This article originally appeared in the National Post.

This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Jack Mintz, October 5, 2022

Unlike interest rates or the weather, long-run demographic trends are highly predictable. Today, we are facing a demographic storm that will have far-reaching impacts on the economy and geopolitics.

Labour markets will be tight for years to come, which will fuel inflation. With falling national saving rates, the saving glut and low real interest rates that have spurred investment will disappear. Like Japan in recent years, GDP growth will stall in many high- and middle-income countries, as more people leave the workforce. Unless productivity remarkably improves, annual GDP growth will fall below 1.5 per cent in many large countries, half the typical post-Second World War rate of three per cent.

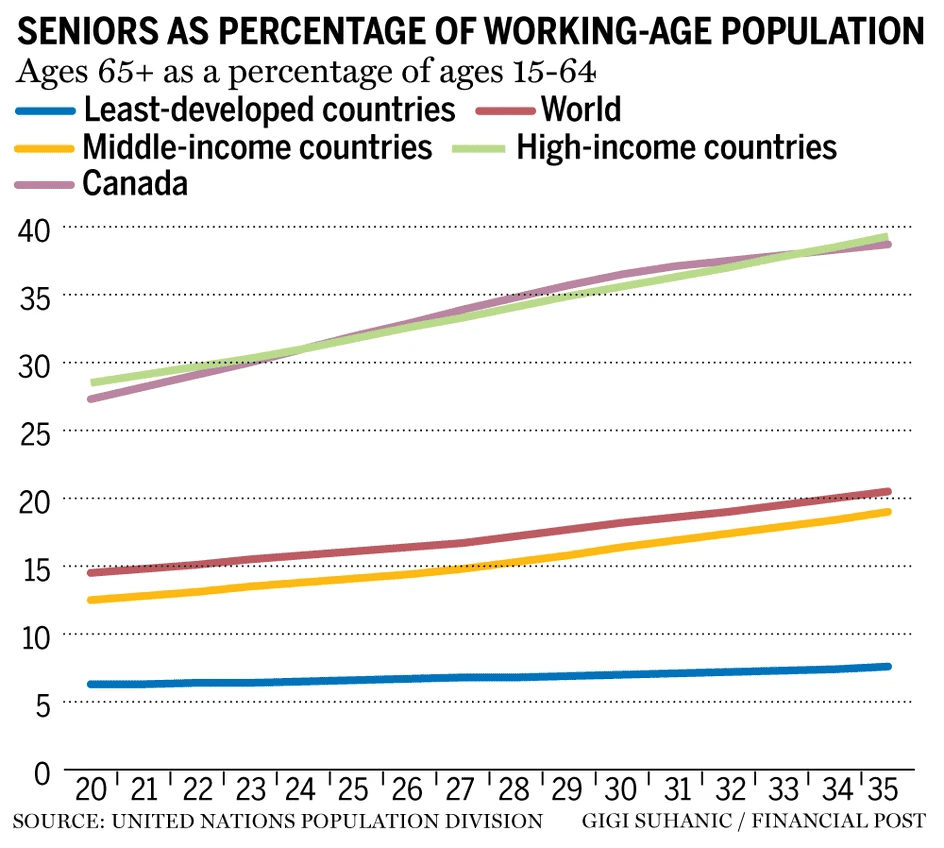

Rapid population aging is happening in North America, Europe, China, Brazil and many other countries. As shown in the accompanying graph, aging is a phenomenon everywhere except in the least-developed economies. The United Nations projects that by 2035, the global population over 65, as a percentage of the working age population (ages 15-64), will increase to 20.5 per cent, from 14.5 per cent in 2020. The number of dependants, in other words, will increase substantially, and the problem will be even more acute in high-income countries.

Over the past 50 years, we have seen a huge growth in the global labour supply, driven by baby boomers and women entering the workforce. Many Asian countries, especially China, with their massive workforces, liberalized their economies and became more integrated in global markets. With falling transportation and communications costs, it was feasible to shift production to low-wage countries that, in turn, suppressed wages in industrialized economies. This trend will change, however, as stalled labour growth in high- and middle-income countries pushes up real wages, which will be good news for many workers.

As seniors grow as a share of the world population, some countries will experience a labour boom as their numerous young people enter the workforce. Age dependency — young people (one-15 years old) and seniors (over 65) as a percentage of the population between 15 and 64 years of age — will drop dramatically in the least-developed economies: from 75 per cent in 2020, to 66 per cent in 2035, contrary to trends in the rest of the world. Falling age dependency will keep wages from rising in underdeveloped economies, but it also means that the income inequality between rich and poor countries will widen.

High-income countries will witness their elderly selling off their assets to support their retirement, which means that national saving rates will fall. This will be further aggravated by the recent growth in public deficits. Ultimately, increased investment demands due to defence needs, the energy transition and industrial investment to reduce labour expenses will absorb the current saving glut and raise real interest rates, which has already started to happen.

Canada’s workforce is also rapidly aging. By 2035, there will be five working Canadians for every two retirees. People are living longer, but they are also ill for longer periods with diseases like dementia. Many low-income Canadians will not have sufficient resources to cover their living costs, putting pressure on governments to provide more subsidized health care, long-term care and pension support. Meanwhile, the working population will begrudge seniors for leaving them with a bellyful of public debt, high housing prices and more taxes, which will almost certainly become an issue at the ballot box.

Some high-income countries will bring in more workers from abroad to improve population growth, to the detriment of their own workers, who would otherwise benefit from higher wages. It will also lead to a reversal of economic aid as rich countries scoop up the best and brightest from poor countries. Regardless, recruitment, especially of skilled workers, won’t be easy as international labour markets become tighter.

In 2007, before the financial crisis, four million people migrated to Europe, Oceania and North America, primarily from Asia, the Caribbean and Latin America. That has steadily dropped, to 2.3 million today. Fewer Chinese people are migrating to other countries, dropping from over 439,000 in 2007 to 200,000 in 2021. Likewise, fewer migrants are moving to G7 countries — net migration fell from 2.7 million in 2007, to 1.4 million in 2021. While this may change as the world further recovers from the pandemic, rising incomes, especially in middle-income countries, will reduce the incentive for citizens to leave home.

Even with a stalled labour force, per capita incomes can grow with productivity gains due to innovation and education. Yet this decade will be a challenging one for productivity. Political conflict — as seen with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, trade frictions and the energy transition — will disrupt economies over the coming decade. Highly indebted countries with weak institutions will be especially hard pressed by rising inflation and interest rates, leading to a collapse in their exchange rates, as happened in Turkey recently. Political turmoil has already taken shape in Sri Lanka and the Netherlands, after the governments adopted fertilizer restrictions, leading to a precipitous decline in agriculture production. In the Czech Republic, 70,000 people recently took to the streets, calling on their governments to take more action against inflation.

If migration and productivity gains are hard to come by, governments could improve growth by encouraging more labour force participation. Early childhood education and accessible childcare would free up some parents to work. Last year, Japan raised its retirement age for pensions from 65 to 70, and is reducing retirement benefits for people between 60 and 64 years of age. Reducing high marginal effective tax rates as a result of personal income taxes and income-tested benefits, which was discussed recently by Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, would also encourage more labour force participation, since people would not pay as much personal taxes or lose income-tested benefits.

Population aging over the next decade is very predictable; less predictable will be the public policy response to the eventual labour market and fiscal pressures that evolve from it.

Jack Mintz is the President’s Fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy and Distinguished Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.