ken Coates is a distinguished fellow and director of Indigenous Policy Program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.